Image credit: Anne Weston - Francis Crick Institute (via Wellcome Collection; CC BY-NC 4.0)

News • Potential treatments for relapsing breast cancer patients

New technique for tracking resistant breast cancer cells

Cambridge scientists have managed to identify and kill those breast cancer cells that evade standard treatments in a study in mice. The approach is a step towards the development of new treatments to prevent relapse in patients.

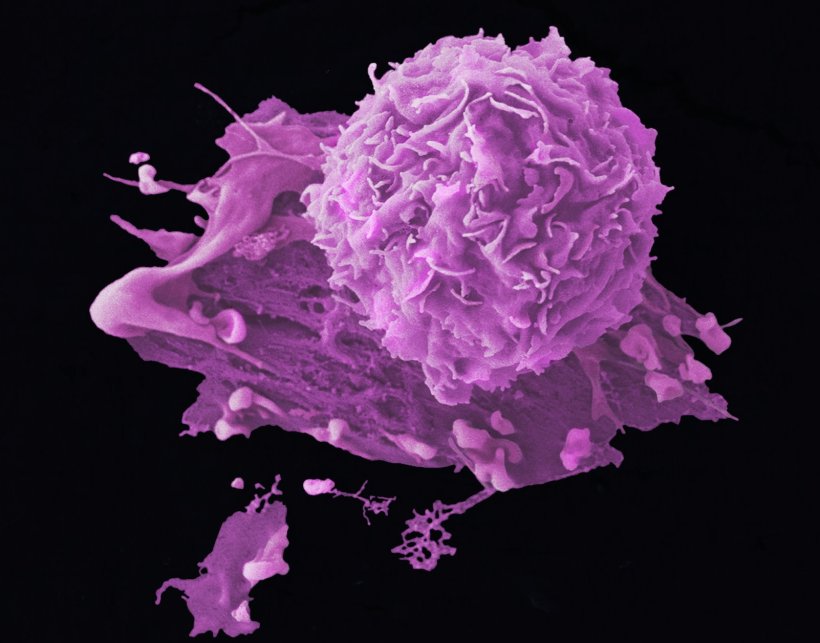

Tumours are complex entities made up of many types of cells, including cancer cells and normal cells. But even within a single tumour there are a diverse range of cancer cells – and this is one reason why standard therapies fail. When a tumour is treated with anti-cancer drugs, cancer cells that are susceptible to the drug die, the tumour shrinks and the therapy appears to be successful. But in reality, a small number of cancer cells in the tumour may be able to survive the treatment and regrow, often more persistently, causing a relapse.

In a study published in eLife, scientists from Professor Greg Hannon’s IMAXT lab at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute at the University of Cambridge have developed a new technique for identifying the different types of cells in a tumour. Their method – developed in mouse tumours – allows them to track the cells during treatment, seeing which types of cell die and which survive. The IMAXT team was previously awarded £20 million by Cancer Grand Challenges, funded by Cancer Research UK.

Until now, it hasn’t been possible to work out which these cells are and what makes them special, but our technique means that we can now do just that

Kirsty Sawicka

Dr Kirsty Sawicka from the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute said: “Tumours are incredibly complex, made up of many different types of tumour cells that have acquired genetic mutations as they evolve and replicate – and some of these cells are able to evade standard cancer treatments. Until now, it hasn’t been possible to work out which these cells are and what makes them special, but our technique means that we can now do just that.”

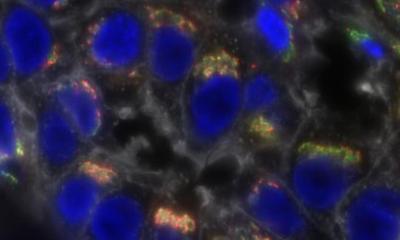

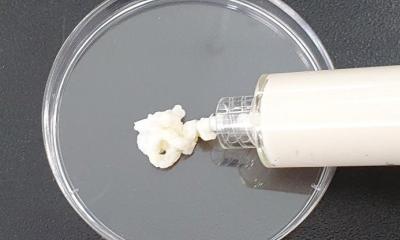

The team used viruses to tag different types of breast cancer cells with a unique genetic ‘barcode’. They then formed tumours from these cells in mice and treated them with the same drugs used to treat patients with breast cancer. By scanning the barcodes using recently developed single cell sequencing technologies – which look for those genes that are turned on or off in the cell – they were able to identify the different types of cancer cells, how many of those cells there are and what their characteristics are – and which types of cancer cells are not killed effectively by standard treatments. The team noticed that the cells that evade chemotherapy are those that have a greater reliance on asparagine, an amino acid that cells use to protect themselves from damage. By then administering L-asparaginase – a drug currently used to treat patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, which breaks down asparagine – they were able to specifically target and kill these tumour cells.

Dr Ian Cannell from the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute said: “Offering some kind of ‘combination therapy’ that adds asparaginase to the standard treatment could be a way of further shrinking tumours in breast cancer patients and reducing their risk of relapse. Although we see evidence that these evasive tumour cells are increased in patients after chemotherapy, so far, we’ve only shown that we can target them in mice, so there’s still a long way to go before it leads to a treatment for patients. Before we can do that we need to find the best way of administering the drugs – would we give the drugs together, for example, or offer the standard treatment and then asparaginase.”

Source: © University of Cambridge (CC BY 4.0)

21.12.2022