© Christina & Peter – pexels.com

News • Analysis explores reasons behind fake news

Getting to the bottom of the 'holiday suicide' myth

The suicide rate is at an all-year low at holiday time, but the myth that it rises endures – but why? An analysis of the past year showed again that more newspaper accounts supported the false idea that the suicide rate increases during the holiday season than debunked it.

Over the past 25 years, researchers at the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC) of the University of Pennsylvania have been studying this phenomenon, in just over a third (nine years or 36%) they found more debunking of the myth than support for it. Despite years of debunking by mental health researchers, journalists, and others, the misconception that people are more likely to die by suicide over the holidays has shown remarkable persistence. “For more than a generation, we’ve been analyzing how the news media report on the mistaken belief that the suicide rate increases over the holiday season,” said Dan Romer, research director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC) of the University of Pennsylvania. “The persistence of this myth suggests that its hold on the public’s imagination is difficult to undo. Supporting the myth serves no useful purpose and may have a contagious effect on vulnerable people who are experiencing a crisis and contemplating suicide during the holidays.”

There’s no need to give people the false impression that others are dying by suicide, when that could actually lead to contagion

Dan Romer

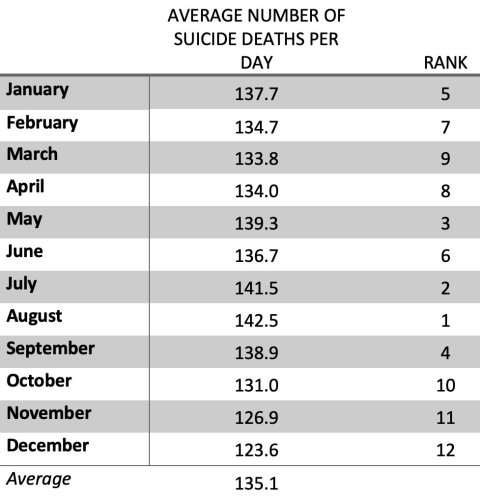

A nationally representative survey from 2023 shows that this narrative sticks: Four out of five adults incorrectly picked the month of December over several other months as the “time of year in which the largest number of suicides occur” – even though the other months provided as potential choices typically have much higher suicide rates.

“The holiday blues are a real phenomenon that might require attention to loved ones who might be sad at this time of year,” Romer said. “People may feel sadness around the holidays for many different reasons. There’s no need to give people the false impression that others are dying by suicide, when that could actually lead to contagion.”

National recommendations for reporting on suicide advise journalists not to promote information that can increase contagion, such as reports of epidemics or seasonal increases, especially when the claim has no basis in fact. The recommendations, which were developed by journalism, mental health, public health, and suicide-prevention groups, along with the Annenberg Public Policy Center, say that reporters should consult reliable sources such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Source: Provisional data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Table: Annenberg Public Policy Center.

CDC data show that the months with the lowest average daily suicide rates are typically in the fall and winter: November, December, and January. In 2023, the last full year for which CDC data are available, December had the lowest average daily suicide rate – it was 12th among the months, and November was 11th. January came in 5th. The months with the highest rates were August (1st) and July (2nd).

This seasonal pattern for the suicide rate holds true in Australia, too. Romer last year conducted an analysis of average daily suicide rates over a dozen years in Australia. He found that the winter months in Australia had lower suicide rates, similar to the United States. Since Australia is in the southern hemisphere, the month with the lowest average daily suicide rate was June, which is the beginning of winter there.

In releasing the Australian data last year, Romer said, “This helps to explain the lower suicide rate we see here in December – it’s mostly due to the onset of the winter season. Psychologically, because of the shorter and gloomier days of winter in the U.S., we tend to associate them with suicide. But that’s not what happens in reality.”

Awareness for suicide crisis lines still lacking

Many countries have established national suicide prevention lifelines, but, at least in case of the U.S., APPC surveys have found that familiarity with the number is growing slowly, and still too few people know it. As of the September 2024 nationally representative panel survey, just 15% of U.S. adults are familiar with the suicide lifeline, up from 11% in August 2023. These are people who said they were aware that there is a suicide lifeline number and, in an open-ended format, said it is 988. “The help that can be found at the 988 helpline can only save lives if those in need and their loved ones and friends know the number,” Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center, said last month when this finding was released. “When 988 is as readily recalled as 911, the nation will have cause to celebrate.”

Source: Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania

14.12.2024