Article • Disaster investigation

Identifying shipwrecked refugee casualties

Forensic radiology was, yet again, a central theme at ECR 2017, as Italian radiologists unveiled details of their work in the investigation following the shipwreck in the Mediterranean in April 2015.

Report: Mélisande Rouger

An estimated 900 people lost their lives in what proved to be the worst disaster yet involving migrants, most of them refugees from Syria and sub Saharan countries including Gambia, Sri Lanka and Ghana. For the first time, and in an exclusive interview with European Hospital, Italian radiologists in charge of forensic imaging spoke about their challenging task of identifying corpses that had been trapped under water for more than a year.

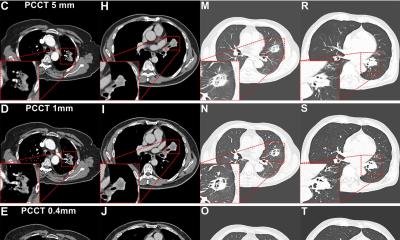

Dr Giuseppe Lo Re, a forensic radiologist from Palermo University, said he could only start imaging corpses in July 2016 because he had to wait for the rescue team to extract the bodies from the boat, which sank about 60 miles off the Libyan coast and 120 miles south of the Italian island of Lampedusa. ‘The boat was overcrowded; there were seven people per square metre. For some victims we could only identify the bone structure, so we found out which area they came from, but not which country,’ he explained. ‘Skin colour was no indicator either as it got washed out; all the corpses were grey.’ Lo Re and his six colleagues were loaned a mobile CT device for just ten days, in which they managed to identify 194 casualties.

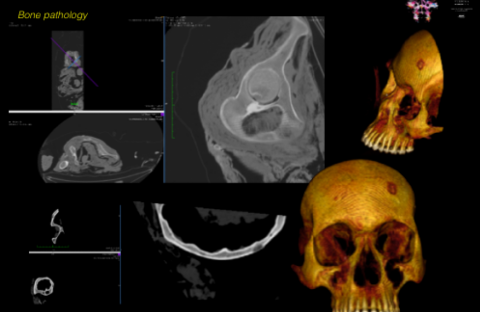

The whole benefit of forensic imaging in that context, he said, lay in the impossibility of practicing an autopsy in a decomposed corpse. ‘If you cut dissolved bodies, you will not be able to recognise anything once they are open.’ CT enabled identification of the casualties’ sex better and faster than any anthropological study. ‘Anthropology looks at particular bone lines or angles, a long and not so reliable procedure. We know the Caucasian type, but we don’t know the other types so well. Our first days with the CT were difficult because radiology can’t see these items very well. So we changed our point of view and searched for the radiological items of sex,’ he explained. ‘This was a score! We could prove that all of the victims were male.’

Lo Re and his team were also able to determine the age and death pose of the casualties, both key aspects in understanding why and how people died. ‘With CT we can study the bone nucleus, which enables us to determine if the victim was older or younger than 18, a key information in any legal investigation ,’ he said, adding: ‘The death pose is also very important in forensic science because it describes the movement immediately before death and helps to understand causes of the accident,’ A lot of the victims died because they were stuck in a lower room of the boat and because of oil residuals or water leakage during the shipwreck.

Except for the short time they had to image the bodies, Lo Re and his colleagues faced additional challenges. ‘We scanned the casualties 15 minutes each, 12 hours a day for six consecutive days,’ he said. ‘But we had to stop a whole day because of a worm invasion. I will never forget that terrible smell.

Under the water, the rescue team was also able to find wallets and phones, which helped identify who boarded the vessel. Besides their identification documents, many of the victims were carrying their university degrees with them. ‘A lot of them were engineers or medical doctors; they travelled with their certificates in order to find work in Europe,’ Lo Re explained.

The Italian anthropologists and pathologists in charge of the investigation are now faced with the complicated task of sorting out and identifying over 400 body bags, some of which, according to Lo Re, may contain as many as seven skulls. ‘It’s very hard to understand what you are seeing,’ he said, describing the dilemma. Even though he demonstrated that radiological assistance in mass disasters is possible when cooperating with anthropology and pathology, Lo Re is not sure his experience can be applied to further mass casualties, especially if there is no international cooperation to support the investigation. ‘It was important to understand how people died. But this kind of work is too big; it requires a lot of money and time,’ he pointed out.

Nonetheless this kind of work is crucial and must be carried out, he believes. ‘The Italian government said it would give a name to each person who died. To quote anthropologist Professor Christina Cattaneo, from Milan University, who is coordinating the investigation, identification of the bodies is fundamental not only for the dignity of the dead but also the living.’

26.04.2017