News • Usage for Covid-19 and beyond

'Microwaving' an ambulance could revolutionise surface disinfection

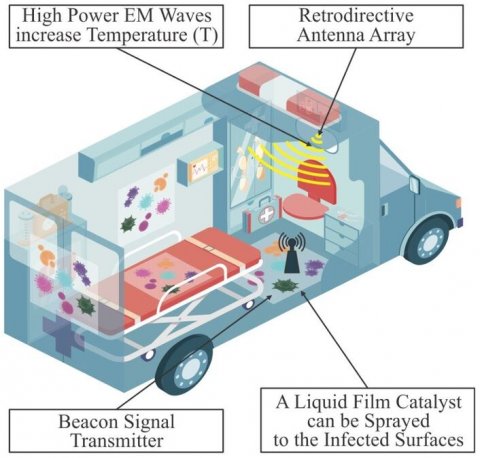

Microwave engineers, infectious disease specialists and polymer scientists from the University of Edinburgh, Heriot-Watt University and the University of Strathclyde have teamed up to create a novel microwave sterilisation method that could revolutionise the way ambulances and hospitals are being disinfected.

Image source: Heriot-Watt University

At present, sterilisation is done manually with conventional techniques that use chemicals. This can take around 30 to 40 minutes to disinfect a single ambulance. During this time, the ambulance is out of action which puts increasing pressure on emergency services during busy times. The possibility of the new technique could drastically reduce the time it takes to get an ambulance safely back on the road to save lives.

In recent years, several other techniques have been proposed for disinfecting and sterilising surfaces, ranging from hydrogen peroxide aerosols to UV irradiation and infrared radiation. However, these techniques have been shown to degrade surfaces over time, or to be harmful to humans if they are in close proximity. This has, so far, limited their long-term application. In contrast, the new method works using electromagnetic waves, antennas, sensor beacons, and a liquid layer to rapidly heat-up and sterilise surfaces. Its automation means a person can easily operate the system from a safe distance rather than touching contaminated surfaces directly during cleaning.

Published in the IEEE Journal of Electromagnetics, RF and Microwaves in Medicine and Biology, the study used microwave beams emanating from antennas like those found in mobile smart phones and domestic Wi-Fi systems. The antennas allow the microwave radiation to be directed and focussed on locations where it is most needed.

Recommended article

Article • Covid-19 disinfection

New insights into SARS-CoV-2 surface stability and temperature susceptibility

Surface disinfection has proved an effective method to control Covid-19 infection, as virologists from the Ruhr University Bochum (RUB) have shown. However, an effective disinfection strategy against Coronavirus must consider various factors, says Professor Eike Steinmann, head of the Department of Molecular and Medical Virology at the RUB.

The Scottish team was led Dr Symon Podilchak, professional engineer and a senior lecturer of radio frequency technology from the University of Edinburgh and an honorary associate professor at Heriot-Watt University. He explained: “I got the idea over a year ago when sterilising baby bottles for my newborn son using a microwave oven. It was when the Covid-19 pandemic was just starting in the UK in early 2020. I realised that if bottles could be sterilised in just a few minutes and were safe for a newborn child then it was possible to scale the technique for infected surfaces. However, significant research was required to determine the relative distance between the surface and the antenna whilst ensuring safe power levels. I also figured out that it would be better to target and focus the microwave beam to the areas most likely to be affected. To do this, I reused a technique that I originally developed for charging mobile phones wirelessly.”

The beauty of this new technique is that the surfaces sterilised are not being degraded which was one of the key challenges found with using UV light or aerosol techniques

Marc Desmulliez

Podilchak then connected with Professor Marc Desmulliez, a chartered engineer and physicist from Heriot-Watt University who previously developed a microwave powered, open-ended oven. This device was shown to enable the deactivation of live coronavirus (strain 229E) at a relatively low temperature of 60°C in 30 seconds. This latter part of the research was carried out in collaboration with a group led by Professor Juergen Haas, an expert in Infection Medicine at the Edinburgh Medical School.

Professor Marc Desmulliez from Heriot-Watt University said: “The beauty of this new technique is that the surfaces sterilised are not being degraded which was one of the key challenges found with using UV light or aerosol techniques. The resulting microwave device can also be portable, and this means it can be applied in multiple other applications beyond ambulances and operating theatres. It could be used to sterilise dinner tables in restaurants or clean train or airplane tables and seats prior to welcoming new customers”.

The biggest challenge for the team was to demonstrate whether microwave beams were effectively hitting the surfaces and could heat them at the right temperature. Professor Nico Bruns, a polymer specialist from the University of Strathclyde explains: “My group used hen egg white proteins that are known to denature at 60°C. By looking at the solution turning white, we were able to show that the right temperature was reached to enable virus deactivation. This would be extremely helpful for an operator of the proposed system.”

Source: Heriot-Watt University

05.08.2021