Protein test instead of cystoscopy

A recent study from the Heidelberg-based company Sciomics, a spin-off from scientists from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), has presented an advanced method to predict the recurrence of bladder cancer after surgery. The method, which can help avoid frequent cystoscopy examinations in a majority of patients, is based on an analysis of the protein composition of cancer tissue obtained during surgery.

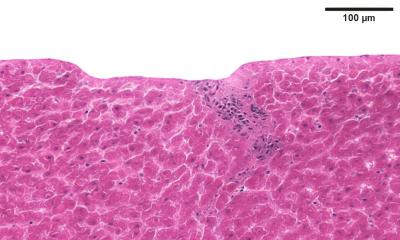

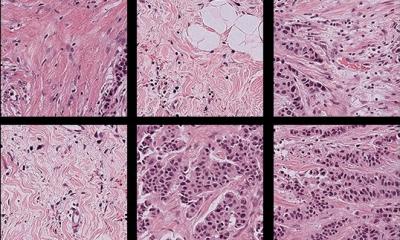

The test detects proteins relevant to cancer that are suspected to promote recurrence, thus facilitating a prognosis for the disease. Approximately 60 percent of patients suffering from bladder cancer that has not yet spread to layers of muscle tissue in the bladder have a recurrence of the disease within five years after surgery. “These patients must have a cystoscopy every three months,” says Dr. Christoph Schröder, proteome researcher at the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) and CEO of Sciomics GmbH. “For many people this is an unpleasant examination, and it is also costly. We wanted to find a way to make things easier for the patients and save costs at the same time.” In a recent study, the scientists compared cancer tissue obtained from patients who had remained cancer-free within five years after their surgery with tissue from patients who had suffered a relapse. Of the 725 proteins that were analyzed, over a third exhibited significant differences between the two patient groups. “We identified 255 proteins that appeared at either much higher or much lower levels when comparing the samples,” said Schröder. This enabled the researchers to classify the cases into distinct groups. They selected 20 of the proteins whose behavior could be used to predict the chances of a recurrence very precisely.

“The results are promising. We will now extend the study to several hundred patients in hopes of confirming our results,” says Dr. Jörg Hoheisel, head of division at the DKFZ. However, Hoheisel says, the development of a clinical application will require quite some time; the cases must be monitored for at least five more years.

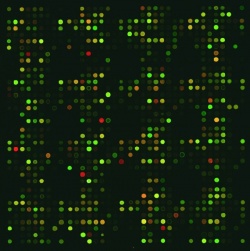

To carry out the study the scientists used antibody microarrays, which can also be simple and effective diagnostic tools. One type of microarray attaches thousands of antibodies, each of which is capable of binding to a specific protein, into rows on a solid surface. When the scientists pour a solution of proteins on the array, any of the molecules bearing a binding site that is complementary to one of the antibodies will attach itself, leaving it caught in the researchers trap. A single array can hold a vast number of spots, permitting the detection of thousands of antibody-protein combinations in a single experiment. Subsequently, the array is scanned by a laser to make the proteins visible through a color (fluorescence) reaction. This allows scientists to determine which proteins are present in a sample and the quantities at which they are produced.

Scientists use microarrays to screen for differences in protein expression – between different types of patients, or to compare healthy and diseased tissue. This permits the development of distinction criteria, or biomarkers, that can be used to make an initial diagnosis, predict how a disease will progress, or choose the most promising treatment. Microarrays also deliver important results for the pharmaceutical industry in the development of compounds for new drugs.

Thus the use of antibody microarrays extends beyond cancer-related research to making diagnoses and prognoses for individual patients. “The method can also be used to detect other pathogenic alterations, sometimes at very early stages,” says Schröder. “A previous study has shown that it can be used to diagnose different types of pancreatic cancer. And an ongoing project suggests that it can be used to predict whether a patient will experience acute kidney failure in the aftermath of cardiac surgery or a lung transplant, before surgery is ever performed. It’s crucial information to have because this risk may be up to 50 percent,” Hoheisel adds.

25.06.2014