PET/CT-specific radiopharmaceuticals for diagnosis and therapy

The multiple benefits of PET/CT are undisputed – one being the fact that radiopharmaceuticals, which are used at pico and nano levels – are not toxic.

Newly developed radiopharmaceuticals are highly specific and thus allow precise molecular characterisation of the tumour in question. Today, however, not only pharmaceutical companies but also academic research institutions produce these powerful substances. Ludwig Maximilian University (LMU) in Munich has operated its own radiopharmaceutical production lab since August 2013.

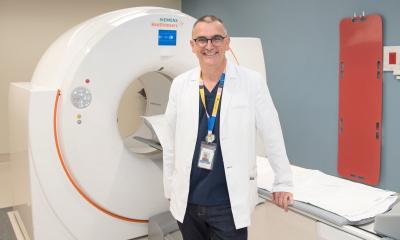

Professor Dr Peter Alexander Bartenstein, Director of the LMU Clinic and Polyclinic for Nuclear Medicine, explains the medical and healthcare policy aspects of this development, first pointing out that the organisation produces about a third of the substance for its own clinical purposes. These homemade tracers are extremely important, he adds, because they ‘enable us to perform very specific diagnostic procedures that are tailored to the relevant tumour.’

A twofold benefit

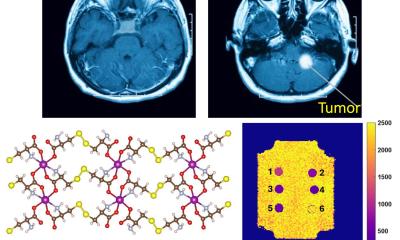

Neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) are diagnosed using a substance called DOTATATE, which attaches to somatostatin receptors – expressed by those tumours and thus identifying them. Even more: combined with radionuclides such as Lu-177 or Y-90 the radiopharmaceutical is introduced intravenously and travels through the entire body, allowing precise radiation – i.e. treatment – of the tumour. This is already clinical routine, the professor explains. In 85% of cases considered beyond therapy, this form of radiation may at least stabilise tumour growth. However, with an incidence of about 2.5 per 100,000 people, neuroendocrine tumours are rather rare.

Prostate carcinoma – first successes, but lots to be done

‘If we could transfer this principle of combining diagnosis and therapy to treat other, more frequent tumour types, prostate carcinoma, for example, that would be major medical progress that would benefit many, many patients,’ Prof. Bartenstein hopes. To diagnose prostate cancer, oncologists today use a substance developed in Heidelberg. This attaches to the prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA). If the radiopharmaceutical triggers a signal in the lymph nodes, metastases of a prostate carcinoma are confirmed because PSMA is over-expressed in prostate cancer. ‘As far as diagnosis is concerned, this is pretty good news; but we have to work on the corresponding therapy,’ he concedes. One of the major challenges is high radiation exposure of the kidneys – which needs further research.

Targeted therapy

The advantage of advanced radiopharmaceuticals is clear: Diagnosis is highly specific, a precondition for a targeted therapy tailored to an individual patient. With prostate cancer, for example, the diagnosis goes far beyond confirming enlarged lymph nodes: The antigen/radiopharmaceutical couple identifies the metastases of the prostate cancer cells. Based on the individual patient’s situation surgery is scheduled, or a personal radiation plan can be designed.

No widespread service

Pharmaceutical companies are known to focus their research on frequent – and thus profitable – indications, such as Alzheimer’s, to recover enormous costs incurred during the lengthy development and approval procedure for a new drug. However, neuroendocrine tumours are so rare that pharmaceutical firms shy away from any major investments. ‘We are closing this gap by developing substances to treat rare congenital diseases,’ Prof. Bartenstein explains. ‘It goes without saying that we do apply the same high level of safety standards as any pharmaceutical company.’

However, not every clinic though has the resources to operate a production lab for radiopharmaceuticals and, since the substances are cannot be marketed, there is a very real danger of a two-tiered healthcare system. ‘Patients who live far away from large research hospitals benefit less from such medical progress,’ the professor points out. Despite the much-discussed patient mobility, the reality cannot be denied: The further the geographical distance between a patient and state-of-the-art clinical services, the lower the likelihood that those services will be available for that patient. ‘This is a healthcare policy issue,’ Prof. Bartenstein says, ‘since it was a political decision to tighten pharmaceutical laws that helped to bring about this situation in the first place.’

Profile:

Professor Peter A Bartenstein has directed the Clinic and Polyclinic for Nuclear Medicine at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich since 2006. Following his medical studies and specialist training in nuclear medicine at Münster University, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) awarded him a research fellowship with the PET group at Hammersmith Hospital in London. From 1994-99, as senior resident at TU Munich, he led the institution’s entire in-vivo diagnostics and the Neurology working group at the PET Centre. He then headed the Nuclear Medicine Department at Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz before his return to Bavaria. He is Board Member of the German Society of Nuclear Medicine (DGN) and a member of the steering committee of the Biotech Cluster ‘m4’ of the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF).

03.03.2014