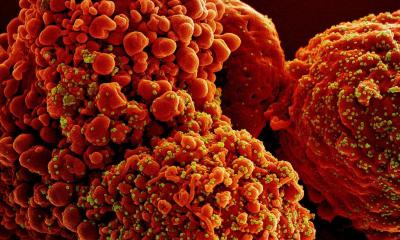

Ebola

Seeking best practice

On 29 July, Dr James Ritchie was attending the American Association of Clinical Chemistry’s annual conference in Chicago when he received the call that a physician and missionary worker, who had been in West Africa, were headed to Atlanta’s Emory University Hospital.

Report: Lisa Chamoff

Nearly four months later, Ritchie, an associate director of the core and toxicology laboratories at the hospital, shared some of the lessons he and his staff learned in eventually treating four ebola patients. During a webinar hosted in November by the American Association of Clinical Chemistry (AACC), he explained: ‘Laboratory testing … was what really made the difference between the treatment they would received in the U.S. compared to the treatment they would have received in West Africa, where they were stationed.’

Emory University certainly had a leg up in handling the virus. The facility’s Serious Communicable Disease unit was established in 2003, after the facility was approached by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, also based in Atlanta, about providing a place where workers could come if they contracted a virus in the field, or had an accident at one of their laboratories.

Lab staff was comprised of four different medical technologists, all point-of-care (POC) coordinators who trained every six months. Ritchie said they used a completely isolated facility instead of the main lab for testing, out of an ‘abundance of caution’, and because it was available, though he notes that a dedicated lab is not required when working with ebola.

Protective clothing and an observer’s surveillance

Of course, caution was also taken when interacting with the patients. Lab workers, as well as nurses and doctors, would first go into a clean anteroom, put on paper scrubs and plastic shoes in a locker room and then don protective gear before going into the patient’s room. There was always a safety person, who was nearly suited up, looking on in case there was an accident. After leaving, the visitor would remove their gloves, wash their hands and doff their PPE in a special ‘hot area,’ before going into the locker room to shower. Even with so much already in place, the facility needed to be flexible. In the lab, with doctors requesting more and more tests, they had to expand from one particular chemistry rotor to a whole family of chemistry rotors. Something Emory lab workers also found useful was a fully automated PCR instrument from BioFire Diagnostics, which was used a lot to monitor respiratory, GI and blood culture infections to rule out other diseases the patient may have had.

Communication was the key in coordinating testing, Ritchie said. At Emory, the lab technicians started out taking verbal orders from the physicians, but after a lot of miscommunication, with things getting done that weren’t ordered and vice versa, they switched to a paper requisition that the nurse or doctor filled out. There was a team meeting every morning to review plans and protocol and there were many open forums and town hall meetings.

‘It’s very important that every member of the team knows what’s expected of them and what’s going to be happening during the day,’ Ritchie pointed out. Staff in the area also had their temperature taken twice daily and had to answer questions about symptoms, which continued for 21 days after their last shift in the unit via the web. As the first community hospital in the United States to admit an ebola patient, staff at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, Dallas, also found that communication was important in handling the virus. Beverly Dixon, medical director in the hospital’s department of pathology and laboratory medicine, offered a list: ‘Communication to the nurses to control times of testing and draws and allowable testing; communication to the doctors who would like to order everything in the EMR lab catalogue, which can’t really be done and turns out it isn’t necessary anyway; communication to staff in a manner that allows you to post lab menus so that they could know exactly what can be done.’

When the patient first came to the hospital, she said, they didn’t know he had ebola and the facility handled the specimens in the standard way, with ‘no negative outcomes.’

More stringent decontamination of instruments

The second time, to rule out other illnesses, they ran the specimens using standard universal precautions, but with more stringent decontamination of instruments. There were two workers furloughed for 21 days, who were found to not have used standard precautions properly. Ultimately, 38 people were monitored.

The facility did switch from standard universal precautions to using much more stringent PPE, which made staff feel much safer in handling the specimens, she said. Dixon advises labs to perform a risk assessment to figure out appropriate protocol and equipment for that facility. She recommends a template for public health risk assessment for the ebola virus that is available on the Association of Public Health Laboratories website.

Dixon also recommended taking a mock specimen and running through the handling process. ‘During that observation, you’ll see things you would never have thought of while you were sitting there at a desk versus walking through the actual procedure on an instrument with a mock

specimen.’

Handling waste and shipping specimens

Something Emory wasn’t prepared for was the amount of medical waste the patients generated. Ritchie said two patients generated a total of 350 bags, or about 3,000 pounds, of medical waste.Shipping specimens is also a big issue. While Emory University Hospital was lucky enough to have the CDC down the street, laboratories do need to plan a shipping strategy. Peter Iwen of the University of Nebraska Medical Center, noted that the facility found it challenging to arrange shipment of ebola samples with a courier, and ultimately ended up spending $1,900 per sample. ‘This was not an easy thing to do,’ he explained.

Samples are required to be shipped as Category A infectious substances, which meant the person packaging the sample and the courier had to be certified. Once you have an ebola positive patient, the CDC will provide guidance, but the shipping issue will likely be a challenge. ‘You need to have this relationship with your public health laboratory,’ Iwen said. ‘You need to work out details of how you’re going to get samples from a patient that might be in your emergency department, who you are trying to screen or rule out ebola virus infection.’

19.12.2014