Seeking new diagnostic options against TB

What's on the horizon?

Tuberculosis (TB) is a growing global pandemic caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria. Although TB is curable, every day 5,000 people die from the disease, usually because it is undiagnosed or diagnosed too late. Infection is acquired through exposure to an infectious patient with TB of the lungs and, in most cases, is controlled by the immune system with the infection lying dormant. This state, known as latent TB infection (LTBI), causes no symptoms and is not infectious - but latently infected people have a 10% risk of progressing to active symptomatic TB disease.

In young children, HIV-positive people and those with suppressed immune systems (due to concomitant illness or immunosuppressive medication) this risk is greatly increased. Because of the rapidly spreading HIV epidemic in Eastern Europe, Central Asia and Sub Saharan Africa, the number of TB/HIV-co-infections is expected to keep rising in these regions.

The tools for diagnosing TB infection and disease, such as the Tuberculin Skin Test (TST) and sputum smear microscopy and culture, are 80-100 years old and they fail in more than 50% of cases in the patient groups at the highest TB risk. Therefore, new and more effective diagnostic methods are urgently needed.

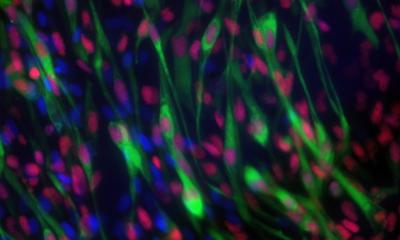

The T-cell interferon gamma release assay is the diagnostic tool with the highest currently-available sensitivity and specificity for detecting LTBI. This rapid blood test was invented about 10 years ago by Professor Ajit Lalvani, Chair of Infectious Diseases at the National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, and is now recommended by national guidelines in almost all developed countries. Prof Lalvani heads a world-leading multidisciplinary research group integrated with Britain’s largest clinical TB service in the heart of Europe’s TB capital, London. ‘T-cell-based blood testing for latent tuberculosis infection is not only the first practical advance in the area of TB diagnostics for over 100 years, it is also the first assay of its kind ever in medicine,’ he told us. ‘In Europe, improving diagnosis and preventive treatment of LTBI is the main priority as it effectively prevents latently infected people from progressing to TB disease. In the developing world, improved diagnosis of LTBI will be important in young children and HIV-positive people, but the public health priority is still to improve prompt diagnosis and treatment of active TB.

‘During latent TB infection, the body is infected with only a few dormant bacteria but the T-cell response detected by the assay I developed serves as an amplified signal for the presence of these organisms, which cannot be directly detected. This gives the assay higher diagnostic sensitivity than the TST, including in HIV-infected people, and it is also more specific as it is not confounded by prior BCG vaccination – an important consideration since most of the world’s population is BCG-vaccinated,’ Prof Lalvani explained.

There are two types of commercially available T-cell interferon-y release assays. How do they differ? ‘The whole-blood enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) takes less time to process in the lab because you don’t have to separate out the white cells. It’s also significantly cheaper. The enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISpot) in return has higher diagnostic sensitivity.’

False negative results with the test are not common but they can occur in immunosuppressed people. A test with still higher sensitivity is therefore desirable and, according to Prof Lalvani, could soon be available: ‘Having brought the revolutionary new paradigm of T cell-based diagnosis to the clinic, the rate of translation of scientific advances from the research bench to the patient’s bedside is increasing rapidly, as we incorporate the latest advances in immunology and bacterial antigen discovery into next-generation tests.

‘We have already clinically validated the first of our next-generation tests, called ELISpotPLUS. By incorporating an additional key antigen, we significantly enhanced the diagnostic sensitivity without compromising specificity. When these higher levels of diagnostic sensitivity are brought into routine clinical practice, realistically we could, for the first time, reliably exclude the possibility of TB infection when evaluating patients with suspected TB; this would enable rapid triage of patients in less than 24 hours, which will save costs and improve hospital infection control.’

What other developments may be expected? ‘By applying our latest immunological discoveries we are also developing new approaches to monitor the effectiveness of TB treatment and to distinguish between LTBI and active TB. ‘As you’d expect, the immune system reacts differently depending on the state of infection in vivo; the trick is to harness these immunological changes and measure them simply in the clinic so that our next-generation diagnostic tests can give us much more clinically and biologically relevant information about our patients,’ the professor explained, adding: ‘It’s an exciting time for immune-based diagnosis of infectious diseases.’

01.03.2009