Screening

AB-MRI could be the ideal screening tool

MRI is increasingly relevant to cancer management, especially to detect breast carcinoma. Professor Christiane K Kuhl from the department of diagnostic and interventional radiology at the University of Aachen, Germany, strongly advocated in favour of MRI in breast cancer screening during a dedicated Satellite Symposium organised by Bracco at ECR 2015.

Report: Mélisande Rouger

‘If one thing has been proven by screening mammography, it is that early diagnosis of a malignant disease does indeed translate into improved survival. This concept justifies the use of screening in general and specifically for breast cancer. We have indeed seen a decrease of mortality rates over the past decades,’ said radiologist Professor Christiane Kuhl, opening her presentation during a Satellite Symposium at this year’s ECR.

However, regardless of the benefits, a number of issues still call for improved cancer screening methods. Mammographic screening, just like PSA screening for prostate cancer, may pick possibly irrelevant diseases, which even if left undiagnosed would never progress to an actual life-threatening condition.

Early publications on over-diagnosis through mammographic screening claimed that one out of three breast cancers represented over-diagnosis. However, it is currently, and probably more realistically, estimated that about 10% of breast cancers do belong to that group, Kuhl pointed out.

Mammography in fact has technology-inherent bias to detect slowly growing cancers. ‘What we really pick are calcifications and architectural distortions. So triple negative breast cancers, which grow rapidly and don’t calcify, are likely to go unnoticed by mammography,’ she explained. The detection of breast cancer through mammography depicts pathophysiological changes that reflect regressive changes such as hypoxia, necrosis, fibrosis, calcification and architectural distortions.

Another challenge with mammography is under-diagnosis. ‘Surprisingly enough, this is not discussed so much by the scientific community, although it’s clear that mammography screening has a limited sensitivity for prognostically relevant disease,’ she pointed out. Despite decades of studying breast cancer in epidemiologic studies, it continues to be the leading cause of cancer death in women and the most common cause of death in women under 50. ‘Over-diagnosis is not our main problem. If it were, no one would die. Both over and under-diagnosis are shortcomings of mammographic screenings,’ she said.

Other screening candidates have been studied, starting with digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT). A study that was conducted in over 400,000 women and published last year in JAMA showed that DBT presented with a 30% increase in detection rate compared with mammography alone. Another side effect was an improved PPV, in other words a higher specificity in distinguishing pathology alterations and benign changes.

In 2008 another study, also published in JAMA, compared the use of hand-held ultrasound with mammography and found an additional cancer yield of 4.1 per thousand. Acquisition time, on the other hand, was considerable, as it took over 20 minutes to complete a bilateral screening examination. Two years later, the authors published an update, in which they compared a single round of screening MRI with mammography. They found a 14.6 per thousand additional cancer yields with MRI.

Kuhl is a strong advocate for MRI in breast cancer screening. Fifteen years ago, she and her team published the very first paper on the topic, in which they highlighted MRI’s high sensitivity and specificity. Their updated results, in 2005 and 2010, reported the exact same data. Moreover, the EVA trial, which was conducted in four different sites in Germany, confirmed that MRI had higher sensitivity than ultrasound or mammography in women at increased risk of breast cancer.

Interestingly, other publications that reported lower sensitivity of MRI compared with mammography found opposite results a few years later, stressing the importance of the user’s experience with MRI, Kuhl explained. ‘This evolution curve is represented in many studies. If you see variable results for MRI for screening use, this usually reflects a learning curve that radiology or the radiological community has to take in every area, not only for breast MRI but also possibly for prostate MRI.’

Kuhl also set out to tackle critics about MRI’s supposedly high false positive rates in her presentation. ‘MRI has often been reported to offer low specificity, which is certainly not true. Again, that is something that can be avoided with experience. More recent multi-centre trials, such as the EVA trial, showed that MRI had higher specificity than mammography,’ she confirmed.

MRI can also be used as a screening tool for women at average risk. In an upcoming paper, Kuhl will show that, in those women, MRI has a 20 per thousand detection rate and an acceptably high PPV.

Finding more cancers with MRI should not be a problem, the researcher believes: ‘More diagnosis is not more over-diagnosis, because, even today, too many women die of breast cancer. We still have a problem. We don´t have to detect all the cancers but we should detect the ones that kill.’

The main issue facing MRI today is that economic considerations are driving its use for screening. One reason for high costs is the fact that the same (extensive) pulse sequence protocols have been used for breast MRI screening as the ones that have been used for diagnostic purposes.

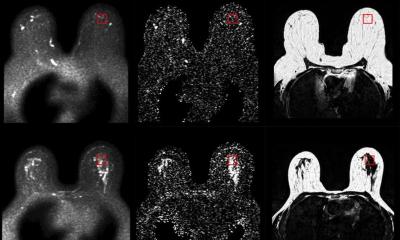

To make breast MRI a real screening tool, Kuhl introduced the concept of abbreviated breast MRI (AB-MRI). ‘AB-MRI means to strip down the pulse sequence protocol to its very essence,’ she explained.

Her corresponding study (pub: Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2014) used such an abbreviated protocol, which consisted of one pre- and one post-contrast acquisition, equaling a magnet time of about three minutes. Conducted between 2009 and 2010, the study compared the diagnostic accuracy and cancer yield of this abbreviated protocol against that full breast imaging protocol. Kuhl found that this was sufficient to help diagnose the same number of additional cancers, with similar diagnostic accuracy. Moreover, she found that the radiologists reading time of just three seconds was enough to exclude the presence of breast cancer with a negative predictive value of just under 99%. ‘Establishing absence of breast cancer on a negative MIP image is done in the blink of an eye,’ she said, ‘and, in a screening setting, the vast majority of women have no cancer. By comparison, for a negative screening ultrasound study, a radiologist needs to work for 20 minutes.’

Accordingly, AB-MRI actually has the potential to make breast MRI a real screening tool, she argued. ‘AB-MRI offers an additional cancer yield of 18.3 per thousand in women who have been pre-screened by digital full-field mammography and physician-performed breast ultrasound. It may be the ideal screening tool for women because it is conceivable to conduct on a population-wide scale, has high sensitivity for biologically relevant cancers and high diagnostic accuracy – and there’s no radiation involved.”

Kuhl pointed out that, just like prostate MRI, breast MRI is relatively blind for low-grade disease, especially low-grade DCIS. ‘Replacing mammography by breast MRI, rather than adding MRI to mammography, may therefore be the way to proceed,’ she said.

Radiologists must understand that the aim of breast cancer screening is not to detect all breast cancers and their precursors by all means, she insisted. ‘Rather, the goal must be to develop imaging methods that combine a maximum sensitivity for prognostically relevant disease with a desirable lack of sensitivity for disease that is prognostically unimportant.’

06.03.2015