C. difficile increases death risk six-fold in IBD cases

Screen patients on admission!

The UK -- Patients admitted to hospital with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) face a six-fold greater risk of death if they become infected with Clostridium difficile, according to a new study carried out by researchers at Imperial College London and St George’s Healthcare NHS Trust (pub: Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics).

The researchers conclude that IBD patients should be screened on admission to protect them from serious illness.

IBD, consisting of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, affects around 240,000 people in the UK. Symptoms include abdominal pain and diarrhoea. When sufferers experience a bout of severe symptoms, they often need hospitalisation.

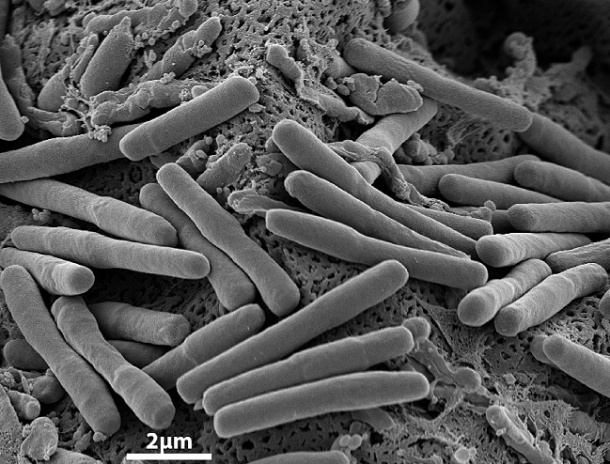

Although C. difficile bacteria reside naturally in the gut in around two thirds of children and 3% of adults, causing no problems in healthy people, antibiotics can kill harmless bacteria in the gut, allowing C. difficile to flourish and produce toxins that cause diarrhoea and fever.

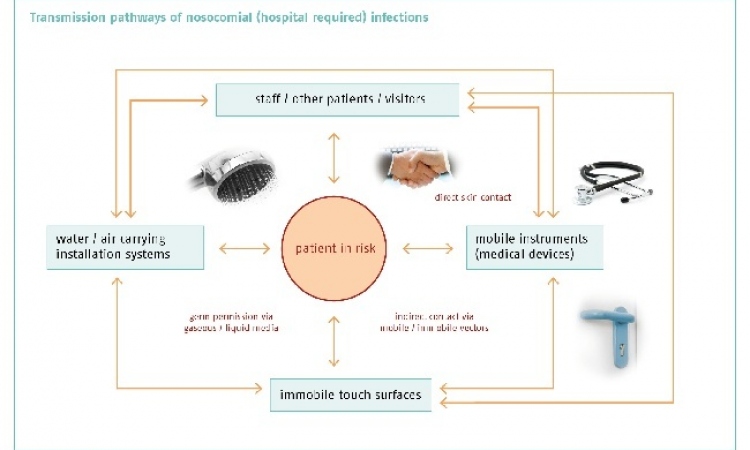

Measures to cut the spread of infection, such as improved hospital hygiene and changing antibiotic policies, have had some success, but high-risk patients are still not always adequately protected. Since IBD patients already suffer gut inflammation they are thought to be especially vulnerable to C. difficile infection, but the incidence of infection in these patients in the UK was unknown until now.

For their study the researchers examined NHS statistics on patient admissions between 2002 and 2008. After adjusting for differences between the groups, they found that IBD patients who contract C. difficile in hospital are six times more likely to die in hospital than patients who are admitted for IBD alone. In the patients followed in the study, the mortality rate for IBD patients with C. difficile at 30 days was 25%, compared with 3% for patients with IBD alone.

The results also showed that IBD patients with C. difficile stay in hospital longer -- a median stay of 26 days compared with five days -- and are almost twice as likely to need gastrointestinal surgery.

The study’s senior author, Dr Richard Pollok, of St George’s Healthcare NHS Trust, pointed out that although St. George’s Hospital has seen a 70% reduction in nosocomial infections after implementing control measures such as careful hand washing and reduced use of broad spectrum antibiotics, ‘We need to do more to protect vulnerable patients such as those with IBD’.

Dr Sonia Saxena, from the School of Public Health at Imperial College London, said: ‘Hospitals must do everything they can to control infections such as C. difficile. We are asking for these high-risk patients to be screened for C. difficile proactively on admission to hospital so that if they are exposed, they can be diagnosed and treated more quickly.’

14.06.2011