Article • Cancer pseudoprogression

Immunotherapy: Bigger lesions, better outcomes

With immunotherapy, bigger lesions may be spotted on CT, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that the disease is progressing.

Report: Mélisande Rouger

As treatment works, it can cause what has become known as pseudo disease progression; and this is just one of the many revolutions immunotherapy is triggering in oncology imaging, Professor Clarisse Dromain (Lausanne/CH) explained as she opened the session dedicated to this game changing treatment, Friday morning at ECR. In the last few years a whole range of immunotherapy approaches have been developed including non-specific immune-stimulant, adoptive T-cell therapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors (anti CTLA-4, anti PD1 and anti PDL1). The most commonly used and intensively studied are the immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), which have a profound impact on cancer treatment, Dromain explained.

If you stop immunotherapy you have a very long duration of response without progression. This is really specific to immunotherapy

Clarisse Dromain

“Their mechanism of action signifies a true shift in oncology. Instead of targeting tumor cells, ICIs target the immune system to break cancer tolerance and stimulate anti-tumor immune response,” she said.

These new drugs have been available on the market since 2011, for melanoma, lung, bladder, renal, and head and neck cancer, with remarkable and long-lasting treatment response. Because they trigger immune and T-cell activation, ICIs lead to unusual patterns of response. “First and foremost, we observe delayed response. We have a lot of stable disease with very slow, steady decline in total tumor volume and this is really a long duration response,” she said. It is interesting to look at durability of response in patients who discontinued due to toxicity, Dromain added. “If you stop immunotherapy you have a very long duration of response without progression. This is really specific to immunotherapy.”

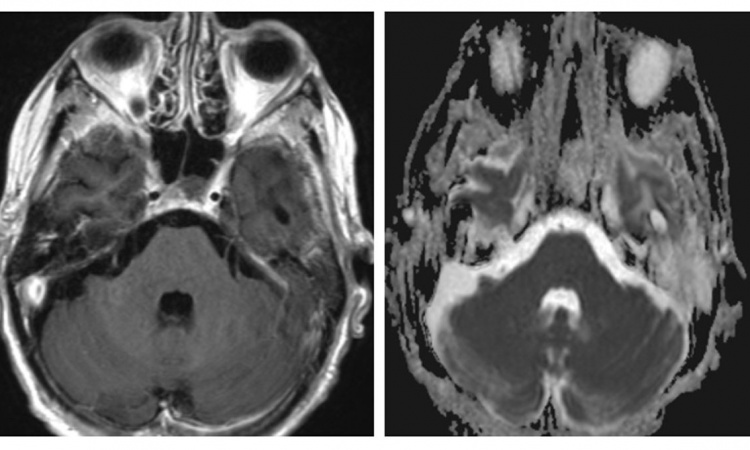

New types of response have been spotted on imaging, such as flare phenomenon and response after initial increase in tumor border and initial appearance of new lesions. “These new types of response are called pseudo-progression, and could be due either to infiltration of the tumor site by immune cells or continued tumor growth until a sufficient response develops due to the time required to mount an adaptive immune response,” Dromain explained.

Recent research suggests that pseudo progression with anti PD-L1 may appear in about 5% of patients. An increase of tumor burden during immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) treatment is more likely to reflect true progression than pseudo-progression, Dromain said. “It’s an important point because we talk a lot about pseudo-progression, but true progression is more common.” The immune system may be more reactive in a younger population and pseudo progression could be associated with a clinical worsening, especially in lung cancer. Pseudo progression may occur at any time, but has mostly been observed around 12 weeks after the onset of therapy, especially in melanoma. Last but not least, pseudo progression may concern all organs, but most commonly lymph nodes, lung and liver.

Dromain shared the case of a patient with colic cancer MSI positive, “a very nice indication for immunotherapy”, who showed progression after 3 types of chemotherapy. “We did a clinical trial and tested an anti PD-L1 for liver metastasis. A few months after treatment onset, we saw very good response in the liver of this peritoneal lymph node. We suggested the possibility of flare phenomenon and performed cytology by aspiration of lymph node. This showed mature lymphocyte, so we continued the treatment and the response was very good in the liver. The lymph node disappeared,” she said.

New criteria have been developed to be able to manage this new type of response. To overcome the limitation of RECIST criteria to assess these specific changes in tumor burden, so-called irRC criteria were established, on the basis of WHO criteria (bi dimensional measurements, end target lesion + 5 cutaneous target). “This was really designed for melanoma. The main difference compared to classical WHO criteria is the inclusion of the measurements of new target lesions into disease assessments and the need of a 4-week CT re-assessment to confirm progression,” she explained. Things did not turn out so well in clinical practice. “It was a real nightmare to have 15 target lesions, this 2 dimensional measurements. So we established iRECIST, which are based on one-dimensional measurements and include the same choice of lesions,” she said. And last year, the RECIST working group developed a new consensus guideline, iRECIST, which recommends assessing lesions (target, non target and new) separately.

Pseudo-progression should be considered until PD is confirmed, but there is a lack of scientific rational regarding time window to do so, Dromain explained. “Studies give different results. For example Nishino et al observed 103 patients with melanoma, with 4% of pseudo-progression. Median time to peak tumor burden was 5.5 months, median time to the first scan showing tumor burden decrease compared with the prior scan was 6.8 months, and all patients had 2 or more consecutive scans demonstrating PD over the time frame of 4 weeks before response. But recently the RANO working group on neuro-oncology recommended a 3-month period for confirmation of PD.”

Profile:

Clarisse Dromain MD PhD, head of the cancer imaging department at Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus University Hospital, Paris, researches interventional and diagnostic breast imaging. She is a member of the European Society of Radiology and several other international and national scientific organisations.

Session: C. Dromain: CT: looks bigger, but it's better, ECR 2018

02.03.2018