Battling the bugs

National strategies to raise hospital hygiene standards

In terms of health politics, no hospital-related

subject is more explosive than hygiene.

However, although this reaction is common

across Europe, approaches towards tackling

nosocomial infections varies among our EU

countries. Karoline Laarmann reports from

Germany and Jane MacDougall from France…

GERMANY

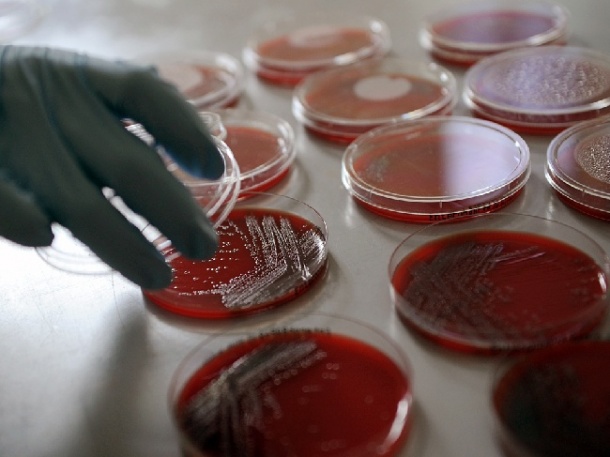

According to various estimates, every year between 400,000 and 600,000 patients in Germany fall ill with bacterial infections contracted in the hospital. The debate around nationwide standards for hospital hygiene began in 2010, after three infants died from infections caused by contaminated injections in the University Hospital in Mainz.

The Government recently passed a law on hospital hygiene to ensure better protection against infection through obligatory hygiene standards. However, the fact is that there are already numerous valid guidelines on a Federal and national level – the problem has been the lack of implementation to minimise infection risk. This was mainly due to a lack of staff and necessary budgets, complained Rudolf Henke, Chairman of the German medical trade union Marburger Bund: ‘No other industrial nation has a staff to patient ratio as low as Germany. This is why every hospital should have a hygiene commission and a hygiene commissioner.’ Therefore, he considers a national law, with new hygiene rules, is unnecessary.

The German Society for Hospital Hygiene believes the problem lies not with the legal framework but with the economic constraints: ‘Increasing cutbacks have resulted in 40,000 full-time nursing posts disappearing over the last ten years. Hygiene structures and procedures have been reduced or not been safely adhered to. Within the same period, an increasing number of patients have had to be looked after for ever shorter periods of time, with the corresponding respective risks for patients,’ says Barbara Nussbaum, Head of the Department for Hygiene for out- and in-patients and geriatric care/rehabilitation. The competent implementation of hospital hygiene on site can only be carried out by appropriately trained hygiene officers, the health expert adds. Therefore, a law on hospital hygiene only appears to be a potential way of tackling the problem of nosocomial infection.

Experts believe a much more essential role is played by the number of staff responsible for hygiene in hospitals along with the staff to patient ratio, as determined in the Netherlands by Dutch law. Germany’s neighbour is often quoted as an example, particularly when it comes to fighting multiresistant bugs. The MRSA rate there is <1%. ‘The intensive fight against multi-resistant bugs in the Netherlands began in the 1990s. Patients were immediately transferred to single rooms, isolated and then the pathogens were tackled. This prevented a spread at an early stage,’ explains Dr Jörg Hermann, Director of the Institute for Hospital Hygiene at Oldenburg Hospital, in an interview with the news programme tagesschau.de. Additionally, over the decades the Dutch have been much stricter about prescribing antibiotics. Nonetheless, due to the extensive structural and cultural differences, it is not that simple to transfer the Dutch hygiene strategies to the German healthcare system. In the Netherlands specialist doctors do not have their own surgeries outside hospitals. If you need a specialist there, you need to go to the nearest hospital. Furthermore, the way people deal with expert opinions is very different:

There is hardly any legislation on nosocomial infections in the Netherlands. Whilst the Germans back up their guidelines with legal texts, the Dutch completely rely on recommendations made by commissions of experts which are not queried by anyone but simply carried out.’ The prejudice against the Germans as a nation of bureaucratic sticklers over the letter of the law once again seems justified.

FRANCE

The Ministry of Health has had a national programme to prevent healthcare associated infections in place since 1995. The original aims were to reduce the number of nosocomial infections by one third and control the levels of multi-resistant bacteria by the year 2000. The programme was founded on four major axes: to reinforce organisation, create recommendations, train professionals and put structured surveillance in place. The emergence of patient support groups helped legislation that became applicable to all healthcare establishments at the end of the 1990’s. This legislation has been followed up and strengthened since the beginning of this century. Legal responsibility for nosocomial infections – defined as illness caused by a micro-organism after 48-72 hours of hospital admission, or 30 days following surgical intervention – is always with the hospital. Every institution through its Clinical Committee against Nosocomial Infections (Clin) and operational hygiene team (EOH) had to develop an action plan with two major components: surveillance and alert.

