Infarction size and transmurality

A cardiac catheter is insufficient to evaluate the effects of a myocardial infarction. The size of the infarction and post-event cardiac muscle activity are crucial predictive parameters that determine therapy decisions

The size of the infarction and infarction transmurality offer important prognostic information on the future course of the disease. Research indicates a direct correlation between the size of the infarction and the probability of later complications. ‘After an infarction the patient’s cardiac function can deteriorate – he develops cardiac insufficiency. Or, the patient may experience relevant arrhythmias, which increase the risk fatal ventricular fibrillation,’ explains Professor Gunnar Lund, Senior Resident at the Clinic and Policlinic for Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf. Therefore, it is of paramount importance, he adds, to collect cardiac muscle data, which provide crucial information that determines therapy decisions.

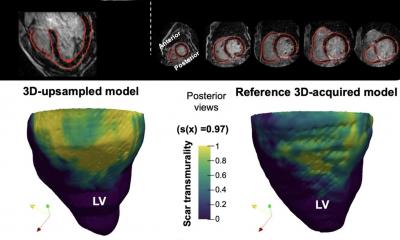

Revascularisation of a coronary artery, as such, improves neither heart function nor prognosis. The decisive factor after a myocardial infarction is the remaining myocardial viability, which needs to be assessed as objectively as possible. The acquired data can be used to risk stratify the patient. ‘Today, cardiovascular MR is the gold standard to determine size of the infarction and transmurality,’ Prof. Lund points out. The size of the infarction, for example, indicates whether a patient will require intensified cardiac insufficiency therapy after the cardiac event.

Transmurality determines actions

The second important question that needs answers: Is sufficient vital myocardium left for the patient to benefit from the improved cardiac perfusion that was achieved either surgically or interventionally? Transmurality is the parameter that provides the answer, as Prof. Lund explains: ‘An infarction always moves from the subendocardium to the epicardium, i.e. from inside to the outside. If only the internal layers are affected, and thus the infarction, transmurality is at only 10 to 25 percent, so the chances for recovery are very high. The higher the transmurality, the slimmer the chances of recovery, particularly if the infarction affected more than 50 percent of the cardiac wall.’ Based on these data the cardiologists decide whether a patient requires revascularisation – dilation – or a bypass.

Cardiovascular resonance imaging (CMR) or scintigraphy can acquire these viability data. While research indicates that both methods are equally reliable, Professor Lund prefers CMR because, in his experience, this modality allows better evaluation of the transmural extent of the infarction: ‘Scintigraphy is not quite as useful here because it has a lower resolution than CMR.’

A further disadvantage of scintigraphy, he points out, is radiation exposure since this technology requires a radiopharmaceutical to be injected. Nevertheless, at least in Germany, scintigraphy is still the most frequently used modality because of, he suspects, the unfortunate fact that the country’s statutory health insurers do not cover CMR costs.

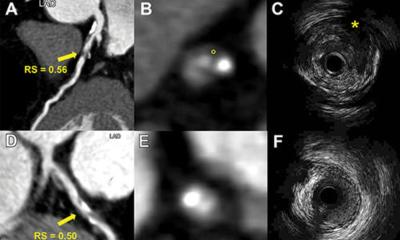

Angiography cannot reliably assess infarction size

While percutaneous transluminal coronary interventions in patients suffering an acute myocardial infarction have significantly improved outcomes, these interventions hardly yield much information on cardiac viability. ‘The size of the infarction itself cannot be assessed reliably in angiography,’ he explains. ‘There might be rather clear findings, such as a large aneurysm, which indicate a major infarction; nevertheless misinterpretations are possible since the angiography does not allow a differentiated and precise diagnosis of the size of the infarction and current viability.’ Consequently an angiography with unambiguous findings such as several coronary occlusions or stenoses is usually followed up by CMR or scintigraphy to definitely assess viability.

Profile:

Professor Gunnar Lund MD is a triple specialist – covering internal medicine, cardiology and radiology. He began medical studies at RWTH Aachen (1984), and in 1991 he joined the Department of Cardiology at University Hospital Hamburg- Eppendorf (UKE). Seven years later, Dr Lund was in the USA as a researcher in the radiology department, University of California, San Francisco, until 2000 when he continued MRI research in Hamburg. In 2004 he received his teaching qualification for internal medicine. In 2010, after two years as a general practitioner in Düsseldorf, he was appointed Professor at the University of Hamburg. He has been Senior Resident at the Clinic for Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology at UKE since 2012.

29.10.2013