A challenge for oncologists

‘The disease “cancer” is increasingly classified into sub-groups. Today, we are already dealing with a number of orphan diseases,’ says Professor Richard Greil MD, head of LIMCR at University Hospital Salzburg.

This is due to tumour heterogeneity, a major topic at the annual meeting of the German, Austrian and Swiss Societies for Haematology and Medical Oncology held in Austria this October, chaired by Professor Greil as Congress President.

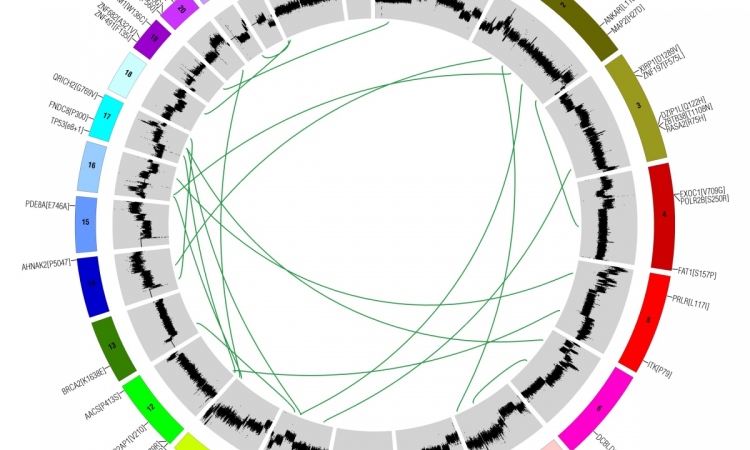

Generally speaking, tumour heterogeneity means that tumours differ depending on site, surrounding tissue and genetic predisposition of the patient. Thus, breast cancer is different from lung cancer and a brain tumour is different from a bone tumour. Cancer cell genes can have a high mutation rate but only a few of these mutations are so-called driver mutations, which are relevant for the development and evolution of cancer. While in lung cancer 180 of such mutations were found, in breast tumours only 30 driver mutations have been identified to date. ‘This explains why tumours evolve at different speeds and why they show different degrees of severity,’ Prof. Greil explains.

A patient’s age can be another important factor: the older the patient the higher the tumours’ genetic diversity from patient to patient. In brain tumours, for example, children show a much lower number of mutations in the cell genome than adults. ‘Therefore,’ he points out, ‘cancer is easier to treat in children than in adults.’

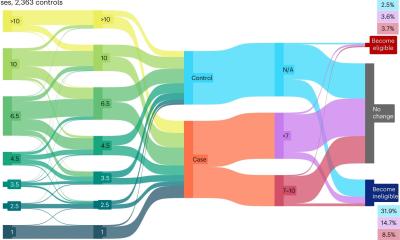

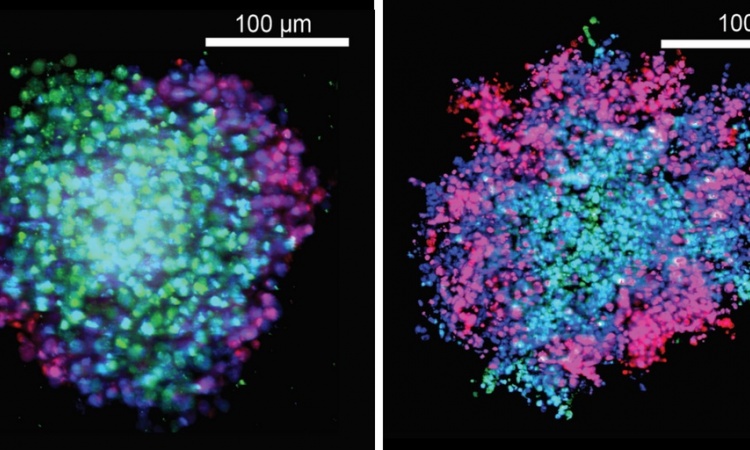

Tumour heterogeneity is even more complex: Genetic variation exists within individual tumours, so-called intra-tumour heterogeneity. ‘If you perform a biopsy at different tumour regions you can get significant differences in the gene expression profile,’ he underlines. The same holds true for a primary tumour and its metastases, he adds. ‘The specific environment of a tumour creates a specific selection pressure and influences the further evolution of a tumour.’ Moreover, cancer cell genotypes change over time. ‘In a targeted therapy we focus on a certain mutation but it may well happen that after two months the genetic profile of the tumour cells has changed and other driver mutations are dominating the development.

‘A single biopsy is not representative of a tumour and its metastases,’ he explains, referring to current research. ‘We need entirely new study designs and new diagnostic tools to get a picture of the genetic variation of a tumour. This is where we are entering a new era of molecular medicine. We have to gather sufficient information to get a complete picture of the genetic variation and how this variation is controlled.’ The Austrian oncologist has a clear idea where the development of new diagnostic tools could start: Every day three percent of the entire mass of a tumour’s DNA is released into the patient’s blood flow. New screening methods might help to cull relevant information from this process.

Profile:

Senior consultant and university professor Dr Richard Greil has directed the Third Medical Department for Oncology, Haematology, Haemostaseology, Rheumatology and Infectiology and

Head of the Laboratory for Immunological and Molecular Cancer Research (LIMCR), University Hospital Salzburg, Austria since 2004.

Before this, the Austrian oncologist headed the molecular-cytological lab and haematology out-patient services at the Department of Haematology and Oncology, at Innsbruck Medical University, where he had trained in medicine.

A member of many international medical associations, e.g. s the American Association of Cancer Research and American Society of Haematology, he conducts reviews for many international medical journals, such as Lancet Oncology. In Austria, he founded and is current chair of the Oncology Board that advises the Minister of Health on oncology issues and he was commissioned to design a national oncology strategy.

12.02.2014