The RAISIN Network (National programme for early warning, investigation and surveillance of healthcare-associated infections) was at the heart of this strategy throughout the 2000s. This has led to standardisation in reporting techniques and data coordination so that a true picture of the nationwide epidemiology was formed. A potential weakness in the system is the composition of the EOHs, which varies from hospital to hospital. Depending on investment in the team, its effectiveness and commitment will vary. Teams may be composed of a doctor or pharmacist specialising in hygiene, a hygiene nurse and other personnel who may range from trained biohygiene technicians to secretaries depending on the size and activities of the establishment. To organise and finance these teams is expensive and has to be considered as a long-term investment for the hospital. Recently, in accordance with the HPST law of July 2009, the hospital’s medical committee (CME) took over Clin, and now responsibility for patient safety, which includes nosocomial infections, is in the hands of the hospital director and the president of the CME. The CME will define the establishment’s nosocomial infection programme as part of a wider remit of patient safety.

Other new measures include, since November 2010 the obligation for every healthcare institution to report a serious incidence of infection and completion of an infection check-list, with the patient’s contribution before any surgical intervention. A publicly available annual audit is also obligatory. The ICALIN (l’indice composite des activités de lutte contre les infections nosocomiales) score is a composite measure of performance against nosocomial infections. The incidence of MRSA, number of surgical infections and annual consumption of alcoholic hand rubs and antibiotics contribute to the value. Overall performance of the establishment is ranked from A to E (takinginto account size and number of beds) in each of three groups: organisation, means and action. A new society SF2H created in May 2010, which regroups all health professionals involved in hospital hygiene will now take charge of the organisation of scientific meetings and the creation of new guidelines and recommendations, a thorough survey of the problems still facing hospitals and an action plan for training, information and educationIn association with the National Programme for 2009-2013, the battle to reduce the incidence of healthcare associated infections will continue in France.

Electronic reporting in France

The external reporting of nosocomial infection has been regimented in France since 2001, Jane MacDougall reports, adding: but this has always been achieved by means of a paper trail from the health establishment via its coordination centre for the control of nosocomial infections to the Regional Health Agency, this latter organisation then informs the French National Institute for Public Health, l’Institut de Veille Sanitaire (InVS). In 2008, InVS launched an ambitious project to convert reporting of nosocomial infections to an electronic webbased system. This project, dubbed e-SIN for ‘electronicsignalement des infections nosocomiales’, aims to improve the management of report handling by all parties concerned and strengthen the commitment of health establishments to reporting incidences of nosocomial infection. To electronically report an NI, one of the hospital staff, preferably a member of the operational hygiene team in that establishment, has to connect to a secure internet site.

Once connected, they fill in their report and once it has been validated internally, publishing it makes it accessible to all the necessary bodies; the coordinating centre, Regional Health Authority and finally InVS. The e-SIN system enables all documents relevant to the case to be uploaded e.g. antibiograms, investigational reports etc.creating a comprehensive electronic dossier of the infection. The idea is that this paperless format will allow greater exchange of information between the authorities and the reporting establishment, so that the latter will be able to see the evolution of the information they provide and more easily follow the progress of their reporting. Depending on their role, each user will have access within the limits of their rights, to reporting histories and may anonymously interrogate the national data base, extract statistics or research previously reported similar experiences. The roll-out of e-SIN will help to reduce delays inreporting times, allowing the intermediary centres to give answers and possible aid to the health establishment concerned. Importantly, the constitution, a single, shared national database, will make analysis by InVS (approximately 1,500 individual reports per year) easier to identify potential trends in terms of emerging or recurrent outbreaks. The use of e-SIN will therefore facilitate the work of each of the players in the NI reporting system and ultimately improve patient safety.

Since 2008, a group comprising members of all the parties concerned has been in discussion with InVS to establish which data are the most relevant and important to its needs, so that the new electronic system can be as comprehensive and useful as possible. Once the format for reporting had been agreed, 2010 was dedicated to the first series of tests of the new system. This led to the initiation of a pilot phase, currently ongoing in several health establishments in eight different regions. This pilot phase will enable the system to be streamlined and modified to remove any potential bugs before the national launch of e-SIN, scheduled for this September. The complete switch from paper to electronic reporting is, so far, on target for the 1st January 2012. When completed, e-SIN will connect more than 10,000 users from all echelons of the healthcare system and will be the first web-based collaborative tool for reporting hospital-based infections. It is hoped that its success will be the precursor to the establishment of similar systems for the other medical situations that InVS monitors.

20.06.2011