Mysterious Actinium

Short-Lived Isotope Provides New Possibilities for Cancer Treatment

A recent paper published in Nature Communications reveals insights about the element actinium that could support new classes of anticancer drugs. The experiment was conducted by the Department of Energy's Los Alamos National Laboratory in collaboration with the DOE's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

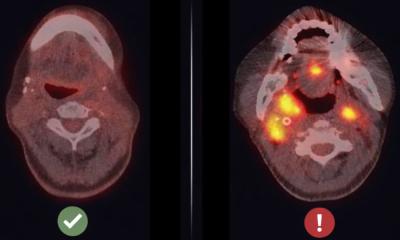

An isotope of actinium, actinium-225, has a relatively short half-life (10 days) and emits powerful alpha particles as it decays to stable bismuth. This makes it a perfect candidate for a novel cancer treatment technique called targeted alpha therapy, where alpha emissions from radioisotopes destroy malignant cells while minimizing the damage to healthy surrounding tissue.

However, this can only become a reliable cancer treatment if actinium securely binds to what’s known as a chelator, or targeting molecule, as the radioisotope is very toxic to healthy tissue if it is not brought quickly to the site of disease.

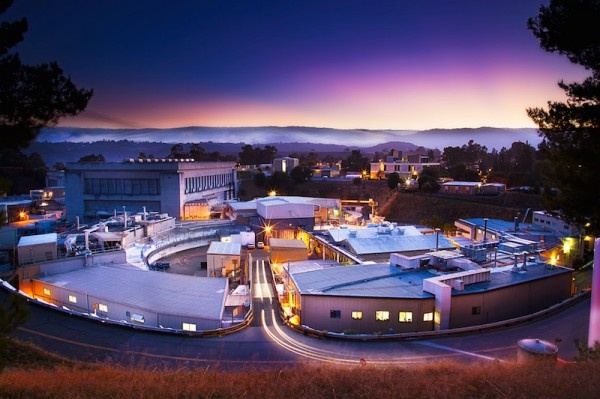

The new study demonstrates that unique capabilities at SLAC's Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) – a DOE Office of Science User Facility – provide an opportunity to characterize the molecular and electronic structure, including chemical bonds in compounds containing highly radioactive elements, like actinium, using only trace amounts. This manuscript represents the first in a series of studies that focus on providing needed chemical information for researchers to develop ways to safely transport actinium-225 through the body to tumor cells.

“To build an appropriate biological delivery system for actinium, there is a clear need to better establish the chemical fundamentals for actinium,” says Maryline Ferrier, a researcher on the Los Alamos team and lead author on the paper. “Using only a few micrograms (approximately the weight of one grain of sand) we were able to study actinium-containing compounds at SSRL and at Los Alamos, and to study actinium in various environments to understand its behavior in solution.” The researchers exploited SSRL instrumentation designed primarily for environmental science to conduct the first actinium X-ray absorption fine structure study reported to date.

The actinide chemistry group at Los Alamos used data from a new detector at SSRL to determine information about chemical bonds formed by actinium, including what binds to the element – in this case, oxygen or chlorine – how many atoms are present, and the distances between them.

Before this study, most of the known chemical data for actinium was collected during the Manhattan Project. And aside from a few measurements on actinium powders, no other structural data was available. “Imagine if someone gave you the element iron and nothing was known. That’s almost the same place we were in with actinium, as far as macroscopic chemistry goes,” says Stosh Kozimor, an isotope chemist at Los Alamos and co-author on the paper.

Actinium is too radioactive to be able to characterize using conventional methods, Kozimor says. The Manhattan Project scientists used film to see the X-rays released off the sample. But the radioactivity from actinium darkened the film before they could make meaningful measurements. “They were only able to get a fingerprint of the actinium compounds that were suggestive of what formed. Beyond that, there isn’t much information in those measurements,” Kozimor says. “It’s because we haven’t had the spectroscopic tools to characterize actinium compounds, and now at SSRL we do.”

In ongoing and future studies, the researchers will use similar methods to look at how actinium binds with a chelator and attempt to engineer the carrier molecule specifically for actinium.

Source: SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

06.09.2016