Article • Ultrasound

Controversies and practices in breast cancer screening

Comparisons in Germany, Austria, Switzerland

A controversy regarding the benefit of early screening programmes for breast cancer continues. Germany, Austria and Switzerland have developed individual strategies. European Hospital asked three experts from these countries to outline each chosen system.

GERMANY: A quality-assured mammogram screening programme

Amongst the German-speaking countries, Germany has the longest running standardised screening for early detection. In June 2002 the German Parliament voted unanimously to introduce a mammography screening programme for women aged between 50 and 69. Thus, in 2003, the Mammography Cooperative was founded to be responsible for coordination, quality assurance and evaluation of the programme. This programme is aimed at more than ten million women and is the first systematic cancer screening programme in Germany based on European quality standards, and the largest screening programme in Europe.

‘Mammography is the only imaging procedure proven to reduce mortality in a screening setting if it is carried out with quality assurance,’ explains Professor Markus Hahn, Head of Experimental Senology at the Centre for Breast Diagnostics, University Hospital Tübingen. In the collective examined, i.e. women without a known, high familial risk, we diagnose cancer on average in seven in 1,000 women,’

Quality assured means that there must be a primary and secondary diagnosis (four eyes principle). Conspicuous results are discussed at a consensus conference and a decision is made as to whether further investigations are necessary. Too many false-positive results are not of benefit for the screening programme. ‘We cannot investigate results from too many patients and we need a high hit rate if the programme is to be successful,’ Hahn explains.

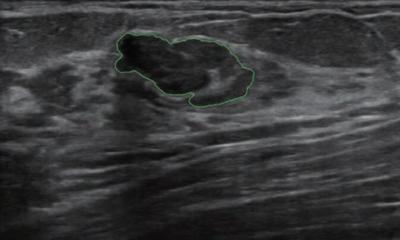

Ultrasound closes the gap in cases of dense breast tissue

Under certain conditions, mammograms can have disadvantages, especially when the breast tissue is very dense, which is difficult for the examiner to differentiate between tumour tissue shown in white and breast tissue also shown in white – akin to looking for an artic hare in snow. ‘This is where ultrasound has a major advantage, because these results are visualised in a different way on an ultrasound image. Data has shown that the detection rates for breast cancer, with the additional use of ultrasound, can be significantly increased for breast tissue density grades three and four,’ Hahn explains. ‘However, at present we do not have the prerequisites to carry out ultrasound examinations for all women with breast density grade three or four in the context of screening. We also lack the examiners needed with the respective expertise.’

The German, Austrian and Swiss Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine (DEGUM, ÖGUM and SGUM) have the big responsibility of running the appropriate training courses for doctors to ensure that the false-positive rate can be kept as low as possible. Hahn therefore advocates additional ultrasound examinations only for those within the group of postmenopausal women with breast density grade four, who are also already at an increased risk of developing breast cancer. ‘But first we need to prove within an actual screening-setting with a normal collective that this helps to reduce mortality,’ Hahn points out, ‘otherwise nobody will want to cover the costs involved. Therefore, great efforts are currently being made from every direction to initiate a study for this, as soon as possible. However, this also means that training in ultrasound must be intensified as only those who have benefitted from the appropriate training will be able to detect even the smallest changes.’

A Quality Circle for Ultrasound was founded in Tübingen for this purpose, and Hahn has seen great progress amongst the participating gynaecologists regarding confidence and capability during examinations. ‘Training is the be-all and end-all,’ the consultant notes. ‘Diagnostics at the highest level is offered in Germany with the help of quality assurance, guidelines, certification of breast centres and structured courses offered by DEGUM. All process chains from screening to aftercare are meticulously planned, which is both important and exemplary.’

