The biology of cancers

By Professor Gilles Favre, lecturer and researcher at the Cancer Institute Claudius Regaud, Inserm-Université Paul Sabatier, Toulouse, France, and Scientific Coordinator of JIB 2009 *

Cancer research is progressing rapidly. For a large part, biology contributes to its most significant advances, which aim to renew the whole model of cancer care.

The use of systemic therapies presently remains too empirical. This situation leads to the under-treatment of patients affected by aggressive cancers, while patients affected by slow progression cancers are being over treated. Among all these patients, only a proportion will meet with a real clinical benefit. But, the side effects of treatments are deleterious to both populations of patients.

Today, the most recent developments in molecular biology, molecular diagnostics and targeted therapies are progressively re-orienting the treatment of cancers from a traditional ‘trial – failure – trial’ scheme to personalised therapies: to bring the right molecule, at the right dose to the right patient. However, to realise this objective means performing markers have been validated to

• distinguish patients with aggressive forms of cancers from diseases that will develop slowly

• predict prospectively the response or the resistance to different therapies

• And, finally, to identify patients likely to develop toxic and severe effects to a specific treatment.

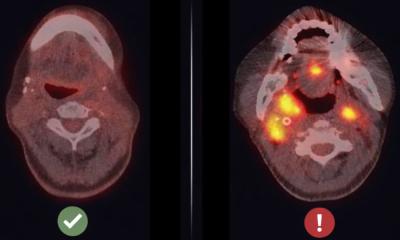

Molecular analysis of tumours

The molecular analysis of tumours, commonly of the primitive tumour, has recently been positioned as a standard for the discovery and clinical use of biomarkers, with undeniable success, but also with limits. In some cases, one can surprisingly predict the evolution of a disease, or therapy efficiency, on the simple record of the molecular profile of the tumour realised at a given time of the disease, which, by definition, is to evolve.

Serum analysis complements tumour analysis

Serum analysis represents a particularly important issue in the very history of the disease, as serum is an essential vector of disease dissemination. The permanent interaction, either physiological or pathological, that serum maintains with the other tissues of an organism makes it a second site for markers characterisation. Its accessibility enables sequential analysis of biological parameters, which reflects the dynamics of the tumour pathology.

Blood substitution

The idea of using blood as a substitution site to the solid tumour is not new. Here, indeed, it is of great relevance to distinguish solid tumours from malign haemopathologies. Hence, for many years, the latter have benefited from cellular and molecular serum markers, which have largely transformed the coverage of oncohaematology for patients.

Solid tumours

Oncobiology has long been confined to the analysis of traditional tumour serum markers and has remained of little significance in cancer care. However, biologists’ and clinicians’ most prospective works have permitted very precise definition in the possible use of cancer biomarkers and some of these have become indisputably efficient in the conduct of different cancer therapies or in disease follow-up.

New cellular concepts and new molecular technologies

These have placed oncobiology at the forefront of cancer research. Proteomic profile analysis, the search of genetic anomalies in circulating tumour cells, the characterisation of genes expression regulating micro-ARN, and the analysis of circulating DNA mutations represent the many leads being explored, which will be presented in the JIB scientific programme. New technological concepts should be associated with the dynamics of these scientific tracks: from fluidics applied to cellular separations to molecular analysis’ nanotechnologies.

The success of these researches lies within essential interdisciplinary collaborations between clinical biologists, molecular biologists, oncologists, pharmacologists, engineers and the diagnostics and pharmaceutical industries.

From hospital to home care

Finally, the medical care of cancer patients, from treatment to a lifetime follow-up, will relocate increasingly from the hospital to home. New analysis markers will then have to depart from hospital laboratories and enter independent medical biology laboratories. Consequently these laboratories, which tend to generalise in molecular techniques, will take a more active part in the cancer treatment chain.

They should position themselves as prior actors in the emerging personalised medicine model and thus ensure the necessary transfer of science’s best performing techniques closer to patients.

* JIB 2009 ‘International Journeys of Biology’, the annual meeting for European medical biology professionals organised on the initiative of the Syndicat des Biologistes (SDB). This year’s meeting took place in Paris in early November. Details: www.jib-sdbio.fr/

16.11.2009