Future radiology infrastructures

When asked about his vision of imaging in the year 2020, Professor Bernd Hamm MD, director of the three radiology clinics at the Charité University Hospital in Berlin, qualified his focus: ‘Technology is always only a vehicle. When we talk about road traffic, we don’t talk about the design of cars but about structural issues’

‘Radiology will increasingly be organised in centres in, at and around hospitals that provide both in- and out-patient services,’ Professor Hamm predicts. In, at and around are more than spatial descriptions. They are associated with content. ‘In the hospital’ refers to centres operated by the hospital or a medical care centre; ‘at the hospital’ describes centres jointly operated by hospitals and office-based radiologists and are located at the hospital and ‘around the hospital’ are interdisciplinary medical co-operations located in the hospital where equipment is jointly used.

In such an environment, he is convinced that interlinkage of in- and out-patient care will increase. ‘There will be a concentration process in the in- and out-patient departments and the combined areas that will lead to significantly larger units than we currently have.’ In the future, he adds, regional radiology co-operations and teleradiology networks will serve smaller healthcare facilities. Thus outpatient centres with more than 20 specialised physicians are likely to fare well.

This centralisation, he explains, ‘is not only a result of economic pressure, but also of the increased specialisation in the medical profession’. The different clinical disciplines want and need ever more specialised high quality radiology because they heavily rely on imaging. However, today’s economic and clinical interests sometimes conflict. Specialisation has created high clinical competency, as the professor notes: ‘Today, radiology is extremely good at diagnostics and thus assumes more clinical responsibility. The full potential of these two skills – imaging and diagnosis – has to be exploited. This, however, requires radiologists to be more closely involved in patient management and responsibility for the patient.’ In the coming years, he anticipates a significant increase in imageguided minimally invasive treatments. On the other hand, emerging clinical disciplines increasingly want to integrate areas of imaging into their realms – such as MRI or many interventions. ‘Continuing training committees, physicians‘ associations and other medical bodies need to ensure that radiology maintains its sharp profile and broad range,’ he emphasises.

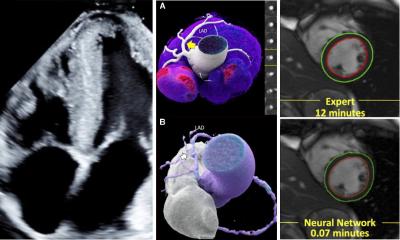

Hybrid imaging

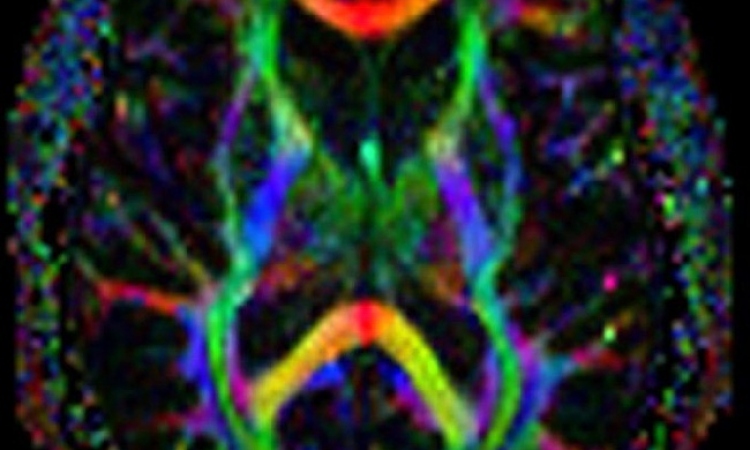

Prof. Hamm predicts that hybrid imaging, a combination of PET/CT, MR/PET or SPECT/CT, will shape the future of imaging. Yet again, it is not so much the technological wizardry that interests him, but the structural setup: ‘Radiology and nuclear medicine will move closer together. In the mid-term I expect the combined specialist physician for diagnostic radiology and nuclear medicine to materialise. Image fusion is also more than a buzzword for the professor, because ‘it is challenges radiology to expand its competencies – in all areas of slice imaging and ultrasound.’

He is convinced that image fusion, contrast-enhanced ultrasound and ultrasound elastography will give a boost to sonography and this modality will regain significance in radiology. Last, but not least, there is molecular imaging. ‘At the moment the initial euphoria has given way to certain disillusionment. Molecular imaging has yielded spectacular results in experiments. However, translation into clinical practice – with the exception of nuclear medicine – has not been successful.’ Molecular imaging, he adds, will only prevail if the technology can prove not only diagnostic but also curative relevance. Negative case in point: tracers to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease. ‘What use is it to be able to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease but the diagnosis does not have any therapeutic implications because, at this point, no treatment is available?’

10.07.2012