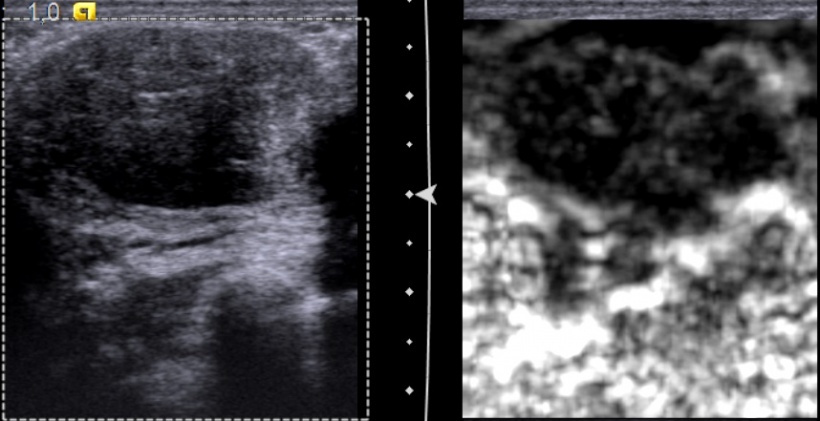

Current innovations in fusion imaging, where mammography and ultrasound images are generated by a fusion scanner and then processed at the workstation, are also of interest for screening. Standard introduction of this technology would notably shorten the examination time and would allow the examiner to make a diagnosis while looking at both images in parallel. Therefore, in the context the use of large-scale screening should also be possible, but the procedure is currently still in its infancy. In Hahn's view, high-resolution ultrasound is the senologist's ‘eye’ - a fast and high-resolution procedure without radiation that facilitates a clear differentiation between pathology and anatomy.

AUSTRIA: The breast in the radiologist's hand

From 2014, Austria has offered a systematic and quality assured breast cancer screening programme (BKFP) to the target group of women aged between 45 and 69 with bi-annual examination intervals. Additionally, women aged between 40 and 44 or 70 and above can also opt into the programme. The Austrian BKFP is a joint initiative set up by the Government, the individual Austrian States, Social Security and the General Medical Council and replaces all previous mammograms offered for breast cancer screening prior to 2014, specifically the opportunistic, i.e. non-systematic mammogram screening programmes that existed in most Austrian states. This includes all previous offers in the context of screening, or referrals outside of systematic screening and all organised screening programmes initiated as pilot programmes, such as the Tyrolean Mammogram Screening Programme.

Despite a long pilot phase in individual states, it appears that the first step is always the hardest proves true. Senior Consultant Dr Martin Daniaux, Head of Breast Diagnostics at the Breast Health Centre Tyrol in Innsbruck, the largest out-patient breast centre in Austria, admits that the Austrian BKFP is currently experiencing some teething problems. The new guidelines, which include a move away from the usual doctor's referral, have led to some uncertainty amongst doctors and patients and, as a result, a lower uptake of the breast screening programme.

Around 37% of women within the target group took up the offer during the first round of screening (2014/15), which is much lower than the 70% uptake rate stipulated in the European guidelines. Radiologist Daniaux, who was also involved in the pilot Tyrolean Mammogram Screening Programme, has also seen the participation rate in Tyrol reduced by half compared to figures prior to 2014. ‘Due to the low participation rate, there is currently no reliable data on the BKFP in Austria. Furthermore, any potential reduction in breast cancer mortality can only be determined once a successful programme has run for at least ten years. In any case, a lot definitely remains to be done until then,’ he concludes, and is convinced of the prevailing benefits of a well-organised screening programme.

