Illustration: Karl-Heinz Nenning

Article • Man and machine

The radiologist as today’s centaur

Artificial intelligence (AI) continues to drive radiologists’ discussions.

Report: Michael Krassnitzer

Among them, Associate Professor Georg Langs, head of the Computational Imaging Research Lab (CIR) at the University Clinic for Radiology and Nuclear Medicine at the Medical University of Vienna, believes: ‘The evaluation of patterns in data from imaging examinations and clinical information about patients using machine learning will fundamentally changebour understanding of illnesses and their treatment as well estimation of their course.’

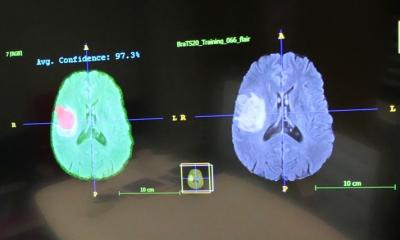

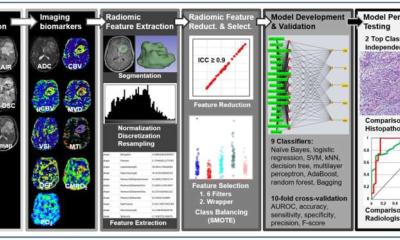

The Austrian computer scientist sees two major applications for machine learning – the form of AI by which a computer program learns from a mass of examples. First is the automated recognition of already familiar patterns, markers or signatures in image files that are diagnostically relevant, that also help to say something about the future course of an illness or, for example, how a certain patient will respond to a treatment. This also includes even the search for small tumours or metastases.

The second application – and in Langs’ view perhaps even more promising – is the discovery of new patterns, markers or signatures of diagnostic relevance that have yet to be identified. ‘Machine learning delivers really good results where we have come come to a dead end using conventional markers,’ Langs emphasises. A good example is the diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), a difficult to diagnose and rare lung disease. Here Langs‘ research group, in close cooperation with the lung fibrosis specialist Professor Helmut Prosch at the Vienna’s University of Medicine, identified six – among a total of 20 – patterns in CT lung images that consistently change in the course of the disease and can be applied to prognoses for the disease.

Recommended article

Article • AI in radiology

Augmented intelligence rather than artificial

Artificial intelligence (AI) will increase efficiency and improve quality as well as clinical outcomes – and thus strengthen rather than weaken the role of radiologists, said Dr Joon Beom Seo at ECR 2018. A spectre is haunting radiologists – the spectre of artificial intelligence. Is AI about to replace radiologists? Wrong question,’ declared radiologist Dr Joon Beom Seo, professor at the…

Changes in the brain

This Ping-Pong game between radiologists and machine learning experts works very well and leads to progress in the understanding of both sides

Georg Langs

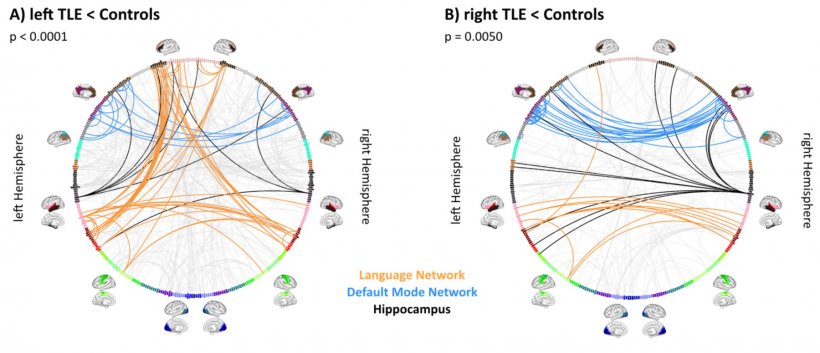

On the basis of MR images, the researchers studied how the functional connectivity architecture in the brain changes in patients with epilepsy or a glioblastoma. Although these diseases are based on focal lesions, the complex networks formed by the neurons change in the effected patients throughout the entire brain. ‘These are plasticity mechanisms that are candidates for markers with which structural changes can be recognised earlier,’ explained Langs. Initial findings indicate that this image analysis of brain function can be so sensitive that these mechanisms are recognisable even before a lesion is visible in structural MR images.

With all these applications, the aim is to create a prediction model that makes it possible to predict the future course of the illness. ‘However, if a treatment decision is made based on such a model, it must be clear what the underlying mechanism is,’ Langs emphasises. Machine learning is ‘agnostic’, as the computer scientist puts it: in a mass of examples it recognises a pattern that changes consistently and uses this – without regard for whether this pattern coincides with familiar physiological processes. If such a pattern is identified, then the computer scientist passes the ball back to biological research. ‘Meanwhile, this Ping-Pong game between radiologists and machine learning experts works very well and leads to progress in the understanding of both sides’, Langs points out.

AI is a black box

Computer scientists are also trying to manage the so-called ‘Black Box problem’ – that it is impossible to trace from outside how a program based on machine learning arrives at its results. ‘In the past two years efforts have been intensified to develop methods for tracing the prognosis back to the source,’ Langs reports. Thus, the following question is answered: What is presented in the data that leads to a diagnosis or a correct prognosis? This information is also forwarded to the physicians so that they can investigate which physiological processes are behind everything. These efforts are summarised by the maxim ‘Explainability’.

‘The radiologist is increasingly becoming the data integrator and interpreter of subtle patterns in the diagnostic process – and machine learning is a powerful tool for this,’ Langs explains when asked about the future of radiology, given the numerous AI applications in the field. ‘Certainly, radiologists will not be replaced by machines but their work will change. In the future, they will be able to concentrate on more complex questions.’

Profile:

Associate Professor Georg Langs (Dipl-Ing) studied mathematics and computer science in Vienna and Graz. Following years of research at the Ecole Centrale in Paris and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the USA, the computer scientist returned to Vienna’s Medical University (MedUni Wien), where today he heads the Computational Imaging Research Lab (CIR, www.cir.meduniwien.ac.at). He also teaches at the University of Vienna, is a reviewer for several international specialty journals, including IEEE Transactions on Pattern Recognition and Machine Intelligence and IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, and is the author of numerous technical articles.

26.02.2019