Article • Emergency care

Keep it simple and straightforward

Emergency medicine requires smooth, patient-oriented and perfectly timed cooperation of several clinical disciplines.

Report: Sascha Keutel

‘Today, radiology is much more than a service provider. In emergency medicine we are an integrated and active component of the diagnostic process – and beyond’, says Professor Stefan Wirth, Managing Consultant at the Institute of Clinical Radiology, Ludwig Maximilian University Hospital, Munich.

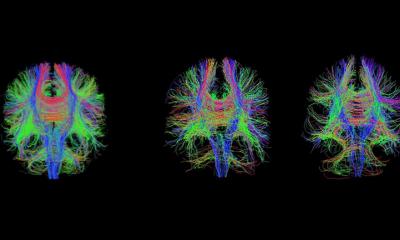

What would constitute a typical emergency case? The first thing most people think of is trauma, particularly polytrauma, explains Professor Stefan Wirth. ‘Depending on the situation, however, pulmonary embolism, acute abdomen, stroke, myocardial infarction and acute, meaning large internal or external haemorrhages, are typical cases. We have about 500 “real” polytrauma patients each year. Including the other serious and urgent emergency cases, we see more than 5,000 patients per year. If we add the less urgent emergency cases and those that need exclusion, such as cerebral haemorrhage, the number of patients increases to 25,000.’

A typical diagnostic check-up for trauma

‘Generally speaking, trauma patients are patients who suffered accidents of any kind, but not every trauma patient is an emergency case. Therefore, there are different routines. Ultrasound is very well suited to evaluate many musculoskeletal issues. While fractures are usually visualised in radiography, for some of them, such as spinal, elbow, pelvis or knee fractures, CT is not infrequently the better modality. Obviously each individual case requires a patient-oriented decision, taking into account issues such as radiation exposure.

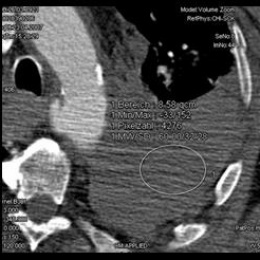

‘Actually, the diagnostic workup for polytrauma patients is pretty straightforward: The first step is the decision as to whether indeed we are dealing with a polytrauma patient, meaning a patient with acute and most likely life-threatening injuries. Simply sending the patient to the shock room won’t suffice. In a facility with the appropriate infrastructure – building and organisation – the severely injured patient immediately – meaning during patient handover undressing and initial stabilisation – undergoes a so-called eFAST. The aim of this extended focused assessment with ultrasound for trauma is to identify within 30 to 60 seconds intra-abdominal free fluid, haemoperitoneum or pleural effusion. An experienced physician will also be able to recognise pneumothorax during the eFAST. In all other cases immediate standardised whole-body CT is recommended.

‘In our hospital we use the shock room simply as transit room, so to speak, and take the patient straight to the CT table. Thus we save time and in an emergency, every minute counts.

‘I recommend positioning the patient feet forward into the CT gantry and folding the arms across the abdomen. This is easy to standardise, avoids cable clutter in the gantry, provides easy access to the head for any type of anaesthesia and spreads the artefact the upper extremities present across thorax and abdomen. Then we do a quick CT scout scan that shows all relevant pathologies as clearly as an X-ray scan, but is performed much faster. Moreover, the scout scan shows whether the standard protocol can be followed or whether a different route is preferable, for example in arterial and/or urography phase with pelvic injuries, or expanding the scan to the proximal femur if a serious femur fracture is involved.

‘Surprisingly, there is no guideline regarding the CT workup. Whilst only head, neck, thorax and abdomen scans are mandatory, there is evidence that whole-body CT increases patient survival rate. Therefore, I recommend unenhanced CCT, followed by neck/thorax/upper abdomen in arterial and the entire abdomen in portal venous phase.’

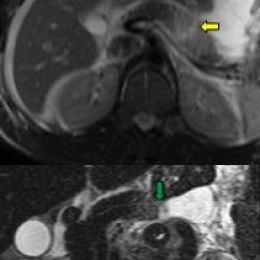

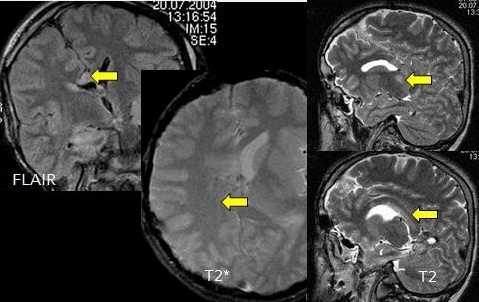

The need for emergency MRI

‘Emergency MRI is performed primarily to answer paediatric, neurological and musculoskeletal questions. Blunt trauma of the torso, except certain heart injuries, and acute neurological issues, don’t necessarily indicate an emergency MR scan. The following questions help to decide whether MRI is required:

- Can only MRI answer the question at hand, or are there other important reasons to prefer MRI, such as radiation exposure in children?

- If yes: is a treatment decision required that will be influenced by the result of the emergency MR scan, such as surgery versus no surgery?

- If yes: does at least one of the therapy options, based on the MRI results, need immediate action because, otherwise, the patient would suffer irreversible damage, such as re-fixation of joint cartilage?

‘If the answers to questions one through 3 suggest emergency MRI, limiting the sequences in number and respective time efforts might be discussed to arrive at a quick treatment decision.’

Emergency logistics, technology and staff limitations

‘You name them, we’ve got them; there are building issues, such as short routes, or whether the CT is located in the shock room. Which equipment is available – when and how many devices are available? What types of professional qualifications are available? In Germany, there is a severe shortage of radiology technical assistants because training takes a long time and is expensive and career opportunities are limited – as is the salary.

‘Many privately funded institutions offer attractive packages with regard to night shifts and salary, sometimes even a ‘poaching bonus’. Thus large public healthcare facilities in metropolitan areas have serious staffing problems. However, without the radiology assistant there is no radiology! That might sound overly dramatic, but indeed currently it is a huge issue.

A colleague said: ‘In emergency medicine radiologists are increasingly patient managers.’

The success of any emergency treatment depends on two things: standards and experience

Stefan Wirth

‘The success of any emergency treatment depends on two things: standards and experience. Emergencies such as polytrauma, or the sudden increase in patient numbers following massive accidents, are practised regularly. It sounds more complicated than it actually is, and can be achieved easily, as long as you keep the standards simple. If you only have one standard protocol it is quite trivial to spread knowledge and experience over the team. It is just a variant of ‘Keep it simple and straightforward’ (the KISS principle).

‘I’m talking above all about standards such as CT protocols. In general, quality management is also fully integrated in the workflows to ensure parameters, continuous improvement and instruments are part of quality control. We also look at interfaces, for example in the context of morbidity and mortality conferences.’

Profile:

Professor Stefan Wirth MBA EDIR, studied medicine and informatics at the Technical University Munich and Ludwig Maximilian University (LMU) Munich (1988- 98). He also holds an MBA from Munich Business School, a European Diploma in Radiology (EDIR) and is Managing Consultant at the Institute of Clinical Radiology at the LMU Hospital. He has also served as President Elect of the European Society of Emergency Radiology since 2015 to become President in 2017.

05.03.2016