News • Switching sides

How cancer cells 'brainwash' their foes

It doesn’t often happen that army generals switch sides in the middle of a war, but when cancer is attacking, it may cause even a gene that acts as the body’s master defender to change allegiance.

As reported recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science have discovered that this gene’s betrayal can occur in more ways than previously appreciated.

All cells carry this gene, known as p53. It normally plays a central role in protecting the body against malignancy, orchestrating the cell’s defenses against cancer and often killing a potentially cancerous cell if those protections fail. However, in about half of all cancer patients, the p53 gene within the cancerous cells contains mutations that can result in the production of a p53 protein that not only fails to suppress cancer, but can even launch cancer-promoting activities.

Credit: Weizmann Institute of Science

This protective campaign probably often succeeds, otherwise people would get cancer much more frequently than they actually do

Moshe Oren

Besides the cancerous cells, a malignant tumor contains a variety of non-cancerous cells and connective tissue elements – a system commonly referred to as the tumor microenvironment. In the initial stages of cancer development, the microenvironment is hostile to the tumor. Prof. Moshe Oren of the Department of Molecular Cell Biology and other scientists previously found that the microenvironment cells’ p53 contributes to this hostility, blocking the spread of the cancer. “This protective campaign probably often succeeds, otherwise people would get cancer much more frequently than they actually do,” says Prof. Oren. As the cancer progresses and becomes more malignant, the tumor microenvironment gradually changes. Scientists refer to this process as “education”: the microenvironment is being co-opted by the progressing tumor into promoting, rather than restricting, the cancer. Among the co-opted cells are the fibroblasts, which supply tissue with structural “cement.” The fibroblasts initially help recruit immune cells against the cancer, but they now start releasing substances that encourage tumor growth, invasion, and survival. At this stage, these cells are referred to as cancer-associated fibroblasts.

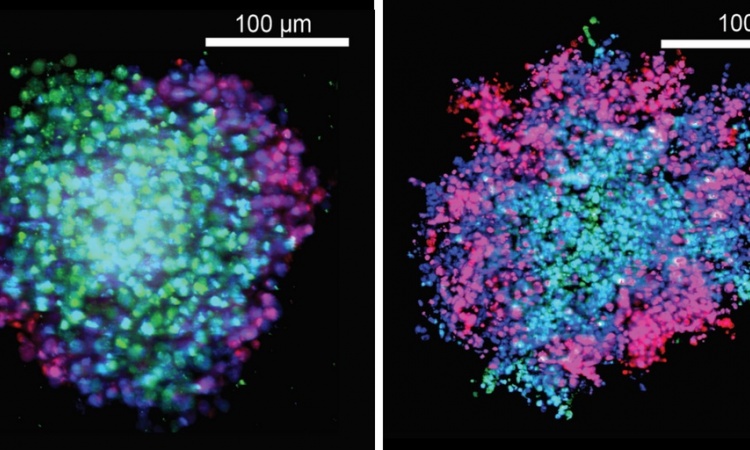

The new study, conducted in Prof. Oren’s lab in collaboration with Weizmann Institute colleagues, shows that the microenvironment’s “education” – a more appropriate term would probably be “brainwashing” – is directed in part at the fibroblasts’ p53. As the cancer grows, the p53 in the fibroblasts switches sides. Although the p53 in the cancer-associated fibroblasts doesn’t acquire mutations as it does in the cancer cells, it nevertheless becomes altered in a manner that causes it to switch from restricting to supporting the cancer.

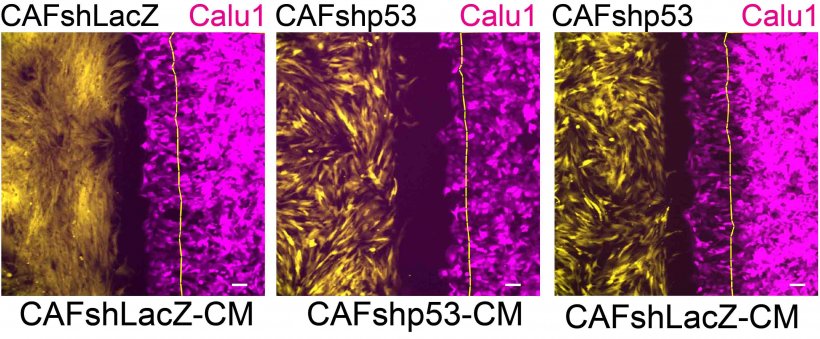

In the study, led by postdoctoral fellow Dr. Sharath Chandra Arandkar in collaboration with departmental colleague Prof. Benjamin Geiger, and with Prof. Yosef Yarden and Dr. Igor Ulitsky of the Department of Biological Regulation, the researchers showed that eliminating the p53 protein from cancer-associated fibroblasts by silencing their p53 genes caused these cells to lose many of their tumor-supporting features and behave more like normal fibroblasts. In particular, the silencing of fibroblast p53 reduced the migration of adjacent cancer cells in a laboratory dish – a crucial change, considering that invasive migration facilitates the metastatic spread of cancer. Moreover, the silencing of p53 in cancer-associated fibroblasts greatly reduced the ability of these cells to promote tumor growth in mice.

Finding ways to “re-educate” the renegade p53 in the tumor microenvironment – to reverse its behavior so that it is again suppressing tumors – may pave the way to the development of novel therapies that will target the microenvironment rather than the cancer cells themselves. Indeed, strategies targeting the cancer microenvironment are today being increasingly explored. The hope is that they might provide a new window of opportunity for launching an effective therapy, because the microenvironment tends to evolve more slowly than the mutation-ridden tumor cells.

Source: Weizmann Institute of Science

27.07.2018