Article • Medication testing

The birth of the amazing organoids

Professor Hans Clevers, researcher and group leader at the Hubrecht Institute in Utrecht, the Netherlands, invented the organoids, a ground-breaking new technique to grow new ‘organs’ and to test medication.

This year, his work was rewarded in the form of the prestigious Korber European Science Prize*, presented in Hamburg. At the Heinrich F C Behr-Symposium he discussed organoids and the individual therapy for colon cancer made possible by this significant development.

For years, Clevers has studied how cancer develops and what goes wrong at the DNA level. ‘Until 2007 it was thought that bowels do not contain stem cells. We discovered that they do, and even more, that they divide themselves every day. To make that visible, we added the DNA of fireflies in the stem cells of mice. And what happens in mice, also works for people. This discovery was a real breakthrough and it was a race against time to be the first to come out with this study. We – mostly – won this race, but it was also worth a lot to see that other researchers, who were on the same track, confirmed our research.’

The development of organoids

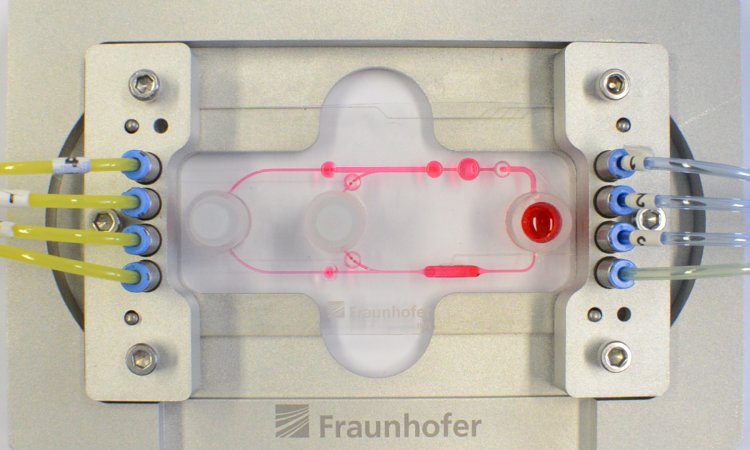

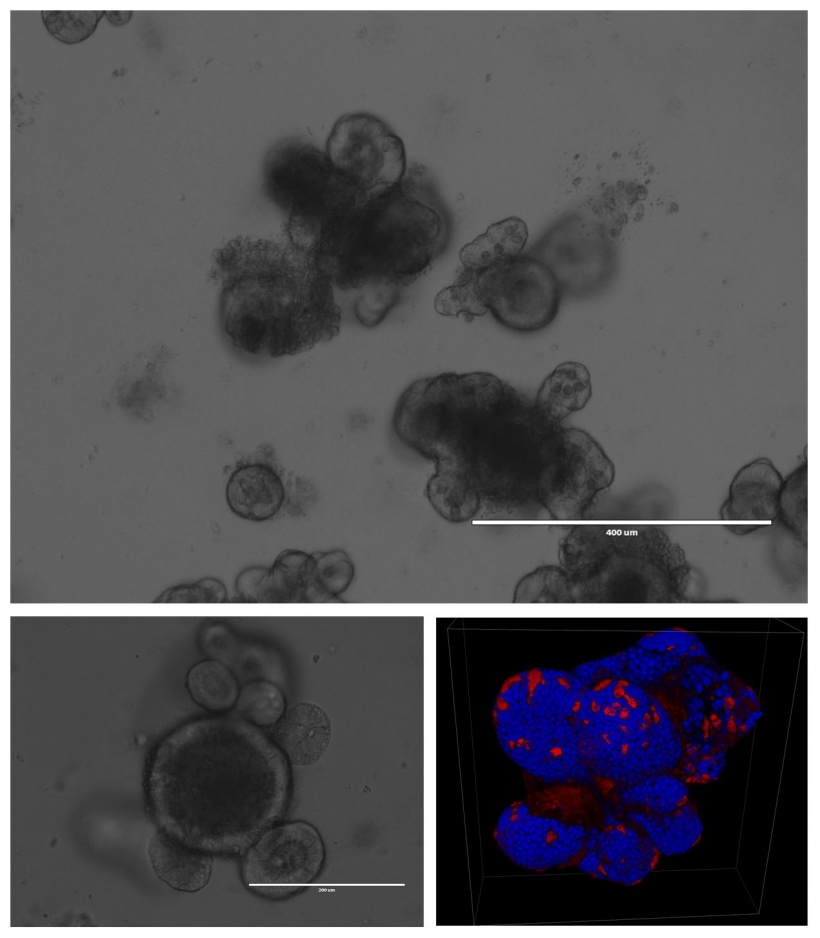

The discovery of stem cells in the intestines led to further investigation and, within two years, Clevers and team managed to grow a small intestine in a petri dish from a stem cell. The result is a new standard for the unlimited reproduction of adult stem cells, from which organs can grow in mini-size. Moreover, these ‘organoids’ contain all the cells that behave just as they do in the intestines, meaning that medication can be tested in real-life conditions.

Personal treatment method

Using organoids also leads to answers to questions such as how do cells work together; what they need from each other; what goes wrong to cause a particular disease, and especially how it can be solved. ‘With these so-called ‘Tumoroid’ studies, research is carried out on the patient’s disease. You harvest a few cells from the patient, out of which the organoids can grow.

‘This is far less stressful than several physical examinations. The result is that you can prove which medication will be most effective for this patient in order to provide him with personal treatment.’

Cystic fibrosis variants

Clevers, in close cooperation with Kors van der Ent and Jeffrey Beekman, from the Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital, proved the benefits of this technique. A Dutch patient named Fabian, aged 18 years, suffers a rare form of cystic fibrosis. ‘The medicine Ivacaftor was tested for people with cystic fibrosis who had emerged from the same DNA error.

Fabian was not eligible for the drug because it was not tested for the gene that causes his form of CF. With organoids, we showed that Ivacaftor would also work in him. So he was given the medicine after all and is now doing great.’

