Mammography

Benefits: Are they a question of beliefs?

A panel of experts has recommended that existing programmes be phased out and that systematic screening programmes be replaced with systematic screening information that would give women the opportunity to make individual choices.

Report: Mark Nicholls

The move has been suggested by the seven-member Swiss Medical Board, an independent health technology assessment initiative, which, although sanctioned by some of the country’s leading medical bodies, makes non-legally binding recommendations.

The board initially published its recommendations in February, triggering a degree of opposition from cancer experts. However, the move was later discussed again by members of the board, which confirmed its position over winding down the breast cancer screening programmes in Switzerland on the basis that screening does not clearly produce more benefits than harm.

Two members of the Swiss Medical Board - Dr Nikola Biller-Andorno and Dr Peter Jüni – underlined the position with an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, stating: ‘We were struck by how non-obvious it was that the benefits of mammography screening outweighed the harms.’

With 5,400 women contracting breast cancer every year in Switzerland, and with 1,400 deaths from the disease, the board assessed the positive aspects of systematic mammography screening, such as earlier detection of tumours, alongside the potentially negative aspects such as excess therapy and psychological stress in the event of false positive results, as well as cost effectiveness.

It concluded that mortality rates from breast cancer can be reduced slightly by screening but added: ‘This desirable effect is offset by the undesirable effects: specifically with about 100 of 1,000 women with screening, erroneous results are produced, which lead to further investigations and, in part, to unnecessary treatments. Furthermore, the cost-effectiveness ratio is very unfavourable.’

This led the board to recommend that no new systematic mammography screening programmes be introduced; a time limit set on existing programmes and a call for all forms of mammography screening to be evaluated with regard to quality and for desirable and undesirable effects. They acknowledged criticism of the recommendations as contradicting ‘the global consensus of leading experts in the field’ but maintain they are looking at the issue from an unprejudiced standpoint rather than as part of past consensus-building efforts by specialists in breast cancer screening.

Medical ethicist Dr Biller-Andorno is Director of the Institute of Biomedical Ethics at Zurich University and Dr Jüni is an epidemiologist in the Department of Clinical Research at the University of Bern. Other board members are a clinical pharmacologist, oncologic surgeon, nurse scientist, lawyer, and health economist.

The Swiss Medical Board – appointed and sanctioned by the Conference of Health Ministers of the Swiss Cantons, the Swiss Medical Association, and the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences – has been reviewing mammography since the early part of 2013 and had concerns because they feared the debate was re-analysing out-dated trials, with none focused on more modern breast cancer treatments.

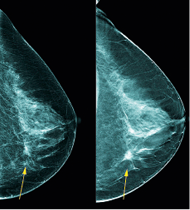

Drs Biller-Andorno and Jüni wrote: ‘The relative risk reduction of approximately 20% in breast cancer mortality associated with mammography, which is currently described by most expert panels, came at the price of a considerable diagnostic cascade, with repeat mammography, subsequent biopsies, and over-diagnosis of breast cancers – cancers that would never have become clinically apparent.’

They suspect there is ‘pronounced discrepancy between women’s perceptions of the benefits of mammography screening and the benefits to be expected in reality.’ Their editorial stated: ‘It is easy to promote mammography screening if the majority of women believe that it prevents or reduces the risk of getting breast cancer and saves many lives through early detection of aggressive tumours. ‘We would be in favour of mammography screening if these beliefs were valid. Unfortunately they are not, and we believe that women need to be told so.’

PROFILE:

Nikola Biller-Andorno, Professor and Director of the Institute of Biomedical Ethics at Zurich University, studied medicine at the University of Erlangen-Nuernberg as well as philosophy and social sciences at the University of Hagen in Germany, and between 2002-04 worked as an ethicist at the World Health Organisation. In 2004 she was appointed Professor of Medical Ethics at the Charité, Joint Medical Faculty of the Free and Humboldt University, Berlin, and a year later joined Zurich University as Full Professor of Biomedical Ethics. In 2007 she became the founding director of the Institute of Biomedical Ethics. The professor is a member of the Central Ethics Commission of the Swiss Academy of Sciences, a temporary advisor to WHO and deputy editor of the Journal of Medical Ethics. Her bioethics works have been published widely.

01.12.2014