Know your enemy

High throughput sequencing technology enables analysis of protective intestinal flora that couldcombat Clostridium difficile

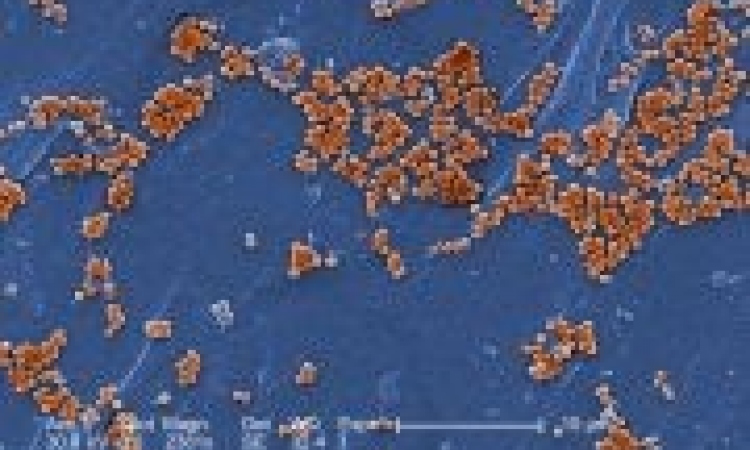

Along with MRSA and ESBL bacteria, Clostridium difficile is causing a growing problem. Epidemics of a new C. difficile strain have already occurred in hospitals in North America, England and the Benelux countries.

Although in its inactive state it is not harmful to humans, C. difficile can abruptly proliferate in the gut if the protective flora is disturbed due to antibiotic therapy; and then the toxins released by C. difficile can cause severe infections that can only be treated with special antibiotics. In some cases, this can lead to lasting damage to the gut flora, with subsequent recurrences of the infection.

One approach to prophylaxis and therapy would be treatment with the same intestinal bacteria that protect against C. difficile proliferations and release of toxins.

In Austria, a study is underway to identify the protective bacteria and consistency of intestinal flora, using high throughput sequencing technology. At the Graz Medical University, Meike Lerner of European Hospital asked Professor Christoph Högenauer MD, in the Clinical Department for Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University Clinic for Internal Medicine, why this identification has not been made before and what his expectations are for this year-long pilot study.

‘The normal gut flora is made up of around 104 bacteria and around 500 different types of bacteria in each individual,’ the professor explained. ‘With the technology available up till now, identification of the different types and their functions has only been possible in a very superficial way, because most types cannot be cultured or are only cultured with difficulty. This is why the role of the intestinal flora has so far been relatively unexplored. The Medical University Graz has recently installed the Genome Sequencer FLX System, which has high throughput as well as improved reading length and sequencing accuracy. We are now able to identify the intestinal bacteria via their DNA and map their consistency and functionality.’

Currently, patients are being evaluated and the researchers are examining the bacteria with the help of stool samples. ‘The samples are then sequenced and compared with a database. The objective is to find out which groups of bacteria in the gut have a protective effect against infection. If we achieve this we can then separate and culture just those bacteria and use them for therapeutic purposes. So far some patients with frequent, therapy-refractory relapses had to be treated with enemas that supplied the intestinal flora with the appropriate bacteria for the elimination of C. difficile. This is not particularly comfortable for patients. The development of new approaches to therapy and prophylaxis is becoming more pressing as C. difficile infections are an increasing problem for hospitals. The reason is the longevity of the spores, which often settle on the surfaces of bed frames, bedside tables and toilets and which cannot be eradicated with normal disinfection agents such as alcohol.

‘For the first time, this new technology offers us the prerequisites for mapping the intestinal flora,’ Prof. Högenauer pointed out. ‘Apart from C. difficile infection, we also expect to be able to put a name against some other “white spaces” on the map. The study is only the beginning of the research that we will carry out over the next few years.’

01.07.2008