Article • The difficulty? Unpredictability in the entire process

Immunotherapy for lung cancer patients

Better outcomes, more favourable prognoses – oncologists and their lung cancer patients didn’t dare to dream about it. Finally, there might be hope. The so-called checkpoint inhibitors (immunotherapy drug) have been used successfully, albeit not for every patient.

Report: Julia Geulen

They are a double-edged sword, with risks as well as opportunities, as explained by Professor Cornelia Schäfer-Prokop, a radiologist at the Meander Medical Centre Armersfort in the Netherlands.

Search and destroy

Certain proteins, called ‘checkpoints’, are located on the surface of T cells. These checkpoints can distinguish between tumour and body tissues. However, when blocked by tumour cells the immune system can no longer identify the tumour cells as foreign tissue and thus does not react. Checkpoint inhibitors are drugs designed to remove the blockage and make the immune system react.

Currently, several PD1- and PD-L1-inhibitors are approved to treat lung cancer. However, as Professor Schäfer-Prokop explains, ‘While this is a highly effective mechanism, the literature indicates that unfortunately it is successful only in 20 to 40 percent of all cases”.

Gene expression is an indicator of response

Before the use of a checkpoint inhibitor is considered, the tumour is characterised: a biopsy allows the classification of the histological subtype. Genetic characterisation identifies, inter alia. mutations such as EGFR or ALK, which promote tumour growth. Via gene expression the actual number of protein ligands in the tumour tissue can be determined. The more ligands, the higher the probability that checkpoint inhibitors will be successful.

Expression rates above 50 percent indicate a good response. ‘However, that makes things rather complicated; there are patients who respond well to immunotherapy despite low PDL expression,’ Schäfer-Prokop points out. Oncologists thus often feel obliged to at least attempt a therapy, even with low gene expression patients.

High expectations

For decades poor outcomes and poor prognoses have frustrated oncologists. Now, the checkpoint inhibitors might offer an effective therapy against lung cancer. Patients with a survival prognosis of just a few months now might hope to live 12, 15 or even 18 more months. ‘This explains the oncologists‘ enthusiasm,’ she says. The downside: the drugs are very expensive and have significant side effects. Since they intervene in the immune system in a rather untargeted way they might trigger severe inflammations in the organs, such as pancreatitis, hepatitis, pneumonitis or colitis, i.e. reactions that significantly impair patients’ quality of life. And last but not the least: not all patients benefit from the immunotherapy.

Prognosis is difficult

Molecular imaging, as well as the analysis of substances culled from the blood, the immune cells, or from immuno-histochemical features of the tumour itself – that’s conceivable

Cornelia Schäfer-Prokop

In view of these facts, prior to the therapy oncologist are eager to determine whether the patient will respond well or not. Thus researchers are frantically seeking biomarkers such as immuno-histochemical factors in the microenvironment of the tumour or the so-called mutational load, i.e. the number of mutations in the tumour. Schäfer-Prokop warns of premature optimism: ‘We are still in the research stage.’ The fact is, in the therapy response assessment imaging is called upon to move beyond mere morphology, since parameters such as tumour or lymph node diameter are insufficient because some tumours or nodes display pseudo- or hyper-aggressive behaviour.

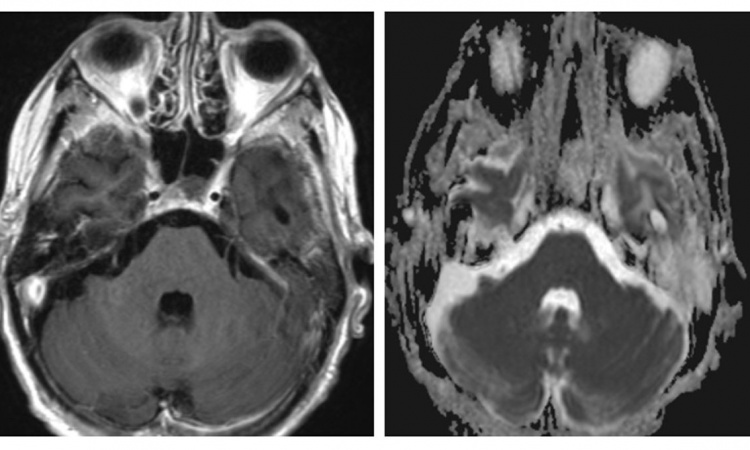

Molecular imaging with PET tracers may offer a solution, as do biomedical microsystems (BIOMICS) that can read image data. Schäfer-Prokop expects a combination of different sources of information to be most promising: ‘Molecular imaging, as well as the analysis of substances culled from the blood, the immune cells, or from immuno-histochemical features of the tumour itself – that’s conceivable.’

