Article • He who seeks, finds

Pros and cons of MRI in breast cancer diagnosis

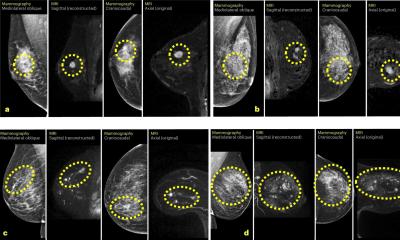

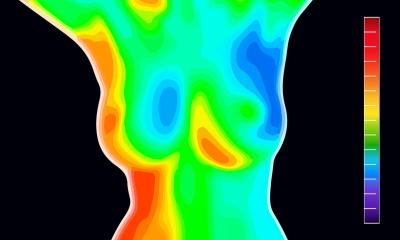

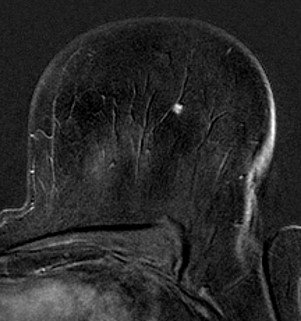

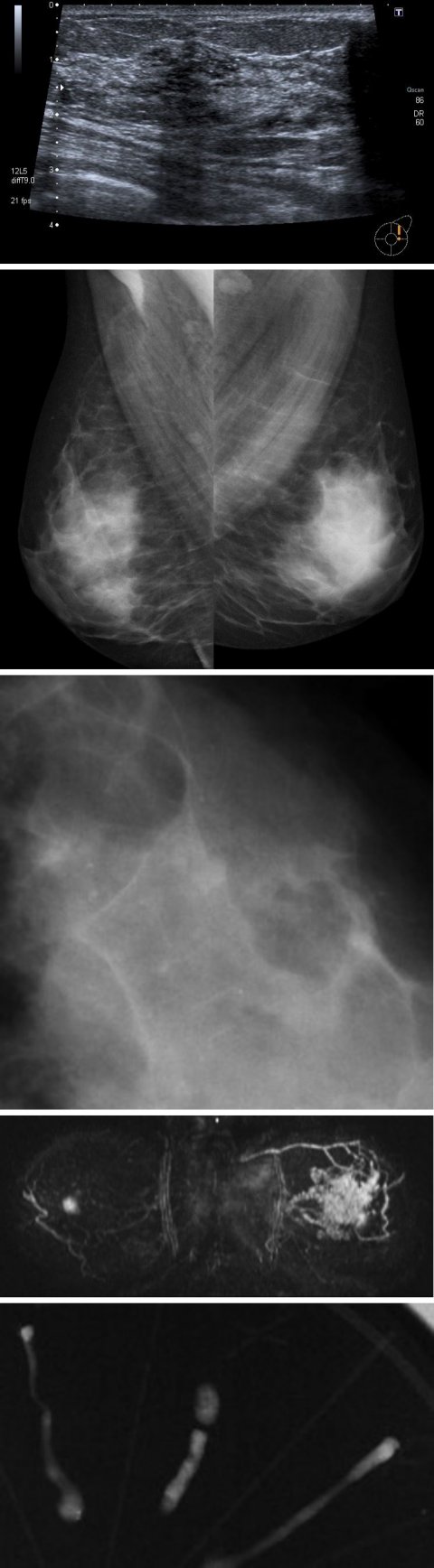

MRI is the most sensitive method to detect breast cancer. However, the current breast cancer guidelines for Europe, Germany and Austria, still only recommend it for certain indications: For early detection in high risk patients, for differentiation between scarring and recurrences after breast-conserving treatment and to detect cancers of unknown primary site. This is the theory.

Report: Karoline Laarmann

However, in practice potential MRI applications are being discussed more controversially. At this year’s Röko Congress, Professor Ulrich Bick, head of Breast Cancer Diagnostics at the Charité in Berlin, spoke about the indications for contrast-enhanced breast MRI.

