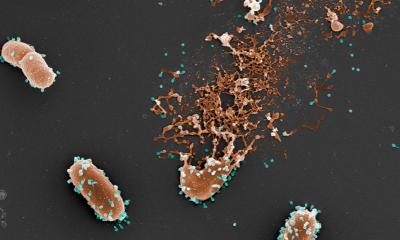

Photograph: ETH Zürich / Stefan Fattinger

News • Microbiology

Resistance can spread without antibiotics use

Antibiotic resistance does not spread only where and when antibiotics are used in large quantities, ETH researchers conclude from laboratory experiments.

Bacteria are becoming increasingly resistant to common antibiotics. Often, resistance is mediated by resistance genes, which can simply jump from one bacterial population to the next. It’s a common assumption that the resistance genes spread primarily when antibiotics are used, a rationale backed up by Darwin’s theory: only in cases where antibiotics are actually being used does a resistant bacterium have an advantage over other bacteria. In an antibiotic-free environment, resistant bacteria have no advantage. This explains why health experts are concerned about the excessive use of antibiotics and call for more restrictions on their use.

Recommended article

Article • Fighting infections

‘We are sitting on a ticking time bomb’

Multidrug-resistant organisms (MDRO) are keeping infection specialists worldwide on their toes. One of these specialists travelled all the way from Leipzig to India to gain insights in one of the sources of the problem.

However, a team of researchers led by scientists from ETH Zurich and the University of Basel have now discovered an additional, previously unknown mechanism that spreads resistance in intestinal bacteria that is independent of the use of antibiotics. “Restricting the use of antibiotics is important and the indeed the right thing to do, but this measure alone is not sufficient to prevent the spread of resistance,” says Médéric Diard, who until recently held a post at ETH Zurich and is now a professor at the Biozentrum of the University of Basel. He continues, “If you want to control the spread of resistance genes, you have to start with the resistant microorganisms themselves and prevent these from spreading through, say, more effective hygiene measures or vaccinations.” Diard led the research project together with Wolf-Dietrich Hardt, Professor for Microbiology at ETH Zurich.

Recommended article

Article • Measles

Vaccine hesitancy threatens global health

Globally, a trend of falling public trust in vaccines is alarming health officials and the World Health Organisation (WHO) lists vaccine hesitancy as one of the top 10 threats to global health. The UK’s Wellcome Trust 2018 Global Monitor – a survey of more than 140,000 people in over 140 countries – highlighted regions where confidence in vaccinations is lowest.

Persisters: Dangerous 'sleepers'

Persistent bacteria, also known as persisters, are responsible for this newly discovered resistance-spreading mechanism. Scientists have known for some time that, just like bacteria that carry resistance genes, persisters can survive antibiotic treatment. They fall into a temporary, dormant state and can reduce their metabolism to a minimum, which prevents the antibiotics from killing them. In the case of salmonella, the bacteria become dormant when they penetrate the body tissue from inside the gut. Once they have invaded the tissue, the persisters can live there undetected for months before awakening from their dormant state. If the conditions are conducive to bacterial survival, the infection can flare up again.

Even if the persisters don’t cause a new infection, they can still have an adverse effect. In salmonella, a combination of the two resistance mechanisms is common: persisters that also carry small DNA molecules (plasmids) containing resistance genes.

By exploiting their persistent host bacterium, the resistance plasmids can survive for a prolonged period in one host before transferring into other bacteria. This speeds up their spread

Wolf-Dietrich Hardt

In experiments with mice, the researchers demonstrated that dormant salmonella in the gut can pass their resistance genes on to other individual bacteria of the same species and even to other species, such as E. coli from the normal intestinal flora. Their experiments showed that persisters are very efficient at sharing their resistance genes as soon as they awaken from their dormant state and encounter other bacteria that are susceptible to gene transfer. “By exploiting their persistent host bacterium, the resistance plasmids can survive for a prolonged period in one host before transferring into other bacteria. This speeds up their spread,” ETH professor Hardt explains. It’s important to note here that this transfer happens regardless of whether antibiotics are present or not.

The researchers now want to take their findings in mice and explore these more closely in livestock that frequently suffer from salmonella infections, such as pigs. The scientists also want to investigate whether it’s possible to control the spread of resistance in livestock populations with probiotics or with a vaccination against salmonella.

Source: ETH Zurich

05.09.2019