© Thomas Fischer

Article • Predicting the future of imaging

What will ultrasound practice look like in 2030?

Rapid technical advances in ultrasound and increasingly tight healthcare budgets call for a change in ultrasound practice, experts explained in a session at the European Congress of Radiology in Vienna. Two experts presented possible models for the next two decades.

Report: Mélisande Rouger

Image source: ESR

Ultrasound has become less popular among young radiologists, according to Professor Paul Sidhu, a consultant radiologist in the Department of Radiology at King’s College Hospital, UK. ‘Trainees are less interested in performing ultrasound than CT or MR,’ he said.

In the UK, 90% of the ultrasound is performed by sonographers, nearly all of whom have undergone radiographer training, followed by a two-year apprenticeship in ultrasound, and often also a postgraduate diploma or MSc in ultrasound. This allows for many years of experience prior to independent practice. By contrast, radiologists have less formal training in ultrasound and tend to use the modality only in specialized settings, such as musculoskeletal, paediatrics or contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS). ‘Very few of the large teaching centres in the UK would have radiologists performing general ultrasound anymore,’ Sidhu said. ‘In district hospitals, they’re more likely to do general ultrasound once a week, but often only once or twice a week, contrasting with the sonographer’s daily practice.’

Unlike most European countries, sonographers in the UK perform both the examination and the reporting, but they’re accountable to radiologists, who are still responsible for imaging quality and safety. Ultrasound will thus become less of a radiology tool, Sidhu predicted. ‘It’s all going to have to change within 20 years,’ he told the audience. ‘You will get fewer trivial examinations being performed in the radiology-run ultrasound departments. A pleural effusion will be performed at the bedside by the clinician, just prior to the drainage procedure. There will be no need to take a patient to the ultrasound department.’

© Paul Sidhu

Finding the right balance

This scenario will be more cost effective for healthcare systems, which are increasingly under financial strain. ‘They can’t afford a doctor to perform all the ultrasound. The sonographer is less expensive than a radiologist, who has undergone years of medical training. Healthcare systems have to wonder if it’s efficient or necessary to have a physician perform all of the imaging examinations.’

A more sustainable scenario would be to have an ultrasound department run by the radiologists, but used by other practitioners of ultrasound, and staffed by doctors and sonographers. ‘The future will be a balance,’ Sidhu predicted. ‘It takes a lot of training to be able to scan properly. We will see that radiologists delegate more and more ultrasound to well-trained technicians.’ This model will expand slowly and will be initially hospital based, he added. ‘The radiologists will always ultimately be in charge because of their imaging background, but it will be a hybrid department where other specialists can use the equipment within the umbrella of the department, which will look at clinical governance, and safety and quality of the imaging,’ he said.

This is where the strength of radiology remains in retaining ultrasound, he explained. ‘Radiology should not lose it because it’s a modality that’s so ubiquitous and so useful as a point of care tool that you need it. But trying to convince the younger doctors to understand that is difficult,’ he concluded.

The German example

Image source: ESR

In Germany, some institutions have already established such interdisciplinary ultrasound centres to counter structural problems and high maintenance costs, according to Professor Thomas Fischer, Head of the Interdisciplinary Ultrasound Center of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany, who also spoke in the session. ‘The targeted and time-intensive training of ultrasound specialists, the personnel-intensive staffing of small ultrasound departments, and availability for on-call duty are urgent problems in many departments,’ he said. ‘Equipment fleets are maintenance- and cost-intensive, and in some cases outdated.’

In a recent article, Fischer and colleagues observed how institutions in Berlin, Munich, Regensburg, Rostock, and Trier set up and benefit from an interdisciplinary ultrasound centre. ‘They’ve been able to reduce the number of devices needed in a hospital and more efficient use of available equipment through bedside time optimization,’ he said. Establishing such a centre results in further potential for economic optimization. ‘The DEGUM multicentre study PRIMUS showed that hospital stay could be reduced from 8 to 5 days by using ultrasound within the first 24 hours in the emergency department,’ he said. ‘In some cases, inpatient admission can be avoided, and the number of outpatient treatments can be reduced. The effect on possible therapeutic consequences and targeted diagnostics is high.’