Problems begin with the identification of those at particular risk, explains the expert explained. ‘The main issue is the determination of the individual risk of developing the disease. There are healthy women who are carriers of a high-risk gene, such as a mutation of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene, for whom the intensive, early diagnosis with MRI is the only sensible alternative to prophylactic surgery. It becomes more difficult for those who are either at moderate genetic risk or not at genetic risk but at known familial risk. The question is, where do you set the threshold for individual risk which necessitates more intensive monitoring?’

Detection rate depends on risk constellation and age

A 10-year study by the German Consortium for Familial Breast-and Ovarian Cancer documents to what extent the selection of the risk group is important in breast MRI. The positive predictive value of a conspicuous screening MRI in high risk patients under the age of 40 and without genetic mutations, for instance, was only 2.8%. ‘This means that breast cancer in this age group is so rare that only one in 30 results will turn out to be malignant, with all other conspicuous MRI results turning out to be benign changes which do not need treatment. ‘In this case, MRI unfortunately leads to large numbers of false positive results which can cause real worry for young women who are not suffering from cancer,’ Bick pointed out. The second problem with early detection via MRI is the danger of overdiagnosis in older women, i.e. the discovery of slow growing, clinically irrelevant cancers. Due to its high sensitivity, breast MRI not only detects aggressive but also many slow growing cancers of low malignancy. ‘With breast cancer screening it’s not actually the modality used which is decisive for the types of tumour we find, but the patient’s genetic predisposition.’ This also applies to triple-negative breast cancer which occurs particularly frequently in those with the BRCA1 mutation: ‘This type of cancer is so aggressive that chemotherapy is often required even when the tumour is detected via MRI scan at an early stage.’

MRI in general breast screening

Bick does not perceive MRI as a standalone solution for breast cancer screening programs of the general population. ‘For this to be beneficial and to find fast-growing cancers, we would have to carry out MRI screening every 1.5 – 2 years. This would be too much for those at normal risk. After all, you don’t put on a second seatbelt in a car, either.’ However, the radiologist criticises the limited availability of MRI to clarify unclear results from mammography screening. ‘It would be an excellent indication for a clear answer as to whether cancer is present or not,’ Bick pointed out.

He views the situation around MRI-guided biopsy, which has not yet been included in the list of procedures covered by statutory medical insurers, in a similar way: ‘If the MRI shows something which no other method can visualise then carrying out a biopsy with MRI guidance should also be covered. Unfortunately, the MDK has so far rejected the procedure as being too experimental. It is clear, however, that if there was an agreed renumeration code in the system, the procedure would be carried out.’

MRI in the preoperative setting

The use of MRI for preoperative staging is particularly controversial. The main point of criticism is that the procedure can lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment. Its significance has already been examined in numerous randomised studies. The latest data presented from the international MIPA study suggests that preoperative MRI does not improve patient outcome. However, Bick believes it is less the MRI diagnosis than the patient’s and the surgeon’s personal preferences that are decisive for the surgical approach. ‘Some try to conserve as much tissue as possible and accept that they may have to operate again. Others are more generous with their resection and will obviously not need to operate again. A study to control all these factors would be almost impossible to carry out.’

The guidelines recommend preoperative staging with MRI only in some individual cases, and preferably suggest it for lobular breast cancer. ‘Further indications are large tumours where the issue is whether or not breast-conserving surgery is feasible or whether a mastectomy is needed,’ Bick added, ‘or young patients where we frequently detect additional, high-risk lesions. Basically, it’s the same situation as with screening. If the probability of finding cancer is high, the use of MRI makes sense.’

Profile:

Prof. Ulrich Bick is Vice Chairman of the Department of Radiology at the Charité in Berlin, where he works and researches, and this is one of 22 German centres for Familial Breast and Ovarian Cancer. The radiologist was awarded the Felix-Wachsmann-Prize by the DRG in 2006. He has been a member of the board at the German Society for Senology since 2013. He also shares particularly interesting clinical breast imaging cases on Instagram @mammoquiz

19.01.2021