Interview • Neurological diseases

No case for a psychiatrist’s couch

Up to ten years ago only a handful of antibodies that could be detected in the blood were known to neurology.

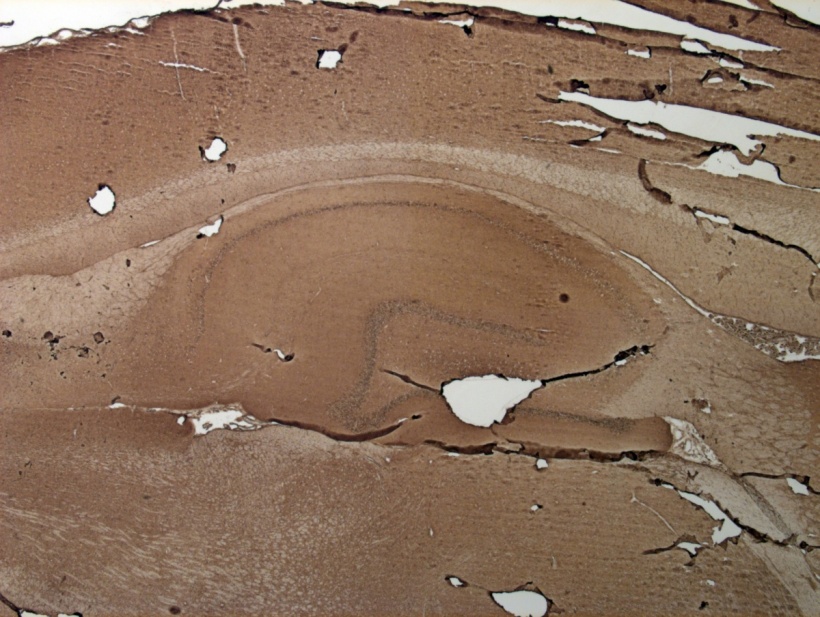

Patients had inflammatory changes in the brain or spinal cord and also malignant tumours. When an antibody was detected this automatically triggered the search for a tumour. Usually, patients’ neurological symptoms improved once the tumour was removed. In 2005, the Catalan neurologist Dr Josep Dalmau, working at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, was the first researcher to describe new antibodies found in liquor from young women suffering encephalitis, but not necessarily also from uncontrolled tissue growth. This was the starting signal for the discovery of new antibodies, a process that is still not complete.

In Germany the Institute for Clinical Chemistry at the University Hospital Schleswig Holstein is pursuing the diagnosis of, and research into, these antibodies. In our European Hospital interview with Professor Klaus-Peter Wandinger and PD Dr Frank Leypoldt, neurologists and trained/trainee laboratory medics, we asked how Dalmau discovered the new antibodies.

Wandinger: ‘Professor Dalmau carried out research in the field of neuro-oncology in the US for a long time and collected and examined a lot of liquor and serum. He found N-Methyl-D-Aspartate-Receptor (NMDAR) antibodies in around 100 patients, who all had similar clinical symptoms and responded to immunosuppressive treatment. These were mainly young women aged between 20 and 40, who initially displayed psychiatric symptoms.

‘The clinical picture usually started with the patients hearing voices or experiencing hallucinations, similar to schizophrenia. They then also suffered from epileptic fits, which were so severe that their breathing was affected to such an extent that they had to be treated in intensive care. It was a severe clinical picture, which was life threatening in around 20% of patients but which, up to that point, could not be diagnosed.’

What are NMDAR antibodies and how do they trigger these symptoms?

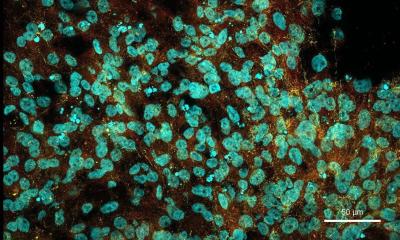

Leypoldt: The NMDAR antibodies are a subspecies of glutamate receptors. Glutamate is a messenger substance in the brain that transmits impulses from receptor to receptor. The antibodies that normally fight foreign cells in the body for reasons still unknown, bind to the NMDA receptors and block the transmission by the messenger substance. Communication between the nerve cells is impaired, which leads to psychiatric and neurological symptoms.

‘In Dalmau’s study, up to 40% of patients, amongst them many female Afro-Americans, had ovarian teratoma i.e. a benign ovarian tumour; in a German study cohort of patients, 25% were affected. As germ cell tumours also develop nerve cells it’s assumed that these trigger the autoimmune reaction against the NMDA receptor.

What happens when the anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis is not diagnosed in time?

