News • Exploring the role of colibactin

Research links bacterial toxin to colorectal cancer

Exposure during childhood to a bacterial toxin could be triggering an epidemic of colorectal cancer among young people.

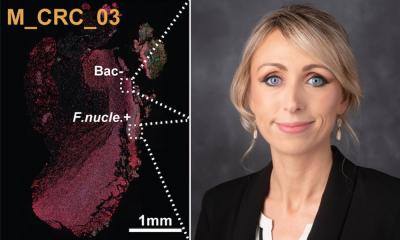

Image source: CNIO/Laura M. Lombardía

This is according to new insights published in Nature by an international team led by the University of California at San Diego (USA) and whose first signatory is Marcos Díaz Gay, head of the new Digital Genomics Group at the CNIO (Spanish National Cancer Research Center), hired under the Building Generation AI program of Generation D.

Colorectal cancer is considered an aging-associated disease, but its incidence in adults under the age of 50 has approximately doubled over the past 20 years in several countries around the world. Research points to the bacterial toxin colibactin as a possible culprit for this increase in early-onset colorectal cancer.

Colibactin is a toxin produced by some strains of Escherichia coli – one of the many bacteria that populate the colon and rectum – and has the ability to alter cell DNA. The now-published finding finds that exposure to colibactin in early childhood imprints a distinct genetic signature on the DNA of colon cells.

The result is based on a computational analysis of genetic mutations, and is the first to demonstrate a substantial increase in colibactin-related mutations in colorectal cancer cases under the age of 50. It therefore immediately raises questions that the authors cannot yet answer, such as how infection of colibactin-producing bacteria occurs and how to prevent or combat it.

If someone acquires one of these driver mutations by the time they’re 10 years-old, they could be decades ahead of schedule for developing colorectal cancer

Ludmil Alexandrov

The authors analyzed 981 genomes of colorectal cancer patients from 11 countries. The results show that colibactin leaves behind specific patterns of DNA mutations, patterns identifiable as true ‘mutational signatures’. These signatures are 3.3 times more frequent in adults under the age of 40 than in those diagnosed after the age of 70. In general, colibactin signatures are especially prevalent in countries with a high incidence of colorectal cancer in young people. “These mutation patterns are a kind of historical record in the genome”, says Ludmil Alexandrov of the University of California, San Diego, and lead author of the study. “They point to early-life exposure to colibactin as a driving force behind early-onset disease.”

The implications are highly relevant. If the current trend continues, colorectal cancer could be the leading cause of cancer death in young adults by 2030. Until now, the cause of this increase was unknown. Young people with colorectal cancer do not usually have a family history and have few known risk factors, such as obesity or hypertension, which has led to a search for possible causes among likely environmental carcinogens or microbial infections. “When we started this project, we weren’t planning to focus on early-onset colorectal cancer,” said Marcos Díaz Gay. “Our original goal was to examine global patterns of colorectal cancer to understand why some countries have much higher rates than others. But as we dug into the data, one of the most interesting and striking findings was how frequently colibactin-related mutations appeared in the early-onset cases.”

Díaz Gay joined the CNIO in November 2024 as a researcher member of the Building Generation AI program, in the framework of the Generation D initiative. He came from Alexandrov’s group, where he was a postdoctoral researcher. According to his results, the deleterious effects of colibactin start early on. Colibactin-associated mutations arise at an early stage of tumor development, which is consistent with previous studies showing that such mutations occur in the first 10 years of life. “If someone acquires one of these driver mutations by the time they’re 10 years-old,” Alexandrov explains, ”they could be decades ahead of schedule for developing colorectal cancer, getting at age 40 instead 60.”

For this researcher, the new study “provides strong support” for the hypothesis that colibactin-producing bacteria could be silently colonizing the colon of boys and girls, initiating molecular changes in their DNA and paving the way for colorectal cancer long before the onset of symptoms. He stresses however the need for further research to “establish causality”.

The study is part of the Mutographs of Cancer – Cancer Research UK Grand Challenge Project, a broad collaboration of the University of California, San Diego, the Wellcome Sanger Institute and the International Agency for Research on Cancer that looks for patterns of mutations caused by environmental agents, such as UV radiation, bacterial toxins, tobacco and alcohol. As Díaz Gay explains, “each factor leaves a distinct genetic fingerprint in the genome, a unique mutational signature that can help pinpoint the origin of certain cancers”. Research into these mutational signatures in thousands of cancer genomes is making it possible to identify hitherto unknown carcinogens.

Recommended article

Article • Awareness

Focus on cancer

From solid tumors to metastatic carcinomas and leukemia: cancer is among the most common causes of death. Keep reading for latest developments in early detection, staging, therapy and research.

The authors outline the questions they would like to address in the next phases of this research:

- how are children exposed to colibactin-producing bacteria and what can be done to prevent or mitigate that exposure?

- are there diets or lifestyles more conducive to colibactin production?

- how can people find out if they already have these mutations?

Whether the use of probiotics could safely eliminate harmful bacterial strains is already being studied, and early detection tests that screen stool samples for colibactin-related mutations are being developed.

The research published in Nature also finds that certain mutational signatures are particularly prevalent in colorectal cancers in some countries, notably Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Russia and Thailand. This suggests that local environmental exposure may also contribute to cancer, although it is not yet known to what factors. “It is possible that the causes vary from country to country,” Diaz-Gay says. “This opens the door to region-specific prevention strategies.”

Alexandrov further points out the conceptual shift that these results represent: many cancers may have their origin in environmental or microbial exposures early in life, long before diagnosis. “This changes the way we think about cancer. It’s not just about what happens in adulthood, but also in the first decade of life, perhaps even in the early years.”

Source: Spanish National Cancer Research Center

29.04.2025