Article • Discussion

Genome editing: Should we tweak human evolution?

According to Darwin, humans will one day become extinct. Some don’t think we need to accept this fate because gene editing may allow us to use our brains to take over the evolutionary story.

‘Why, if we believe in evolution and the risk that one day humans will become extinct, should we not use our brains to take over our own evolutionary story,’ philosopher Françoise Baylis will ask on 13 June, during her plenary session talk on ‘Human gene editing: The dawn, the zenith, and the dusk’ at the Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine annual congress, being held in Athens, Greece.

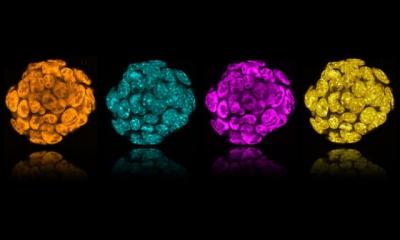

Professor Baylis, Chair in Bioethics and Philosophy at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada, and an acknowledged authority on the ethical issues of manipulating the human genome, was a member of the organising committee for the first-ever International Summit on Human Gene Editing. As she recently wrote, since its discovery the gene-editing system known as clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) has been used by scientists to make precise alterations in the DNA sequence of living cells. This offers the prospect of treating, and perhaps even eradicating debilitating genetic conditions, improving fertility treatments and fighting cancers. On the other hand, the professor stated, for some people CRISPR also raises the spectre of a bioethical nightmare that opens the door to large-scale bioterrorism or monstrous genetically altered human variants.

I still believe that genetic enhancements are inevitable

Françoise Baylis

The ethical questions of whether we should use this technology, and for what purpose, remain unanswered. ‘I wrote, more than ten years ago, and I still believe, that genetic enhancements are inevitable,’ she said in an interview with European Hospital. ‘Someone among us will do it. I could give the best ethical argument possible why we should not do it, and nevertheless some person will do it. And once that person does it, we all will be off to the races. At the end of the day we are speaking about the biggest project imaginable, yet the current discussion of gene editing is not productive. This is because our debate tends to polar extremes either saying this is terrible, we should never do it, or this is great, we should go ahead,’ Baylis said.

Before moving on to a discussion of good and bad, Baylis set the table for gene editing where the potential benefits and risks split into two parallel sets. The first set makes a clinical distinction between the types of cells being manipulated, whether they are somatic cells or germ cells. Simply put, somatic cells are cells in the body of the person being treated and once manipulated the resulting cells stay in the body of that person. Germ cells, on the other hand, are eggs and sperm, and early-stage embryos. The effects on these cells are passed on to any children created by the person who has undergone a treatment.

Are we treating? Or are we trying to make better humans?

The second great divide in gene editing addresses the clinical intention. Is the manipulation of genes for a therapeutic effect, such as preventing, curing or correcting a disease, or is it for enhancement where human characteristics for everything from muscle mass to eyesight can potentially be manipulated. The ethical issues begin with a question of intention, she said. What are we trying to do? Are we treating? Or are we trying to make better humans? ‘The field today is divided with respect to which of these categories of activities should be pursued. People are generally supportive of therapeutic interventions in somatic cells, though this is not risk-free. Things could go wrong. This is research, after all. But there is a broad agreement to go ahead,’ she said. ‘People are not in agreement with respect to enhancement, even in somatic cells,’ said Baylis. ‘Yet others are quite enthusiastic and do not see why we would not want to make ourselves a better species. But when we look at germ-line editing, there are people who say this is the Rubicon, it is a line we should not cross; we should never do anything in the germ-line whether for therapy or enhancement. The germ-line is off limits.’

The risk of one person going forward alone into germ-line editing is huge, she said. ‘There are people who wish to be recognised as being the first, being the brightest. We live in a world that not only fosters but also rewards that kind of competition. ‘And people rightfully worry about the societal effects of this kind of intervention. There are concerns about eugenics and discrimination resulting from the fact that some people will have access to these expensive technologies while other people will not. That some could benefit from something not available to others,’ she said. ‘I want us to accept the fact that some kind of gene editing is in our future, and to stop arguing about ‘go’ ‘no-go’. Instead, we should focus on what we can do right now to assure that whatever is done will be done for the benefit of all of us and not just for a minority who are wealthy enough or powerful enough to do this,’ said Baylis. ‘I am interested in how we will negotiate – when we have never done so before – a broad societal consensus of how to use this technology for the benefit of all. We have time to learn. The science is not there, yet,’ Baylis concluded. ‘While scientists are doing that work, why shouldn’t we figure out how to have a meaningful conversation, as one people across the planet, so that it’s actually possible to be humane, and not just human?’

Profile:

Professor Françoise Baylis is an acknowledged bioethics expert with a special focus on genetic modification. Her aim is to “move the limits of mainstream bioethics and develop more effective ways to understand and tackle public policy challenges.” She is a member of the Order of Canada and the Order of Nova Scotia, as well as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and a Fellow of the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences.

14.06.2017