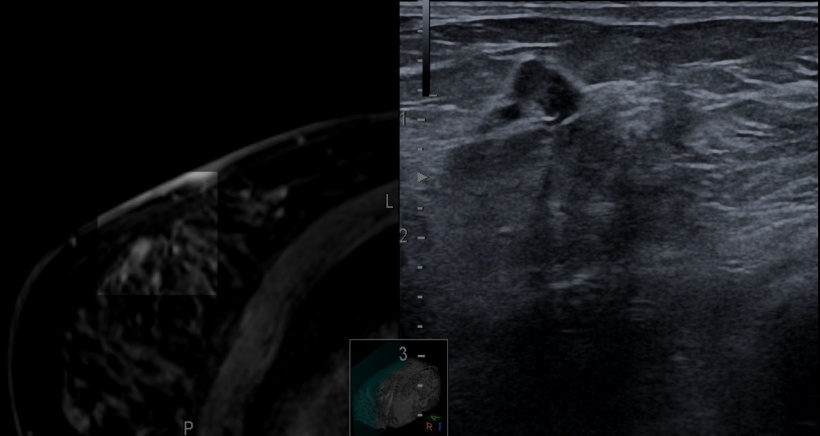

‘The large advantage of the Austrian BKFP is the implementation of additive ultrasound in the screening setting. Mammography and ultrasound can be carried out during the same appointment and are calculated as one service for billing purposes. Although ultrasound is not mandatory for ACR C and D in Austria it is still carried out for many patients, Daniaux explains, as someone who makes a primary diagnosis and has the power to decide immediately after the mammogram if a patient also needs an ultrasound or not. ‘In Austria, ultrasound has been traditionally part of breast cancer screening, and patients also demand it.

‘It increases the sensitivity of screening; however, whether or not it also leads to more false-positive results cannot yet be confirmed for the Austrian BKFP. By offering screening from the age of 45 it’s also hoped to increase the detection rate for early-stage breast cancer. Daniaux assumes that most premenopausal patients, i.e. those with particularly dense breast tissue, are also given an additional ultrasound.

Ultrasound immediately after a mammogram is possible in Austria because qualified radiologists carry out the entire breast diagnosis. Only specifically trained and accredited specialists with skills in mammography, ultrasound and MRI work in the screening units. The programme also stipulates secondary diagnosis, along with a location and staff specific minimum number of screenings. Unlike Germany and Switzerland, almost all patients in Austria are given an MRI scan during preoperative staging because it has high sensitivity with low specificity.

One of Daniaux’s specific areas of focus is the fusion of ultrasound and MRI. Particularly for second-look ultrasound after MRI, fusion mostly allows a safe classification of incidental enhancing lesions (IEL); the diagnosis is not delayed and complex MRI biopsies can be avoided in some cases.

SWITZERLAND: No national consensus

In Federal Switzerland, where each of the 26 cantons is responsible for its own healthcare system, there is no nationwide breast screening. Only 12 cantons have quality controlled, population-based mammography screening programmes. All other cantons arrange opportunistic screenings after referral by a gynaecologist or GP. ‘The advice for opportunistic screening is that women aged 50 and above should be screened every other year, and the state has put recommendations on screening in place for women at higher risk, with screening covered by the health insurers,’ explains Dr Serafino Forte, Senior Physician in the Radiology Department at the Cantonal Hospital Baden.

The quality requirements of the European guidelines apply within the screening programmes. Forte explains that quality-controlled programmes, unlike opportunistic screening, implement an independent, secondary diagnosis of mammograms. Discrepancies and results that require clarification receive a third diagnosis during screening and are discussed at consensus conferences.

The higher quality of programmes compared to opportunistic screening can be measured because the detection of small and node-negative lesions within the programmes is substantially higher than outside the programmes. Women with high breast density ACR D and inconspicuous screening mammograms are recommended to have an additional ultrasound examination. This ultrasound is not part of the screening programme in Switzerland, the radiologist explains.

