Article • Biobank

Frozen samples are scientists’ gold

Our knowledge of causes and mechanisms of current and future diseases is on ice – not the perpetual ice of the polar caps but artificial ice. It is stored in biobanks at -80 to -160 °C.

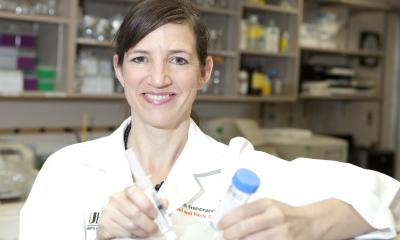

One of Europe’s leading biobanks is the Interdisciplinary Bank of Biomaterials and Data Würzburg (ibdw), Germany. Since 2013, biomaterials culled at Würzburg University Hospital are stored centrally for research purposes in a state-of-the-art facility. Any discipline can make use of the quality-assured bank content. ibdw is one of the first biobanks to implement the concept of ‘broad consent’ and to almost fully automate its processes. Availability of biomaterials will allow research on issues and diseases that are not even known today.

MEDICA EDUCATION CONFERENCE

Thursday, 17 November, 09.00 a.m. – 10.30 a.m.

Room: 17

Health IT: Modern clinical biobanking as a step towards European and global networking

Chairman: Prof. Dr. Roland Jahns, Würzburg

Broad consent

Since 2010, the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) has supported the establishment of centralised structures at five selected German locations to systematically collect liquid and solid human biomaterials. The University Hospitals in Aachen, Kiel, Heidelberg, Berlin und Würzburg were the first to implement centralised biobanks and the umbrella organisation ‘German Biobank Nodes’, founded in late 2013, will continue to develop the concept.

The purpose of a biobank is storage of patient tissue, blood and DNA samples donated for research. Prior to participating in a study, a patient signs a detailed consent form describing the research and the future use of the donated samples. ‘This broad consent is unique,’ says Professor R Jahns MD, cardiologist and director of the Interdisciplinary Bank of Biomaterials. ‘Drawing on our experience, a working group of the German Ethics Commission drafted a text template for non-specified storage and use of donor material for medical research purposes, since we don’t know today what research might be necessary 20 years down the road. The consent survives the death of the donor.’

Ethically and legally this is a balancing act that requires numerous accompanying measures. For example, the donor can withdraw consent at any time, research results must be presented to the donor and the public in a transparent and comprehensible way and, prior to the release of material that is not tied to a specific purpose, an Ethics Committee must approve the research project for which the material was requested.

Automation makes reproducibility

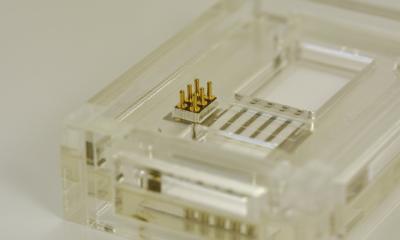

A further unique feature of the Würzburg biobank is the high degree of automation. It facilitates quality assurance and makes processes and results reproducible and comparable across locations. The OECD standard that defines handling of human biomaterials requires end-to-end documentation of the sample path, from sample taking to storage. ‘We document each and every step with a timestamp,’ Jahns explains. ‘On average we have ten to twelve timestamps per sample – completely automated. We are pioneering this process in Germany.’

The lack of reproducibility of research results prompted the Federal Ministry to intensify funding of centralised biobanks. Healthcare facilities have long been collecting blood and tissue samples in refrigerators. Any graduate student can take a frozen sample, thaw it, remove whatever he or she needs and refreeze it. In a modern biobank, a blood sample is separated into smaller 300 ml units prior to storage. These subsamples are usually sufficient to perform a triple assay that conforms to academic standards. ‘Such a smaller sample will usually allow serial triplets. Thus one blood sample will generate 10 subsamples. When a researcher requests a sample, only one sub-sample will be removed, the others remain at -80°C. It is a basic principle of a biobank to turn one large sample into several smaller ones.’

Keen protection

Currently, close to 200,000 liquid samples and 3,500 tissue samples are stored in Würzburg, allowing 1.2 million aliquots and 16,000 tissue sub-samples. Each sample tube is identified by an engraved unique barcode. 96 tubes fit on a rack, which is scanned prior to storage. The data are transmitted to the lab information system, which records the location of each tube.

Every piece of information is double-coded which means only the system itself knows where a certain sample is. ‘We can request a sample by entering a code. A virtual server and a double firewall make unauthorised access from outside pretty much impossible. The biobank is close to 100 percent safe.’

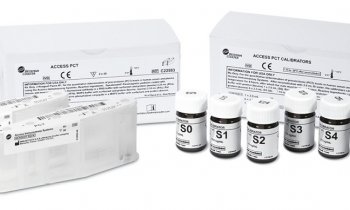

Biomarkers and molecular signature

The Würzburg biobank aims to support the research projects of the university’s medical school. Therefore, it collects a broad range of samples for oncology, cardio-vascular diseases and endocrinology.

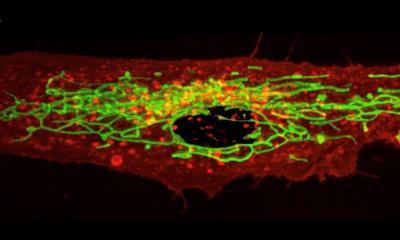

Samples from cancer patients usually encompass tumour core tissue, tumour margin tissue and non-tumour tissue. These samples are the basis for personalised therapies, since they allow examination of different tumour-specific molecular changes on the genetic level and molecular tumour signatures may be decoded.

Today, different mutations can be treated in a highly specific manner. Certain tumour DNA can be detected very early in blood – via a liquid biopsy – which can act as biomarker. ‘Biomarkers are also interesting for cardiologists. We take different samples over time from a patient with poor cardiac pump function and compare them looking for biomarkers that tell us how the heart will recover after a myocardial infarction. ‘The interesting point is that we collect prospectively but do the research retrospectively and still obtain valid results. Thus the samples are the scientists’ gold,’ Jahns explains.

Going forward, the number of biobanks to be funded in the context of the German Biobank Alliance will be doubled. The aim is for Germany to improve integration on the European level in the Biobanking and BioMolecular Resources Research Infrastructure (BBMRI) to be able to contribute significantly to research on rare and widespread diseases such as diabetes, hypertension or cancer.

Profile:

With a medical degree from the University of Würzburg, Professor Roland Jahns became a CEA Fellow in Sophia Antipolis (France) and DFG Fellow at the Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology in Würzburg. He specialised in cardiology in 2002 and received the GoBio Award of the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) in 2006. In that year he also became chair of the Working Group at Rudolf Virchow Centre for Experimental Biomedicine. He became a professor in 2008 and, since 2011, has been in charge of implementing the University Hospital Würzburg central biobank, becoming its director in 2013.

27.10.2016