High volume mammo centres yield high quality research

With 350,000 mammography screenings annually, Unilabs Sweden finds itself on the leading edge for research in mammography and pioneering patient education programmes. John Brosky reports

unsurprisingly, prototypes for every new modality in breast imaging are found at one or another of the 23 mammography centres managed by Unilabs Sweden. In addition, as the centres perform more than 1,500 breast cancer screenings per day, it also is quite expected that research institutions are keen to conduct studies within this network, which covers half the women in Sweden. What is unusual here is the enthusiasm and passion for this leading edge work among a very busy staff in an efficiently run private company necessarily focused on high patient through-put. Even more surprising is the company’s financial support for multiple studies, the largest of which will not be finished for 10 years.

Landmark studies to be reported

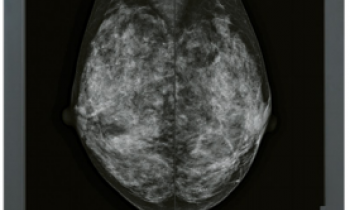

The European Congress of Radiology will present a study showing a 57% higher detection rate for cancer with automatic breast ultrasound (ABUS) compared to conventional mammography will be presented. The study of 1,671 asymptomatic women with dense breast tissue was supported by Unilabs and conducted at its centre at Capio Saint Göran Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden. Preliminary results from the ‘Malmö Breast Tomosynthesis Screening Trial’, reporting data on 9,000 exams of women with dense breast tissue, is now being prepared for publication. Unilabs joined the Skåne Region to sponsor this three-year study that will ultimately include 15,000 women. ‘This work is a big part of our daily routine in practice,’ explained Karin Leifland MD PhD, Head of Mammography for Unilabs Sweden. One year ago, the Unilabs centre at Lund University joined the Karma study being conducted by the Karolinska Institute to identify risk factors for breast cancer among 70,000 women. Each patient who agrees to participate completes a lifestyle questionnaire, allows an assessment of her breast tissue density and undergoes a blood work up for genetic information. According to the lead investigator, Karolinska Professor Per Hall, ‘The Karma study is now recruiting almost a thousand women a week, which is a stunning figure. Without Unilabs Skåne’s cooperation this could never have been possible.’

The goal of the Karma study is to create the world’s best-characterised breast cancer cohort by following the patients to see who develops breast cancer over 10 years and then determine why. There are three MRI studies underway at Unilabs centres. One follows women with a hereditary risk of breast cancer, which compares the results of conventional mammograms with ultrasound examinations and finally an MRI exam. A second MR study funded by Unilabs is for a doctoral thesis on vacuum biopsy. The third is for pre-operative diagnosed breast cancer that randomises patients with one group undergoing an MR exam to see if more cancer is detected than in the mammograms and ultrasound. It helps that Swedish women are the nicest mammography patients in the world, Dr Leifland points out. ‘When we ask them to take a biopsy for tissue samples, they say, “OK”. They are really interested in participating in various studies because they know even if it may not benefit them, it may benefit their sisters.’

Pioneering Preferential Rf Ablation studies

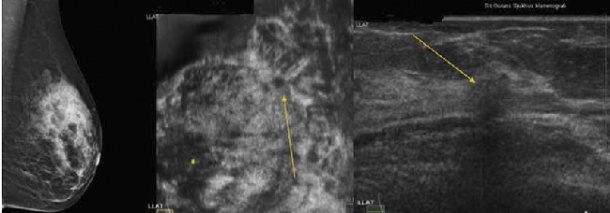

In collaboration with Capio St Göran Hospital and the Karolinska Institute, Unilabs is validating the efficacy of Preferential Radio Frequency Ablation (PRFA) in a study with three patient cohorts. In this procedure a well-defined, solitary tumour of less than two centimetres is targeted using ultrasound so that a thin electrode can be inserted. PRFA technology induces an enzymatic destruction of the tumour by heating it for 10 minutes between 70 and 90 degrees Celsius. Surrounding fibrous and fatty tissues are left unharmed. The first patient group are women already on the operating table. Immediately following the ablation, the tumour is surgically removed for a study of the heatinduced effects. A second cohort of patients in this group is asked to wait three weeks before the tumour is removed surgically.

The third group are much older women who cannot undergo surgery. After treatment they are followed with imaging exams to determine if the tumour has been destroyed or if the cancer returns. ‘We have completed this procedure on 55 women, six of whom are in the third group, and not one has any cancer left,’ said Dr Leifland. The experimental approach without surgery could never be applied to younger women, she explained. But the older patient cohort allows the group to validate the effectiveness so that with enough evidence it may someday be performed on younger women. ‘If we can do this – identify women with a tumour, ask them to come back in a week, heat it up for 10 minutes and know that it is gone – that,’ she declared, ‘will already be a fantastic outcome.’

Crossing cultural barriers to save lives

Immigrant children can play a key role

Unilabs also supports patient education to help the Swedish health ministry meet an ambitious goal of regularly screening 80% of women for breast cancer.

‘We are at 94% participation in some areas but only at 47% in others,’ explained Karin Leifland, who heads the Mammography group for Unilabs Sweden. The target group for a new campaign at Unilabs’ centres is women who have immigrated to Sweden from Africa and Arab-speaking countries and who do not share the same cultural motivation to participate in screenings as Swedish women.

Where Swedish women have an incidence of breast cancer 30-40% higher than the immigrant population, an immigrant woman in Sweden is 30-40% more likely to die of breast cancer because the condition is not detected until in an advanced state.

The first challenge, says Dr Leifland, is the high rate of illiteracy among the large populations of these women in urban areas. The Unilabs Sweden team revised its invitations to come for a screening so that a seven-year-old child, who often is asked to read the letter, can tell his or her mother why she should go for a screening.

Once the woman does come for a screening she is given a key ring holding four rubber balls ranging from 24 millimetres in diameter to just 3mm. The staff explains that the largest ball is the average size of a tumour that the woman will be able to feel when palpating her breast. The next is the average size of what a doctor would feel and the third is what can be seen in a mammogram. The smallest, she is told, is the size of a tumour the Unilabs radiologists will be able to see if the woman comes for follow up visits, when they can consult her prior exams.

‘Yes, it works!’ Dr Leifland said, explaining it is effective with a woman who thinks that having visited once, she does not need to return the next year.

10.02.2013