Image sources: Bruno/Germany from Pixabay / Comfreak from Pixabay, Mashup: HiE/Behrends

Article • Discussing benefits and flaws

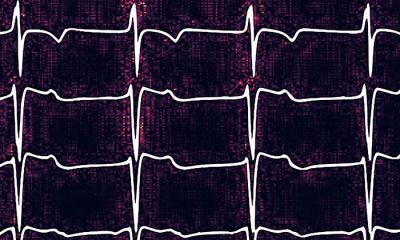

AI in cardiology: a marriage made in heaven – or hell?

The role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) – one of the most divisive issues in cardiology – was debated during a session of the European Society of Cardiology annual congress. Two leading experts argued the pros and cons of its use, exploring its benefits and advantages to cardiac care, as well as highlighting the pitfalls and shortcomings of AI, while underlining the need for clear guidelines and regulations for its use going forward.

Report: Mark Nicholls

The Great Debate sessions at the ESC 2021 online congress chose important – and controversial - subjects, with protagonists arguing their own viewpoint. In the discussion, “Great Debate: artificial intelligence in cardiology – a marriage made in heaven or hell?”, Professor Folkert Asselbergs outlined the benefits, while Professor Alan Fraser discussed a counter position. In opening the debate Chair Martin Cowie, Professor of Cardiology at the Brompton Hospital London and King’s College London, and chair of ESC digital health committee, said AI is a topic that most divides opinion among cardiologists.

Professor Asselbergs suggested that AI and cardiology cannot live without each other. It can support admin and keeping track of research developments, leaving cardiologists more time to focus on patients.

AI also has benefits in imaging, such as helping measure septal thickness in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) patients with much less variation than clinicians,” said Professor Asselbergs, who is Professor of Precision Medicine at the Institute of Health Informatics and the Institute of Cardiovascular Science, University College London. It can also extract data from a 12-lead ECG to predict atrial fibrillation or ejection fraction, and can be a screening tool, not only for experts or academic cardiologists but also in primary care where there is less experience in evaluating ECGs.

Looking further ahead, patients may use mobile devices with ECGs for diagnosis and prediction at home; machine learning-guided phenotyping could help in definitions of heart failure; and AI may be able to predict coronary artery disease from retinal screening in advances toward personalised medicine.

While doctors will not become obsolete, he said: “Machines are much more stable, less biased, have no conflicts of interest, and provide clearer information to improve health literacy.” But he stressed the need for more research and not being carried along by the hype, as well as highlighting issues of security, ethics, and quality standards, plus appropriate workforce training and the need for guidelines and rules (a kind of pre-nuptial agreement for AI).

Meanwhile, Professor Fraser argued that AI and cardiology is a marriage made in hell and instead of putting AI on a pedestal, “there is a need to look at its character flaws.” He suggested that computers and convolutional neural networks are “fundamentally stupid” as they only do what they are programmed to do. “The problem is that we use language that gives these programmes human characteristics of thought and decision-making, which they don’t have,” he said. “My second major concern about neural networks is that they are easily fooled.” With the huge amount of data, they can find patterns even if they do not exist and while showing correlations, they do not prove causation. He also expressed concern that a lot of development and implementation of machine learning is driven by technology rather than by a clinical question.

Professor Fraser said there is an assumption that better diagnosis will improve health, but he pointed to examples where prevalence of a disease can be increased by screening but mortality does not change. “We are over-diagnosing and medicalising the population and that is a risk with widespread use of very sensitive artificial intelligence tools,” added Professor Fraser, who also looked at studies comparing AI with human performance and remained unconvinced by several, while highlighting some where the human observer performed better.

He also underlined the need for sufficient evaluation of AI. “In conclusion,” he said, “are we ready for marriage? No. We are already engaged, that is clear, and there are many useful applications of AI but for complete trust and implicit faith and partnership, we are not ready. Computers can help us, but they should not replace our decision making. What we are awaiting is demonstration from these new methods of a beneficial impact on clinical outcomes.”

Application of AI in cardiology has a very bright future, however as a medical community we must be cognisant of avoiding pitfalls and minimising the risks

Mark Rabbat

Discussant Professor Nico Bruining from the Erasmus Medical Center’s Department of Cardiology in Rotterdam, Netherlands, asked questions of the debaters, while session co-chair Professor Mark Rabbat from Loyola University Medical Centre in Maywood, Illinois, said AI holds extraordinary promise for improving delivery of healthcare worldwide, but has its challenges. “Akin to all technology, AI can be misused and cause harm,” he continued. “One concern is that the use of AI could potentially worsen healthcare disparities. Regulatory and ethical guidelines are necessary. Application of AI in cardiology has a very bright future, however as a medical community we must be cognisant of avoiding pitfalls and minimising the risks.”

Profiles:

Folkert Asselbergs is Professor of Precision Medicine at the Institute of Health Informatics and the Institute of Cardiovascular Science, University College London and at University Medical Center Utrecht. He is also associate editor of the European Heart Journal, section digital health and innovation.

Alan Fraser is Emeritus Professor and consultant cardiologist at the University Hospital of Wales, visiting professor at the University of Leuven and Past-President of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging.

16.09.2021