Image source: Wang et al. 2017; RadioGraphics

Immunotherapy does not immediately halt progression

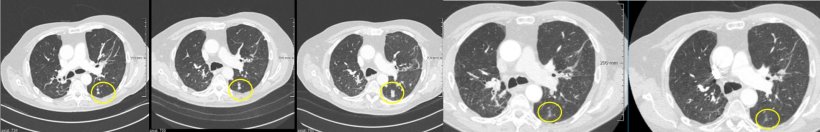

RECIST guidelines have been used since 2009 to classify response to lung cancer therapy with RECIST 1.1 applying to tumour response in conventional chemotherapy. The assessment is based on purely morphological features, i.e. the diameter of certain target lesions or lymph nodes and the development of new lesions. ‘If tumour volume has increased over a certain period of time, or a new lesion is detected, the verdict is “progression”,’ Schäfer-Prokop explains.

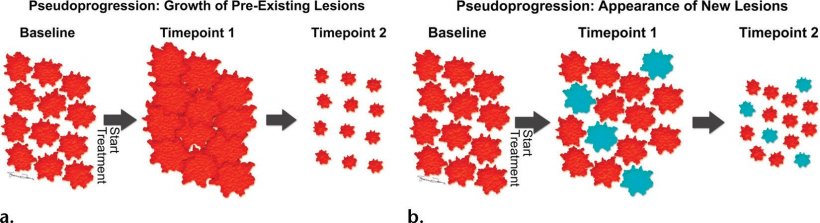

Today, however, we know that these criteria cannot be applied in the assessment of immunotherapies. In these therapies initial tumour growth was observed before the tumour, after several weeks, shrank significantly. Experts offer two possible explanations for this phenomenon: when the first assessment is performed, the immune system has begun to react, but not yet the tumour, thus the increased volume. Another explanation might be that activated T cells enter the tumour and the combination of tumour and immune reaction initially causes tumour growth. Only a follow-up assessment will show that the tumour has shrunk, or that the new lesions did not grow, or indeed did shrink.

RECIST was adapted twice

It is important that increased volume measured in the follow-up assessment is now considered the key criterion

Cornelia Schäfer-Prokop

These observations triggered the development of the so-called irRC criteria in 2009. They define ‘confirmed progression’ as a 20 percent tumour growth determined in two consecutive exams. In 2017, these criteria were further refined and are now called iRECIST. Currently, oncologists speak of an unconfirmed progression when the first assessment shows tumour growth and a new lesion. ‘Confirmed progression’ on the other hand means that a follow-up assessment shows that either the tumour or the new lesion has grown or another new lesion is detected. Schäfer-Prokop supports these new criteria: ‘It is important that increased volume measured in the follow-up assessment is now considered the key criterion.’

The unpredictability of the entire process – will the tumour continue to grow or will it shrink? – makes any decision as to continuation or suspension of therapy immensely difficult. In the end this decision will be informed by many factors: clinical status, the oncologist’s assessment of the likely outcome, the radiologist’s assessment of the imaging data, PD-L1 status and histological subtype.

Profile:

Professor Cornelia Schäfer-Prokop joined the Meander Medical Centre, Amersfoort (Netherlands), in 2009. The radiologist also researches at the Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine at Radboud University Medical Centre in Njimegen. From 1993 to 1998 she was in Hanover, from 1998 to 2004 at AKH Wien and from 2005 to 2009 at AMC Amsterdam. Her research focus is digital radiography, computer-aided detection and classification, as well as diagnostics of interstitial lung disease. She has been a member of the Editorial Board of European Radiology, the Journal of Thoracic Imaging, Radiology and Insights into Imaging; she is also member of the Fleischner Society.

16.07.2020