Concerted efforts to combat prosthetic joint infections

Report: Karoline Laarmann

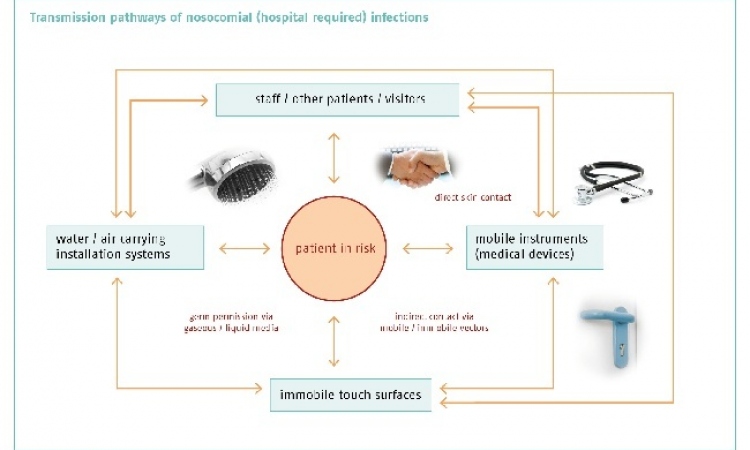

Bacteria are highly flexible when it comes to choosing a vehicle to enter a human body. During orthopaedic surgery, they may well settle on a prosthetic joint and cause immediate or delayed infections.

At the 12th EFORT (European Federation of National Associations of Orthopaedics and Traumatology) Congress this June, Dr Andrej Trampuz, senior physician and leader of the research team at the Division of Infectious Diseases, University Hospital (CHUV) and University of Lausanne, Switzerland, offered an update on the diagnosis and treatment of prosthetic joint infections.

Joint prosthesis infections -- they can happen anywhere, even in the squeaky cleanest of operating theatres and despite rigorous precautions such as perioperative antimicrobial prophylaxis.

Bacteria, airborne or through contact, reach the surface of the prosthesis where they form clusters and trigger the infection. Depending on the surgical technique and on tissue anatomy infection rates vary between 1% (knee) and 5% (ankle).

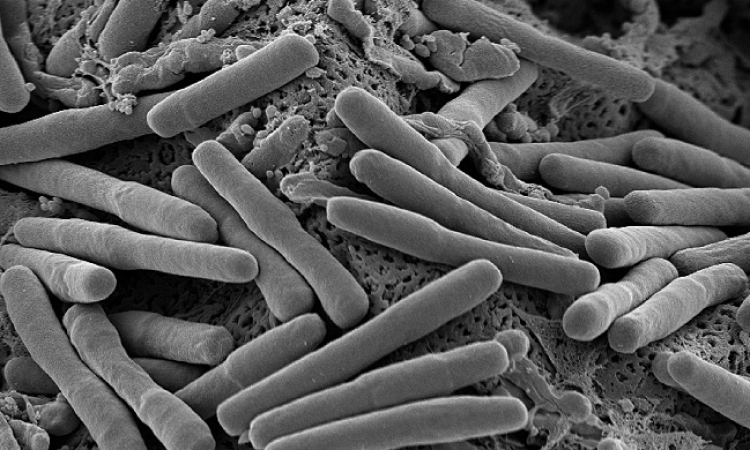

The wide range of pathogens encompasses highly virulent microorganisms such as S. aureus as well as less virulent microorganisms such as S. epidermidis. ‘We distinguish between high-grade and low-grade infections,’ Dr Trampuz explained. ‘High-grade infections appear within three months. These acute infections require a quick response. If follow-up surgery is performed within three weeks of the first occurrence of symptoms and if the mobile parts of the implant can be replaced the prosthesis, as such, can be maintained. For the patient this means less tissue damage and less bone loss. This intervention obviously requires the infection to be diagnosed correctly.’

Low-grade infections may even be more difficult to diagnose since the onset of symptoms can take three to 24 months. After such a long period the link between nonspecific symptoms and the surgical intervention in the past is not always immediately clear. ‘It is important to inform the patients about possible infections while they are still in hospital so they can contact their orthopaedic surgeon right away when symptoms appear,’ he emphasised. In the hospital, orthopaedic surgeons and infectiologists form an interdisciplinary team to treat patients with prosthetic joint infections. Dr Trampuz closely cooperates with his colleague, orthopaedic surgeon and traumatologist Dr Olivier Borens, who heads the Department for Septic Surgery at CHUV.

However, pain does not necessarily indicate an infection. If the implant is not placed correctly, biomechanics can cause the pain. Usually an x-ray examination and a joint aspiration are performed in order to determine whether septic loosening (infection) or aseptic loosening (mechanics) occurred. The aspired fluid is tested for bacteria. ‘Since the prosthesis has to be replaced in any case the patient may opt for immediate surgery. During the procedure samples are taken from the tissue,’ Dr Borens explains.

The surgeon makes two options: ‘In most cases the prosthesis is replaced to preserve the function of the joint. However, this means, that the new part will also be infected. Consequently, a suitable antibiotic is needed that efficiently combats the bacteria. But the surgeon can also decide to replace the prosthesis after two, four or six weeks. In this case the microorganisms stay in the bone for some time. No matter which procedure is chosen, the type of bacteria has to be known to be able to launch the appropriate antimicrobial therapy.’

Today, the gold standard for the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infections is an ultrasound procedure called sonication, which increases sensitivity compared to joint aspiration from 60% to 90%. Since the microorganisms grow biofilms on the implants they are difficult to detect in the surrounding tissue. During sonication, rather than taking untargeted samples from the tissue around the prosthesis, the entire implant is immersed in an ultrasound bath: the biofilm is removed from the implant with the help of ultrasound.

The sonication fluid is then analysed in the lab. A resistance test is a quick method to determine the appropriate antibiotics therapy. ‘If you do not have sonication equipment the removed implant can be sent to a lab where it is tested,’ Dr Trampuz points out. ‘In Switzerland alone we have more than twenty such centres. It is important that all orthopaedic and traumatology departments know these options so that we can increase the success rates of prosthetic joint infection therapies.’

16.06.2011