News • Environmental disease driver

Study links air pollution to increased risk of ALS

Prolonged exposure to air pollution can be linked to an elevated risk for serious neurodegenerative diseases like ALS and seems to speed up the pathological process, report researchers from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden.

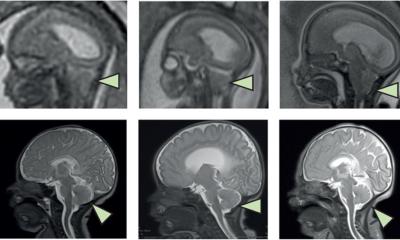

Image source: Karolinska Institutet; photo: Yuqi Zhang

The study is published in the journal JAMA Neurology.

“We can see a clear association, despite the fact that levels of air pollution in Sweden are lower than in many other countries,” says Jing Wu, researcher at the Institute of Environmental Medicine, Karolinska Institutet. “This underlines the importance of improving air quality.”

Motor neuron diseases (MNDs) are serious neurological diseases in which the nerve cells that govern voluntary movement become so degraded that they stop working, leading to muscle atrophy and paralysis. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) is the most common type, accounting for around 85% to 90% of cases.

The causes of these diseases are largely unknown, but environmental factors have long been suspected of playing a part. The new study shows that air pollution can be one such factor.

The study included 1,463 participants in Sweden with recently diagnosed MND, who were compared with 1,768 siblings and over 7,000 matched controls from the general population. The researchers analysed levels of particles (PM2.5, PM2.5-10, PM10) and nitrogen dioxide at their home addresses up to ten years prior to their diagnoses. The annual mean values for these pollutants were just above the WHO guidelines and the peak values were much lower than in countries with heavy air pollution.

Image source: Karolinska Institutet; photo: Andreas Andersson

Long-term exposure to air pollution, even at relatively low levels typical of Sweden, was associated with a 20% to 30% higher risk of developing MND. Moreover, people who had lived in areas with higher levels of air pollution experienced more rapid motor and pulmonary deterioration after diagnosis. They also had an elevated risk of death and were more likely to need treatment in an invasive ventilator.

“Our results suggest that air pollution might not only contribute to the onset of the disease, but also affect how quickly it progresses,” says Caroline Ingre, adjunct professor at the Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet.

When confining their analyses to ALS patients, the researchers found virtually the same pattern as for the entire MND group.

The researchers stress that the study is unable to show the mechanisms behind the association, but previous research indicates that air pollution can cause inflammation and oxidative stress in the nervous system. Since it was an observational study, no causal relationship can be ascertained.

The study was based on Swedish registry data and was financed by several bodies, including the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the Swedish Research Council and Karolinska Institutet. Some of the authors have received research grants and/or fees from pharmaceutical companies; see the article for a full conflict of interest declaration.

Source: Karolinska Institutet

21.01.2026