Dilemma and global training

However, the use of organoids also leads to a dilemma. ‘The cost of medications is high,’ Clevers pointed out. ‘You can still say “yes” if you can prove that medication will indeed help, but we can also predict with certainty when it does not. So do we have to refuse a medicine that people are entitled to have?’

Additionally, current regulations regarding the authorisation of new drugs are not yet adapted to the recent developments. ‘Therefore, we unfortunately cannot make any statements yet for colon cancer,’ Clevers explained. ‘The regulations also demand more testing on animals, whilst the use of organoids can diminish the use of animals in laboratories.’

Clevers is training lab staff worldwide in growing organoids. ‘In Hong Kong, for instance, influenza viruses were tested on pieces of lung removed during lung surgery. They needed to work very fast, because those pieces only remain good for four days. We have trained researchers from Hong Kong in our lab in Utrecht and now the technique is being applied there.

The Future

Clevers has not finished his studies. ‘The heart is still a virgin territory when it comes to the question of whether that organ has stem cells. In addition, the research into the application of organoids is still in progress. Yes, we can grow miniature organs and implant them in animals, but is that safe? Suppose you grow mini organ stem cells from a donor bank. Will you give the patient a new liver, but also perhaps a disease? Another step is the development of tailor-made drugs by pharmaceutical companies.’

His big dream, however, is the emergence of a liver bank, containing ‘freezers with pieces of liver that completely match the patient’s tissue and, further into the future, banks with other cultured organs.

Research goes much slower than you think, but currently ten times faster than anything we’ve ever experienced. So when I think of it, we will have that liver bank between now and ten years.’

* Awarded annually, the Korber Prize, worth €750,000, is one of the highest awards in medical world. With physics and biomedical sciences alternating every other year.

Profile:

Professor Hans Clevers MD gained his medical degree in 1984 and a PhD in 1985 at the University of Utrecht, the Netherlands. He carried out his post-doctoral work (1986-1989) with Dr Cox Terhorst at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard University, Boston. From 1991-2002 Clevers was Professor of Immunology at the University Utrecht and, since 2002, Professor in Molecular Genetics. Between 2002-2012 he directed the Hubrecht Institute in Utrecht. Additionally, between 2012-2015 presided over the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW). Since June 2015 he has directed research at the Princess Maxima Centre for paediatric oncology.

06.01.2017