Article • Study

Hepatitis control must be accelerated

Last year the WHO launched a global strategy on viral hepatitis aiming to eliminate hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV) as public health threats by 2030.

Report: Sylvia Schulz

Among the goals: a 90% drop in the number of chronically infected people and a 65% mortality rate reduction, as untreated chronic viral hepatitis can cause irreversible liver damage leading to cirrhosis or Cancer.

The global health organisation, clearly demonstrating that hepatitis is not only a problem among third world countries but is also a current European issue, set up an action plan last September. Europe records around 57,000 newly diagnosed acute and chronic cases of hepatitis B and C annually. On top of that, an estimated 10 million Europeans are believed to have chronic hepatitis B and C infections without knowing it or being treated.

As the monitoring and evaluation framework of the WHO hepatitis strategy is not expected to become operational until 2018, the European Liver Patients Organisation (ELPA) surges ahead, compiling facts about state of the art care concerning this disease. It commissioned a broadly based, the Hep-CORE study, to shed light on the policy response to hepatitis B and C engaging with ELPA member organisations.

Based at the University of Barcelona and Copenhagen, the research team carried out the survey, with data collected from local specialists in each country. The researchers asked one patient group in each of ELPA’s 27 member-countries to complete a 39-item survey about various aspects relating to HBV and HCV: overall national response, public awareness and engagement, disease monitoring and data collection, prevention, testing and diagnosis, clinical assessment, and treatment. The plan is to repeat the patient-led monitoring tool on a regular basis, to compare results between countries and follow individual country progress over time.

In brief, the study reveals serious gaps in policies concerning hepatitis control. 52 per cent of the 27 European countries surveyed lack national strategies to address viral hepatitis B or C despite the WHO’s Assembly resolution calling on all countries to have one. Only three of those countries have access to the new, highly effective medicines (direct-acting antivirals) for hepatitis C without restrictions. The director of studies, Professor Jeffrey V Lazarus, from the University of Barcelona, said: ‘These Hep-CORE results serve as an unprecedented analysis of regional and national gaps, clearly showing where there are deficient policies and, by default, what action needs to be taken.’

No national register

Viral hepatitis must be combated on a large scale

Professor Jeffrey V Lazarus

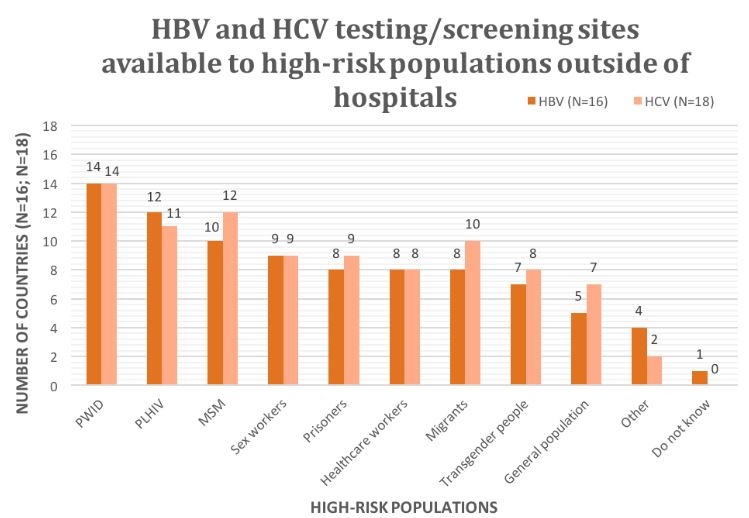

For example, despite an urgent need for broad monitoring and disease surveillance, this study found that 17 countries (63%) have no national hepatitis B virus (HBV) register and 15 countries (56%) have no national hepatitis C virus (HCV) register. Basic access to testing and screening facilities is vital for patients, especially those from high-risk groups, such as people who inject drugs, or prisoners.

Despite this, patient groups from 10 countries (37%) reported that there are no HCV testing or screening sites outside of hospitals for the general population in their countries. Even more alarming, patient groups from 12 of the countries (44%) reported that there are no such sites outside of hospitals that provide testing or screening services for high-risk populations.

Another section of the survey asked a set of questions oriented towards understanding hepatitis prevention in each country. This section focused on the availability of harm reduction – services that target the reduction of negative health consequences associated with drug use, such as the spread of viral hepatitis.

It was reported that clean needle and syringe programmes are available in at least one area of a patient group’s country in 22 cases (81%), that opioid substitution therapy is available in at least one area of a patient group’s country in 24 cases (89%), and that drug consumption rooms are available in only five cases (19%). The study shows that significant gaps in harm reduction regarding reported coverage and availability remain.

Lazarus concludes: ‘The 2016 Hep-CORE Report findings are a resource that can aid the efforts of all those working to eliminate HBV and HCV as public health threats in Europe, and beyond, in line with WHO’s global strategy. We now have a starting point from which we can systematically scale up hepatitis prevention, treatment, and care – and monitor the much-needed progress. Viral hepatitis must be combated on a large scale and this requires individual country and concerted pan-European action.’

20.04.2017