Genom

I looked into my genes and changed some habits

“These dates we have access to a lot of genetic information which had previously not been available to us. For the individual, this can provide options for action with regards to leading a healthier lifestyle or to try and prevent diseases,” knows Dr. Theodor Dingermann. The senior professor of the Goethe University in Frankfurt am Main has had his own genome decoded. In parts, the result changed his life.

Interview: Sascha Keutel

Professor Dingermann, why did you have your genome decoded?

I am a molecular biologist and a curious human being when it comes to this topic. I also have a weakness for wanting to find out and document things about myself, and this includes genetic information. Apart from my personal curiosity I also wanted to gain experience of new sources of information using a concrete example – and using myself as a test object lent itself to this purpose.

How is this analysis carried out?

There are several options but they all have the same approach. I have also had several analyses carried out, the first of which by a company called 23andme.com. I was sent a test kit with a small test tube which I filled with saliva and returned. I received the result a few weeks later in the shape of a homepage with a lot of information. At 1.2 million data points the information is so comprehensive - but at the same time not commented on enough by experts - that around two years ago the FDA temporarily thwarted the company’s activities. Meanwhile however there has been an agreement on the amount and quality of information provided.

I provided consulting services to Humatrix, a company which offers a different type of genetic test. One of these tests – Stratipharm – makes statements on how the body deals, or is respectively likely to deal, with certain medication. The statements are independent of whether or not the person being analysed is taking the medication when the analysis is carried out. DNA is isolated from a mucosal swab and then 31 genes, the genetic products of which all have an impact on the effectiveness and tolerability of drugs, are tested for mutations. These can, for instance, be enzymes involved in metabolism, or transporters which are utilised by active agents to enter or respectively exit the body. These proteins interact with drugs independent of the diseases for which the drugs are licensed as treatment. This makes it possible to correlate the mutation pattern of these 31 genes with the entire range of drugs licensed in Germany and to use the result to analyse which drugs could lead to problems if they are taken. In my case it turned out that there were about 40 active agents which were unlikely to be effective if taken.

What other findings where there and what conclusions did you draw from these for yourself?

The analysis carried out by 23andme showed that I had a 100% increased risk of developing Type 2 Diabetes. This may still be quite a small risk, no bigger than it would be if I was overweight, but these are risks which should be taken seriously these days. I took it seriously indeed, especially as there were also other indicators which hinted at the fact that I may well be confronted with a Type 2 diabetes diagnosis at some stage. I watch my diet a lot more and do a lot more sport.

Another example: My test showed that I have a considerably increased risk of developing age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Although the ophthalmologist did not diagnose AMD when I had this checked he actually found a glaucoma which required urgent treatment. In other words: I have drawn conclusions from the genetic test which are important to me and which have also proved beneficial for me.

So these were all positive effects. Should everyone have their genes analysed?

No, I don’t think so. To the contrary, a test like this should not be taken lightly. One has to be careful how one evaluates this type of data for oneself. Mostly we only focus on the problems indicated by these tests, i.e. the increased risk of developing disease x or y. However, such genome analyses don’t only show the risks. They also indicate parameters which demonstrate that an individual may be in a better position compared to the general public, i.e. has a lower risk of developing certain diseases. The greatest weakness of such analysis is that only probabilities are revealed which a layperson will find difficult to assess. If you have even the slightest doubts as to how you will be able to cope with the results you should not have a test like this carried out under any circumstances.

So gene analysis will not become a standard test?

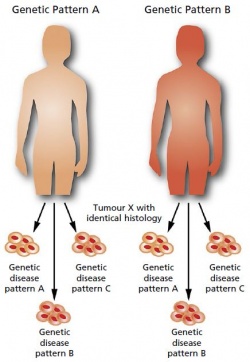

I wouldn’t put it like that. Currently, most genetic analyses are carried out when they are indicated in the context of cancer treatment. The tumour genome, which is different to the so-called germline genome found in all healthy cells, is examined for the purpose.

I imagine that analyses carried out to determine the effectiveness and tolerability of medication could actually become a type of standard. It does actually analyse the germline genome. And the results are much clearer than those achieved in the analysis of health risks. Drug-related analyses can predict with great certainty whether an individual actually comes within the Gaussian distribution curve which is applied to assess responders for drugs, or whether they are likely to be amongst the non-responders for certain drugs. The same applies to the prediction of intolerability reactions.

An example: If the analysis shows that a statin cannot be metabolised correctly then this will also show when the statin is actually administered. Or it may come to light that an individual is unlikely to be able to break down a cytostatic drug in the same way as the general population because of their specific genetic make-up. This is an extremely important finding as this patient must be given a significantly lower dose of the cytostatic agent to achieve the same effect, and respectively to prevent the occurrence of severe toxic problems which could arise with the administration of a “normal” dose.

PROFIL:

Theodor Dingermann studied pharmacy at the Institute for Applied Chemistry at Erlangen University. The licensed pharmacist wrote his doctorate in February 1980 on “Regulator Functions of Specific Transfer Ribonucleic Acids in the Development Cycle of the Cellular Slime Mould Dictyostelium discoideum.” In January 1987 he wrote his habilitation treatise on “Transcription Mechanisms of Eukaryotic Tranfer RNA Genes.” The professor for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology taught at the Institute for Pharmaceutical Biology at the Goethe University in Frankfurt am Main. He has been a Senior Professor there since October 2013.

11.11.2015