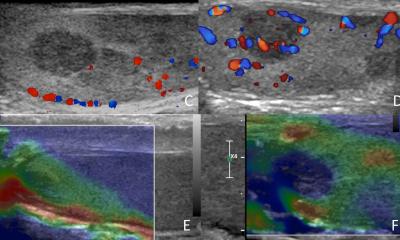

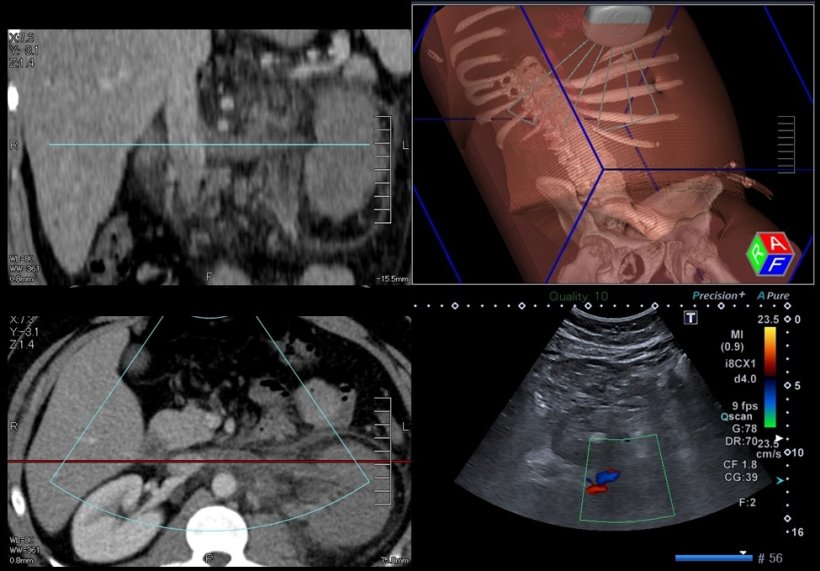

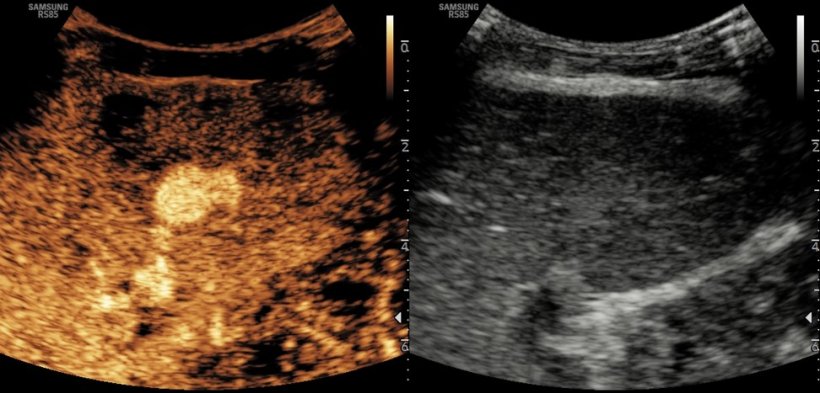

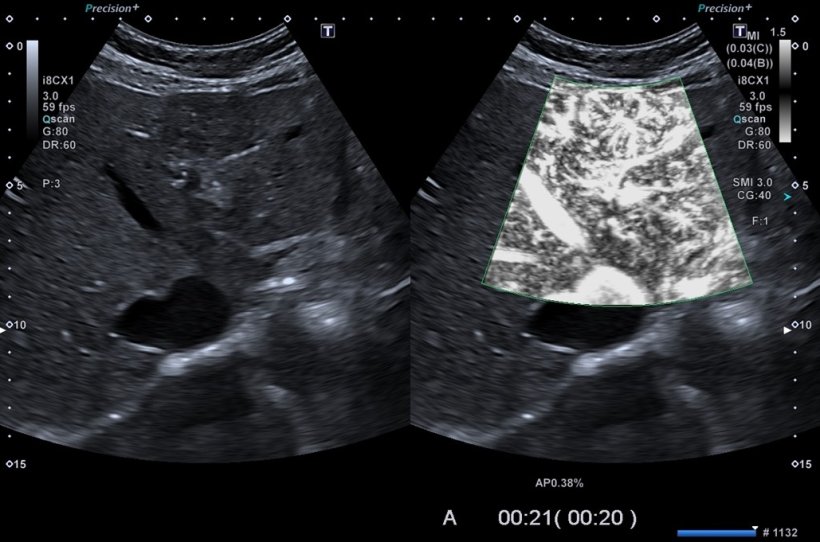

CEUS or image fusion for complex interventions, as well as training of younger colleagues can be centrally organized through the multidisciplinary experience available at such centres, Fischer noted. ‘Interdisciplinary centralization also allows standardization and better control of hygiene quality standards. The creation of an interdisciplinary image database based on standardized ultrasound protocols can significantly improve research,’ he said.

© Thomas Fischer

The challenge will be to coordinate the centralization of the modality with specific organ and disease related processes depending on the local conditions and requirements of the hospital. ‘Functional areas have been created in many departments in recent years and are spatially and organizationally oriented on the clinical pathway of the patient – for example, interdisciplinary outpatient breast cancer centres. A high volume of patients and examinations could limit the ability of an ultrasound centre to provide comprehensive sonographic resources,’ he concluded.

Profiles:

Paul Sidhu is professor of imaging sciences at King’s College London and a consultant radiologist in the Department of Radiology at King’s College Hospital. His research has focused on ultrasound and interventional radiology, and he has published extensively on many aspects of ultrasound, particularly in relation to male health and liver transplantation. Sidhu notably pioneered the introduction of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in the United Kingdom in 1996 and is recognized as an authority in the application of this technique in clinical practice.

Professor Thomas Fischer is Head of the Interdisciplinary Ultrasound Center of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany, where he founded the Ultrasound Research Laboratory. With a research focus on breast imaging, ultrasound contrast media, US/CT-MRI image fusion, rheumatic diseases, and prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment, Fischer has made important contributions to the development and improvement of new ultrasound techniques like elastography, image fusion, and ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy.

12.07.2022