Wandinger: ‘This is a real problem. We are currently raising awareness of this through the German Network for Research on Autoimmune Encephalitis (GENERATE). In the worst instance, such as the case of a child in Northern Germany, encephalitis is diagnosed through an examination of the liquor, but the laboratory does not find any pathogens. Without the test for neuronal antibodies and the respective immunotherapy the patient’s condition did not improve and he was on the brink of being transferred to a facility for the disabled. It was only after a consultant in the rehabilitation clinic ordered an antibody examination that the patient received the appropriate help, and he is now able to lead an independent and self-sufficient life again.

‘Thankfully, many more neurologists are now aware of this disease and there are test systems used in laboratories worldwide for the detection of the antibodies. If no diagnosis is made the disease can also have a fatal outcome.’

What is the incidence of this disease?

Leypoldt: ‘It is a rare disease and we are trying to determine exact epidemiological data through the register of the national network. Current estimates stand at around one case per one million people a year. However, autoimmune encephalitis is more frequent than all types of encephalitides caused by pathogens such as Herpes Simplex Encephalitis.’

Which examinations do you perform at the institute?

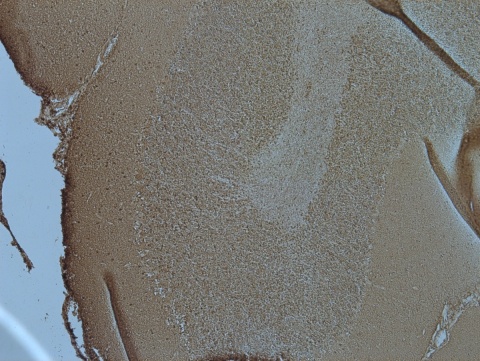

Wandinger: Over the last ten years a further 12 antibodies have been identified, many of those by Josep Dalmau, but also by Angela Vincent, in Oxford, who heads up the second largest working group on this topic. Neurologists can indicate a suspected anti-immune disease and also any clinical details on our test request form. We then use the procedures we’ve developed to test for the known neuronal antibodies, and also for antibodies as yet unknown, using further tests from our research laboratory that were developed in close cooperation with Professor Dalmau and which are not available to buy.

‘We not only do this for hospitals in all of the German speaking countries but we also work with laboratories in Spain, the USA and Australia. Our dual qualification is unique. I am already a qualified specialist for laboratory medicine and Dr Leypoldt will soon qualify. When a positive result is confirmed we are well qualified to advise doctors on treatment.

‘The clinical pictures of autoimmune diseases are not that well known outside of centres for maximum care, and colleagues are grateful for our guidance.’

Might more antibodies be discovered?

Leypoldt: ‘It is to be assumed that more will be found as there is a vast number of potential target proteins within the nervous system. Theoretically, each protein can trigger an auto immune reaction in the body, especially when it’s located on the cell surfaces where antibodies have good access. Some people most probably have a genetic predisposition.

‘For now, the large groups, the most common autoantibodies, have been described with the laboratory procedures currently available. But the research continues for seronegative, i.e. antibody negative autoimmune encephalitides, for example. If no antibodies can be detected it doesn’t necessarily mean that they don’t exist.

‘One of Dalmau’s most important findings was the development of new laboratory procedures that can be used to identify a whole group of diseases through defined antibodies, i.e. patients who we had previously only perceived as suffering from encephalitis.

‘There are biomarkers for specific groups of diseases that are very similar and treatable. Following this advance into new dimensions it is likely that further steps will be made to identify and treat diseases not yet classified.’

Profiles:

Following medical studies at the University of Lübeck Professor Klaus-Peter Wandinger MD became a researcher in the Neuroimmunology Department at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) in Bethesda/USA. In 2000 he became a researcher under Professor Einhäupl in the Neurology Department at the Charité Clinic. Three years later he wrote his habilitation on a neuroimmunology topic. He was involved in the development of laboratory procedures at Euroimmun and, since 2013, has been Deputy Director of the Institute of Clinical Chemistry, Campus Lübeck, University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein (UKSH).

PD Dr Frank Leypoldt is currently training as a specialist in laboratory medicine at the Institute for Clinical Chemistry at UKSH. He also heads the neuroimmunological out-patient department at the UKSH Campus Kiel. A qualified neurologist, he gained his doctorate at the University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf, where he also completed a postgraduate course in molecular biology. He worked in Hamburg as a post-doc fellow and, between late 2012 and 2014, in Barcelona under Professor Josep Dalmau. He has been employed at the UKSH since 2014 and wrote his habilitation in 2015.

06.01.2017