It’s cool, Man!

Evidence is scant on the cooling of comatose patients who have suffered cardiac arrest, stroke or traumatic brain injuries; nevertheless, new methods for cooling patients are continuously being developed.

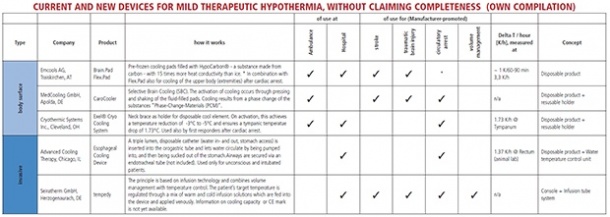

Therapeutic hypothermia is also being used in the cardiac catheter laboratory to prevent re-perfusion injury during revascularisation of coronary vessels, EH correspondent Matthias Simon reports, although noting that its use has not been documented sufficiently for this purpose. Currently available cooling methods are used either invasively (venous cooling catheters, cold infusions) or superficially (cooling pads, ice packs), or by utilising natural body orifices, such as the administration of perfluorocarbon into the nasal cavity.

There are many different views on the point at which cooling should be initiated: during re-animation, during transport to the hospital, or even only once the patient has arrived at a hospital. There are also different recommendations as to the correct target temperature: A study published in 2002 by the European Hypothermia After Cardiac Arrest Study Group showed an improved six-month survival rate (59% v. 45%) and improved neurological outcome (55% v. 39%) in 275 patients who had suffered out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHC) and ventricular fibrillation or tachycardia when they were treated with therapeutic hypothermia (target temperature range between 32°C - 34°C) compared to those given normothermic treatment [N Engl J Med 2002; 346:549-56].

However, Australian medics found a significantly improved neurological result (49% hypothermic v. 26% normothermic) in 77 patients after OHCA with ventricular fibrillation if they were treated with therapeutic hypothermia to 33°C. However, there was no significant advantage to the survival rate with 49% v. 32%. ‘After adjustment for base-line differences in age and time from collapse to the return of spontaneous circulation, the odds ratio for a good outcome for hypothermia as compared with normothermia was 5.25.’ [N Eng J Med 2002; 346:557-63].

In 2005 these results led to the development of a guideline recommending the treatment of patients with therapeutic hypothermia (32°C – 34°C over a period of 12-24 hours) after OHCA with shock-able rhythm. However, the initial high hopes for the treatment were replaced by disillusion in 2013, when Nielsen et al published the results of the Targeted Temperature Management (TTM) Trial, a prospective randomised multi-centre study on patients after OHCA, with or without shock-able rhythms. 950 patients in 36 European and Australian hospitals were randomly cooled to either 33°C (Hypothermia group) or 36°C (TTM group).

The respective temperature was maintained for 28 hours; if patients developed a temperature after rewarming, fever-reducing medication was administered for 72 hours. There was neither an improved neurological outcome nor a significant difference in survival [N Engl Med 2013; 369:2197-2206].

New goal: Cath Lab

In 2007 Dr Derek Yellen of the Hatter Cardiovascular Institute in London, UK, wrote that the potentially fatal reperfusion injury, which can occur with any percutaneous coronary intervention, can be avoided through therapeutic hypothermia before, during and shortly after the intervention [New Engl J Med 2007; 357:1121-35], basing his view on the results of a study involving 220 patients, with a subgroup who had suffered anterior myocardial infarction and had been treated with induced hypothermia below 35oC showing a reduction in the size of the infarction by 39% compared to those in the normothermic control group [Presented at Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics 2004, Washington, DC].

Dr Mathias Götberg of the Skane University Hospital in Lund, Sweden, showed a significant reduction of the size of infarction in a pilot study of 18 patients when the target temperature was below 35°C (with an initial 4°C cold infusion with endovascular cooling catheter) [Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2010; 3:400-7].

Dr David Erlinge, also from Lund, recently published different results. 120 patients were examined in nine centres in Sweden, Denmark, Austria and Slovenia, with 61 patients in the hypothermia group and 59 in the control group. Therapeutic hypothermia did not result in a significant reduction in the infarction size, or in a subgroup-analysis either. The only benefit was seen in patients with anterior myocardial infarction who were re-perfused very early and showed a significant risk reduction [J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63:1857-65].

Therapeutic cooling of patients in cardiogenic shock is also being discussed: in animal experiments, Göttingen and Freiburg researchers showed an increase in cardiac contraction capacity with an increase in stroke volume under hypothermia [Basic Res Cardiol 2001; 96:198-205 and Circ 2004; 110:A1639].

However, the central questions remained unanswered: How quickly should the temperature be lowered? When should cooling commence? What is the right temperature to cool to? For how long should the target temperature be maintained? At what speed should rewarming be carried out?

One needs to literally keep one’s cool not to lose track here!

02.09.2014