Slovak's private radiology institute

First came state-of-the-art equipment, then patients. Now, says Peter Bor×uta, patience is also needed, before perhaps the chance to carry out research becomes a reality. Peter Boruta MD PhD is Professor of Radiology and Head of Radiology at Slovak Medical University, in Bratislava, and Director of the Diagnostic Imaging Institute in Trnava.

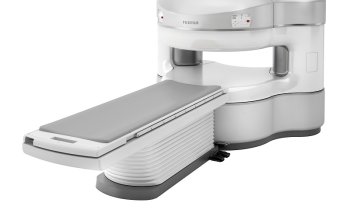

When, a few years ago he was approached to establish a state-of-the-art radiology institute in a polyclinic next to Trnava’s university hospital, he and his partner travelled to Germany to observe private radiology clinics there. Two years ago they installed MRI equipment at Trnava. ‘After that we introduced mammography, then ultrasound, CT and conventional X-ray with computerised radiology. So now Trnava can provide complete imaging diagnostics. In addition, we train radiologists, radiographers, and nurses to work in radiology.’

Funding for the new institute came from a Slovakian bank. ‘We were the fifth to want an MRI unit – the first was in Banska, which had been effective, so the bank was interested. However, it was a hard battle because the bank knew nothing about me or my partner. We supplied our details – my partner is strong on money and I’m a little better on X-ray. They tried a contract with us; we proved we were not so bad, then the bank gave us better conditions, so then came the rest of our equipment.’

In Czechoslovakia the Trnava Institute is the first to have a 64-slice CT scanner. It also has 22 trained personnel, eight of whom are radiologists – because the open MRI system is slower than high magnetic machines, so three physicians are needed for the magnet and the institute also runs two shifts, Dr Boruta explained. ‘We are up and running, but completely new in this region, so as yet we have few patients.’

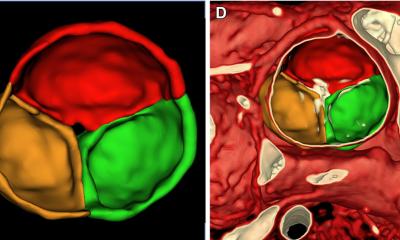

After his first job (six years) focusing on cardio-radiology in a children’s hospital, Dr Bor×uta became the first radiologist to use Brataslava’s CT scanner. ‘I worked with that old axial scanner for a long time, so I’m certified to combine CT and cardiology.’

Asked how changes in eastern Europe impacted on his work, Dr Boruta reflected it has not been easy to change one political system for another. ‘After our border opened many radiologists went to Czech or western countries – most to England, where pay is ten times higher compared with the USA. I must pay my radiologists more than in the US. We work so hard that they can have better pay and they have more interest because I don’t just give them money, but also the chance to work with the most sophisticated equipment and to do complex diagnoses. So when an insurer has a problem about where to send a patient, we explain that, for angiography, MRI is better than conventional angiography. Also, I’m lucky because radiologists have to come to me for training, so I give the okay if they are excellent and work hard. So I ask whether they want hard work, with excellent equipment and better pay and most say yes. If they work in England they get more pay, but must spend more – and not everyone wants to be in England.’

However, foreign work and training has its benefits. Trnava personnel have trained in hospitals in other countries, among them one in Copenhagen, where they worked on Toshiba’s 64-slice. Also, years ago, Dr Boruta trained in Freiberg and Heidelberg. Continuing contact with those colleagues resulted in the formation of a German-Slovak Academic Radiology Association. ‘We established it during further training in Heidelberg, to exchange new information about our work, new teachings and modalities and what we are using in oncology – for example, the 64 slice scanner.’ In addition the association agreed that the Institute’s physicians and medical students can receive training in Heidelberg.

Research

When the first CT scanner was installed in the bio-medical research institute in Bratislava, because the institute was next to the hospital, close cooperation resulted and Dr Bor×uta participated in research. ‘In our CT department we particularly worked closely with neurosurgeons on stereotactic techniques. From 1983–86 the main problem was artifacts in the fixed ring. We worked with the Slovakian Academic Institute and had ideas about special stereotactic amperages from Stockholm and Germany, but it was too expensive and our technicians didn’t have special stereotactic equipment. A Philips representative came to Bratislava and was immediately interested, so Philips began to cooperate with us. However, due to a cross-border communications problem, we had to end this. Two years before the Eastern Block changed, the two mathematicians on the programme went to Freiberg to see Vilmar Fisher, who was making stereotactic equipment, about collaboration. They worked in Freiberg for five years. They now work in our oncology institute, where they don’t use a gamma knife, but the accelerator with stereotactic equipment to treat arrhythmias and tumours. We did the research.’

Dr Boruta’s desire to encourage and participate in more research is evident. ‘It is part of our philosophy that medical care also needs university research. We have the qualified personnel, equipment and a large number of patients. We can do research. But I must find funds.’ This presents a big stumbling block. Sponsors are easier to find in the West, he suggests, though he believes, for eastern European countries, improvements are on the way.

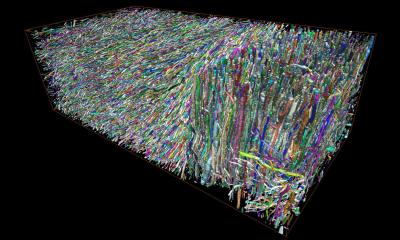

He wants the institute’s research to not only focus on cardiovascular imaging, but also on lung imaging, using the 64-slice CT scanner as well as X-ray and MRI. The Slovak Academic Institute is also interested in MRI for lungs, and the combination also interests large groups from Western countries, he said. Other European countries, wanting to coordinate research to improve care in new European countries, might bring hope in terms of funds. Among meetings to that effect, one discussion has led to ‘quite a lot of money’ now going to eastern countries, he pointed out. However, he said, with regret, that the partners’ workload has been too heavy to submit any requests, and although EU representatives had visited, and a lot of paperwork had been submitted, funding did not result. ‘You read that in other countries they have a problem finding funds. It all takes time – five to ten years, maybe less,’ he reasoned.

Research in Eastern countries, he pointed out, is currently at a basic level, due to lack of funding. For now, he added, raising money to buy necessary equipment has been and must be the partners’ basic work. ‘We started with the CT scanner in July. Up to December I had a hell of a problem to get the money for the work I did.’ And lenders, he stressed, must be paid every month.

Could private patients present a good source of income? In Slovakia, less than one percent of patients are private, he replied, so the insurers pay for 99.9% of patients at his private radiology institute. But, he added, with some puzzlement, the institute has received one female cardiac patient, from Vienna. ‘In Austria, insurers don’t pay for CT examinations, which is a general problem in Europe,’ he explained. In conclusion, he said with a smile: ‘In Trnava I must sum up every day whether we have worked well. One bad case and you lose your credentials. So you take no chances, you give quality, and must be patient, because there are also good and bad doctors out there. I only provide a service. I’d be stupid if I told a doctor You are stupid. Why did you send me this patient? No, I will thank him for sending that patient to me.’

01.05.2007