Ultrasound is used as a supplement for opportunistic screening. It is normally used for regions that are only assessable with limitations in the mammogram and for women with high breast density ACR D. ‘The newer mammography devices also offer tomosynthesis. This facilitates very good assessment of breasts with ACR C and means that we don’t necessarily need to carry out an ultrasound,’ says Forte, who regrets that screening is not carried out in his canton of Aargau. ‘Mammography is not perfect because there are, unfortunately, false-positive and false-negative results and unnecessary interventions. However, we do not currently have another method to offer for screening a large number of women in a cost-efficient way. Quality-controlled mammography carried out in the context of a screening programme cannot prevent breast cancer. But we can detect cancer at an early stage and, in many cases, this allows us to cure women of cancer.’

Screening is consistently discussed in Switzerland. A 2014 report from the Swiss Medical Board (SWB) caused controversy because it concluded that the programme would do more damage than it would help women. Forte points out that many studies that oppose screening are based on data that is, in parts, more than 30 years old. ‘In those days,’ he points out, ‘there were no fully digitalised systems that improved diagnostics. In Scandinavia they are currently working on a large study that includes tomosynthesis. This data is very promising regarding the detection rate, the false-positive results and biopsies.’

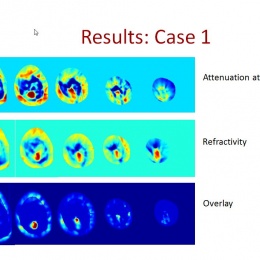

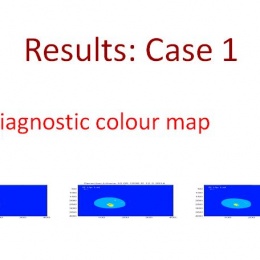

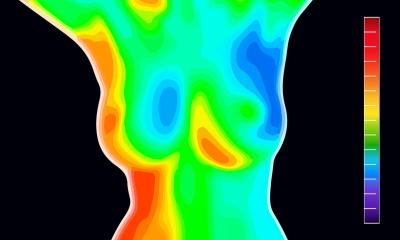

Forte sees the future of early detection and screening in automation. In Basel he had very good experiences with a prototype of multimodal ultrasound tomography (MUT). Similar to a CT scan, the breast is circled by sensors, but the transmission is measured with ultrasound waves, which means there is no exposure to X-rays at all. Special algorithms produce colour cards and the respective findings light up in different colours.

‘It’s still a prototype and the data is not yet validated, but the first data published has achieved a sensitivity of more than 90%,’ he explains. ‘The advantage of this technology is that the evaluation is fully automated and user-independent. It’s also more comfortable for women because the examination is carried out without X-rays or compression.’ Forte does not believe in the necessity of fusion because, these days, most modalities can be very well correlated with one another.

Profile

Markus Hahn MD studied in Heidelberg and wrote his thesis on tumour cell dissemination in breast cancer. He is a gynaecologist and obstetrician and, since 2005, has been senior consultant at the University Breast Centre in Tübingen. In 2011 he wrote his habilitation on the subject of minimally invasive breast interventions and in 2016 he was appointed professor for experimental senology. His scientific focus is on imaging procedures and oncoplastic and reconstructive breast surgery.

Profile

Following his degree course and postdoctoral course at the University of Vienna, from 1990 – 1995 Martin Daniaux MD trained as a general practitioner at Feldkirch Regional Hospital. He moved to the University of Innsbruck, and qualified as a radiologist in 2001, then became Head of the Department for Breast Diagnostics in 2009. He now runs courses for ÖGUM and is an author and co-author of scientific publications. He also lectures and leads courses on breast diagnostics at home and abroad.

Profile

Following his medical degree at Freiburg and Zurich Universities, Serafino Forte MD trained in general surgery and then qualified as a radiologist at Basel University Hospital in 2014. His training also included a one-year fellowship in abdominal and oncological imaging with a focus on breast diagnostics. He then became a Senior Consultant and Assistant Director of the Department for Breast Diagnostics at Basel University Hospital. Since 2016 he has been a Senior Physician at the Baden Cantonal Hospital in Brugg, and a lecturer at the University of Zurich, where he is in charge of the Elective Module for Mammography.

25.10.2017