Image source: Adobe Stock/pangoasis

Article • Disaster victim identification

Radiology in DVI: distressing insights and “hidden gems”

Identifying victims of major disasters remains a significant challenge for investigators. Often, identification can take weeks or longer but new approaches are paving the way for greater accuracy and quicker identification whilst preserving the body without unnecessary invasive investigation.

Report: Mark Nicholls

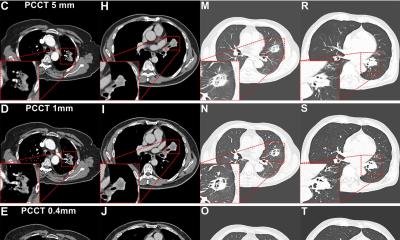

In mass casualties or terrorist attacks, many victims need to be identified despite the possible extensive destruction of the bodies. Radiology has become essential in this process. More recently, greater use of 3D reconstruction which is harnessing CT to add a non-invasive dimension to disaster victim identification (DVI) to unlock some of the challenges of DVI.

A session dedicated to DVI at ECR 2023 in Vienna heard how 3D imaging technology is building up pictures of victims and re-assembling body parts – often while the remains are still in the body bag – while also conducting investigations in a way that preserves the dignity of the victim. In turn, that offers reassurance to relatives that the investigation is being conducted in a humane and sympathetic manner.

Forensic pathologist Dr Mike Biggs, from the East Midlands Forensic Pathology Unit in Leicester in the UK, has been involved in a range of high-profile investigations. These included the MH17 incident (with the UK nationals involved); Shoreham Airshow crash; and the Grenfell Tower fire in London (where mobile CT scanning was used).

Bringing together what belongs together

The anatomy is not always in the right place and with fragmented bodies it can take time to work out what is going on. This is where the 3D application can be very helpful

Mike Biggs

In cases where coroners specifically request non-invasive investigations, 3D imaging offers benefits. Biggs suggests there are ‘hidden gems’ of information contained in the DICOM data but that accessing it can at times be problematic, particularly where mobile scanners are used. ‘You can answer specific questions if you are willing to extract data from DICOM,’ he said. The 3D application has value in reconciliation of body parts, that may even be in different bags. ‘The anatomy is not always in the right place and with fragmented bodies it can take time to work out what is going on. This is where the 3D application can be very helpful,’ said Biggs.

He outlined how CT scanning of body bags can identify victims from distinctive jewellery or clothing and then start answering specific questions, with reliance on comparison of ante-mortem and post-mortem data to reach an identification.

The standard Interpol approach for DVI body reconciliation was outlined to delegates, with pink post-mortem paperwork and yellow ante-mortem data (fingerprints, dental records, DNA samples) following scene investigation to bring the elements together to obtain a positive identification.

In addition, pathologists are increasingly being asked by police to produce physical 3D prints for the courtroom, particularly when coroners want scan-only autopsies rather than invasive examinations. Biggs said the 3D software can clean-up images, removing vegetation, degradation, and insects, and produce sanitised colour images that are less distressing for jurors.

Powerful reconstruction and analysis possibilities

With fragmented bodies, the available tools can produce inventories of the bones that are present and absent, arrange them in presentation form, and reassemble them.

The expert recalled one example, where there were no dental records, and the individual was identified from a Facebook profile picture, with the help of a 3D print of the teeth which matched the victim. In another case, with a fragmented skull of an unidentified person, the technology reassembled the skull to create a facial reconstruction and use that to put out an appeal for witnesses.

It is also possible to show the way the force propagated through a bone to identify what happened to cause a fracture. ‘There is the potential for doing very useful analysis,’ he added.

Preserving the integrity of the body

In introducing the session, radiographer and co-chair Mark Viner said DVI sat within the congress theme of “The Cycle of Life” and the medico-legal process of identifying the person who died ‘so loved ones can grieve and begin the healing process.’ This, he said, can be complex, particularly in mass fatality incidents with trauma, body fragmentation or decomposition and where reliance is on the hard tissues of bone and teeth that survive long after the soft tissues have gone.

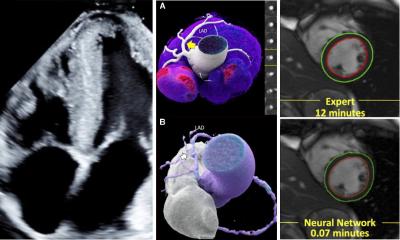

Radiology was first proposed for human identification as early as 1896 and first used in a mass fatality incident in 1949, with the non-invasive tool of CT coming to the fore more recently. ‘This means we can we use technology to answer question of identity less invasively, preserving the integrity of the body for the loved ones. In recent years, mobile multidetector CT (MDCT) has become the gold standard for DVI investigations,’ said Viner.

Shift from x-ray to CT imaging

The session also heard from Dr Arne Stray-Pedersen from Oslo, Norway, who discussed the role of radiology on victims of the 2011 terror attacks in Norway with a bomb explosion followed by mass shootings at a youth camp.

Thomas Ruder from Berne, Switzerland, meanwhile discussed the use of radiology in DVI, highlighting how whole-body CT in a post-mortem setting makes all structures of the body available to compare to ante-mortem images. ‘The use of radiology for identification and DVI has seen a transition from x-ray to post-mortem CT, as we have seen in the clinical side of radiology. CT is much more versatile for identification.’ The scenario and the conditions of an incident determine imaging modalities and roles as a biological and medical profile is established. ‘Comparative radiologic identification is based on visual pattern recognition, which also plays a central role in clinical radiology,’ said Ruder.

Profiles:

Dr Thomas Ruder is a Consultant Radiologist at the University Hospital in Bern, Switzerland, and Associate Editor of the journal Forensic Imaging.

Dr Mark Viner has wide experience as a radiographer, radiology manager and NHS senior manager and is a senior tutor in dental and maxillofacial radiography at Queen Mary University of London and senior lecturer in forensic radiography at Cranfield University, Shrivenham.

03.08.2023