Article • Disaster victim identification

Will CT scanning in post-mortem examinations mark the end of the scalpel?

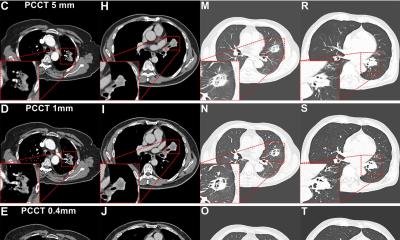

Post-mortem CT (PMCT) increasingly supports pathologists, radiologists and forensic investigators particularly in cases of gunshot fatalities, mass casualties, decomposed and concealed bodies, fire deaths, diving deaths, non-accidental injury cases, and road traffic deaths, in which CT can indicate a pattern of injuries.

Report: Mark Nicholls

In Dublin this August, the post-mortem (autopsy) technique was discussed during a forensic radiography workshop session, within the online ISRRT (International Society of Radiographers and Radiological Technologists) congress. Delegates heard a radiologist’s perspective; thoughts of a forensic pathologist, and about the use of the technique in Disaster Victim Identification (DVI).

Consultant radiologist Dr Ferdia Bolster pointed to a range of advantages in developing a PMCT service, such as dealing with bereaved families who are disturbed by the prospect of autopsy. ‘Some 90% of families will prefer a non-invasive alternative,’ he explained. ‘There may be cultural or religious objections and pathologists and doctors should try to minimise distress of autopsy if at all possible.’ With high autopsy rates in the UK and Ireland, there is a chronic shortage of pathologists, so PMCT may help in that respect.

Bolster, from the Radiology Directorate of the Mater Misericordiae University Hospital in Dublin, believes CT imaging is efficient. ‘It can be completed in less than 10 minutes, take radiologists less than 20 minutes to interpret the scan and CT also provides a permanent record,’ he explained. ‘Autopsy by its very nature is destructive because you have to dissect a body, but you can look at the CT scan at any stage in the future so there is a nice pre-invasive record.’

CT can help detect natural causes of death not detected at autopsy, such as brain bleeds, and spinal fractures can be seen in minutes.

In his personal experience, comparing CT scan data alone with no clinical details to subsequent additional data from the scene and toxicology, he found he was correct in pinpointing cause of death in 75 per cent of cases, compared with 90 per cent when full details were available. Bolster also outlined the role of CT in Covid-19 cases, particularly in protecting pathology staff when dissecting lungs for cause of death, or evidence of severe pneumonitis.

Posing the question of whether it spells the end of the scalpel, he believes that PMCT has not reached that stage, but pointed to techniques in Switzerland with a one-stop autopsy shop with CT scanner, body surface scanner and a robotic arm that will conduct CT-guided biopsy. However, he stressed, ‘It’s important to remember that radiology can only be a part of a post-mortem examination; we need to know the circumstances of death, the forensic scene, clinical findings, histopathology, toxicology, microbiology, and biochemistry. The cause of death is determined by all of these, so it is very much a team effort.’

What has been most useful from PMCT is seeing what’s in the body bag, or attached to the body, before we touch a body, and if there is any forensic evidence in with the remains

Sally Anne Collis

Dr Sally Anne Collis from the Office of the State Pathologist in Dublin gave a pathologist’s perspective on PMCT. ‘What has been most useful from PMCT is seeing what’s in the body bag, or attached to the body, before we touch a body, and if there is any forensic evidence in with the remains.’ There is, she suggested, a case for all forensic cases to have PMCT scanning, as happens in Australia.

Discussing cases in which she had been involved, Collis said the victims of a mass shooting in the north-west of England underwent CT scanning to offer an indication of the number of ballistic projectiles, where they were located and how they could best be recovered from the deceased. She also gave an example of man with a nail embedded in his head, which was not found until the skull was dissected, but would have been seen immediately with PMCT.

Whilst PMCT has advantages and disadvantages, she said, she is not comfortable with the idea of using PMCT as a complete alternative for formal post-mortem examination.

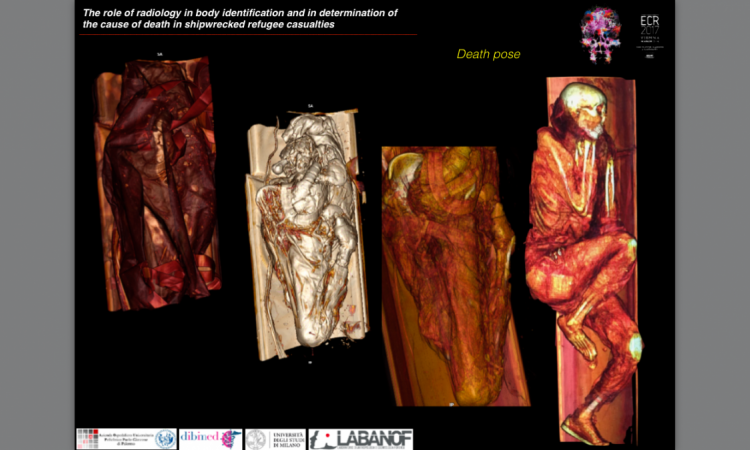

Victims of air crashes or major or natural disasters often suffer horrific traumatic injuries. Locating remains and identifying them requires meticulous and expert forensic investigation.

The use of PMCT in DVI was outlined by Forensic Radiology Consultant Jeroen Kroll from Maastricht University Medical Centre, who explained that DVI is where multiple individuals have died in a single incident, with their identity established through scientifically proven techniques. ‘It’s important to do DVI quickly and accurately for juridical reasons, and for relatives, so victims can be returned to their families,’ Kroll said. ‘It’s also important to keep in mind, in these times of terror attacks, that it can be a combination of criminal investigation and DVI process.’

From the retrieval of bodies, there are defined stages of the DVI process: of dividing victims into male, female, or unknown; looking at age; specific signs of primary identification, such as DNA, fingerprints, dental information and implants with unique serial numbers; and then secondary identification via personal descriptions, medical findings, tattoos, jewellery, wallets, shoes and clothing.

While X-ray has been used in the past in DVI, PMCT was first used extensively in the 2009 Victoria Bush Fires in Australia, in which 173 people died. The Interpol DVI guide now recommends the use of CT in the forensic radiology process. Under normal triage, a pathologist or anthropologist, together with a forensic police officer, would open a body bag for a visual victim assessment, but this can be conducted via PMCT without opening the bag.

CT was used in the investigations into the MH17 incident, where Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 was shot down over the Ukraine in July 2014, en route from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur. 298 passengers and crew were killed. Kroll was part of the forensic investigation team, which used a 16-slice mobile scanner to scan bodies while in sealed body bags. PMCT offers complete documentation of the body, and you can always go back to the complete CT and answer new questions,’ Kroll explained, and he stressed the importance of having an experienced team for the process.

Profiles:

Dr Ferdia Bolster is a Consultant Radiologist in the Radiology Directorate of the Mater Misericordiae University Hospital in Dublin and an Associate Clinical Professor at UCD (University College Dublin). His specialist interests include emergency and trauma radiology and forensic imaging.

Dr Sally Anne Collis is a newly-appointed State Pathologist in Dublin. She underwent forensic histopathology training in Liverpool and worked as a Consultant Forensic Pathologist in Edinburgh.

Jeroen Kroll joined the Forensic Radiology Unit at Maastricht University Medical Centre in 2009 and, as a forensic radiology consultant, provides forensic and legal input to police and prosecutors. He has also helped expand the use of forensic radiology in The Netherlands.

07.10.2021