Article • Pros & cons

Goodbye to the microscope? Not yet!

Carol - I. Geppert MD, from the Institute for Pathology at Erlangen University Hospital, Friedrich Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg, debates the impact of digitisation on pathology.

Digital Pathology (DP) is the fastest growing area of pathology, along with molecular pathology. However, the use of digital tools such as scanners and analysis software, as mentioned in a previous article, is mainly limited to academia (volume 24. issue 6/15). Academic medicine benefits most in teaching and research where larger investments can be applied for without the pressure of daily clinical routine, or the economic pressures of the health system.

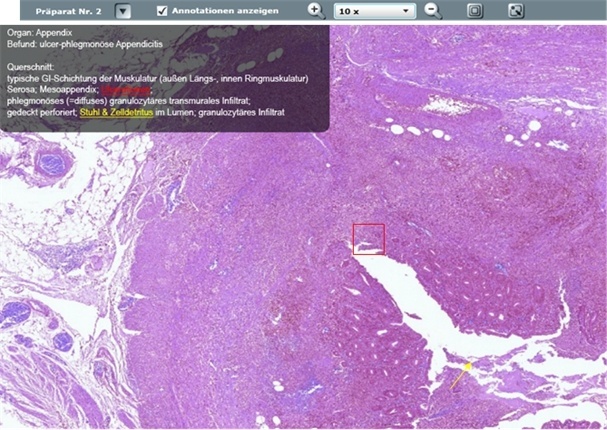

In Erlangen, DP has been an established part of teaching in human, molecular, and dental medicine. Using an online-microscope, students from Würzburg, Regensburg and Erlangen (Cooperation partners: the universities and university hospitals as well as the Fraunhofer Institute Erlangen) can access digital slides from their respective courses browser-based via the internet, from anywhere and can study with superimposed texts and annotations (image 2). In addition, in recent research some projects have also been driven with the help of DP within the Comprehensive Cancer Centre Erlangen–Nuremberg, addressing problems from different clinical fields. DP already plays an important part in national and international cooperation projects.

Naturally, new and fast-paced technology also has its limitations, which need to be clearly stated. The error rate of the scanners with slides or low contrast, or errors in digital image analysis (DIA) caused by artefacts can negatively impact on trust in this new technology. Therefore, there is also some criticism and scepticism amongst pathologists.

I believe many pathologists are following the rapid developments in digital pathology with excitement and interest, as well as with scepticism.

Carol - I. Geppert MD

Furthermore, next to the many advantages of DP there are also clear disadvantages, such as high initial investment costs for scanners and data storage, as well as the on-going costs for maintenance and support. Pathology will be confronted with similar problems to those seen in radiology years ago, during the initial conversion to digital image processing. Although terabyte (TB) mass storage is now comparatively affordable, the amount of data involved in DP is extremely high. One case with five sections can take up between 2.5 to 20 gigabytes (GB), i.e. the equivalent of a vast storage requirement of several 1,000 TB, which converts to several PB per year, assuming all cases from one large centre were to be digitally stored every year. This new dimension of data exceeds the requirements in radiology by tenfold and would therefore be unprecedented in clinical medicine.

By contrast, there is the new dimension of the interpretability of an immeasurable number of cells with their colourings for immunohistochemistry, CISH or FISH. New analysis software – digital image analysis (DIA) – from companies such as Definiens or Indicalab, can quantitatively evaluate all cells from one section. This can be a routine section for one patient or samples from many patients via tissue micro arrays (TMAs), where more than 400 samples can be put on one slide (such as GrandMaster, 3-D-histech, Hungary). This will deliver completely new and detailed views of tumours and their specific biomarkers. Although previously we could gain good and realistic estimates with the bare eye, we can now generate far more exact evaluations of hundreds of thousands of tumour cells in one section, for instance for each individual tumour cell. Until recently this was completely impossible.

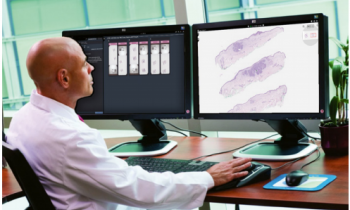

The integration of individual parts of DP into clinical routine is already happening in interdisciplinary tumour boards and conferences, in telepathology and through the transmission of digital slides in the context of studies or consultations. It has facilitated a much faster, worldwide exchange between experts and colleagues without the need to physically send sections. As there has been an abundance of new technologies and innovations over the last few years and a continuously expanding market for imaging equipment (scanners and the camera technology used in them) for image processing (reconstruction and visualisation software) as well as for digital image analysis (DIA) the need for standards for diagnosis and research has become equally imperative.

If, one day, DP was to become established in daily routine it will have to withstand comparison with the microscope in daily practice, in terms of practicability, sturdiness and, most importantly, speed. The microscope is unlikely to disappear. Some areas, such as quick section diagnosis where a diagnosis has to be achieved within 15 minutes during on-going surgery, there can be no digitisation. However, we (including Professor Peter Hufnagel at the Charité Berlin and Professor Gian Kayser at Freiburg University Medical Centre) believe that, more and more pathologists will mainly work digitally, and also beyond university settings, in the distant future, because the requirements from this field will continue to grow and the investment costs for scanners and data storage are likely to fall due to increased competition. In our view the full potential of DP, which is as versatile as it is promising, has not yet been exhausted, by far. However, high quality standards in image generation, processing and analysis must be established independent of manufacturers. They should be the basis for the continuously growing and ambitious community of pathologists in diagnostics, research and teaching. DP can help achieve a new measure of quality, particularly in the growing field of cancer diagnostics (companion diagnostics) with immunohistochemical biomarkers such as Her2 or PD1/PD-L1, which are decisive for treatment.

The tool will become a robust, reproducible, secure, comprehensively quantitative and observer-independent aid for diagnosis. With the help of DIA, important biomarkers, such as prognosis parameters, can be completely, quantitatively, digitally evaluated (e.g. Her2-FISH in Z-stack) even three-dimensionally. DIA is therefore superior to the previous methods, as it makes millions of tumour cells analysable, if necessary even in several layers (for FISH signals).

Furthermore, observer-independent, digital evaluations will lead to a location-independent, comprehensive increase in diagnostic quality for certain problems, be it in a large centre or a peripheral practice.

Along with many well-known pathologists we believe that DP will have become an established part of a hybrid workflow consisting of DP and conventional microscopy in clinical routine within the next 10 years. The advantages speak for themselves and there is no end in sight for the rapid developments and resulting opportunities for application.

I believe many pathologists are following the rapid developments in digital pathology with excitement and interest, as well as with scepticism. Most of them are not yet happy to swap their microscopes for computers. However, within the next ten years I believe that a hybrid diagnostics workflow, consisting of conventional microscopy and digital image analysis, will be established. A comprehensive change to purely digital diagnostics is still a long time coming.

23.05.2016