German breast screening

Success: A higher detection rate of smaller tumours and carcinoma without lymph node involvement at follow-up

Germany’s mammography screening programme, introduced in 2005, was rolled out across the country in 2009 for women between the ages of 50 and 69 years. The mammo screening coordination office, which heads up and monitors the country’s 94 screening units, has published for the first time an evaluation report with follow-up examinations after a twoyear period.

‘We are well on our way to lowering the breast cancer mortality rate and hope that we’ll be able to present figures by 2018 similar to those in the Netherlands, where the mortality rate for women dying from breast cancer has dropped by up to 35% thanks to screening,’ explained Dr Karin Bock, head of the mammography southwest reference centre in Marburg.

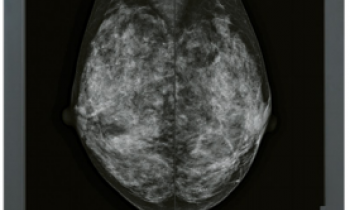

Reliable information on the effects of screening on mortality can only be made around 9-12 years from the start of the screening programme; in Germany this would not be possible until 2015. However, even seven years after the introduction of screening in the first German States, success is clearly visible: 30% of all invasive carcinomas detected at the first screening examination are smaller than 10mm in size. At follow-up after two years this figure even increases to 35%. By comparison, before the introduction of screening this figure was only 14%. ‘The best chances for successful treatment are those for women with small tumours that have not spread. The affected women also benefit from a gentler and mostly breast-preserving therapy,’ Dr Bock pointed out.

Larger tumours (more than 2 cm), which are less favourable from a prognostic point of view, make up only 23% of all invasive carcinoma detected at the first screening and 19% at the follow-up screening, whilst this figure was 40% before the introduction of screening. 80% of tumours detected are invasive, i.e. metastasising carcinoma. At the point of the first screening there was no lymph node involvement in 75% of women, and at the second screening this percentage even increased to 79%.

However, the screening coordination office is concerned that only around 50% of those invited for screening take up the option. Dr Bock sees the best advertisement for screening is those good results: ‘There are fewer deaths, fewer amputations and less invasive treatment.’ She does not believe that a legal obligation is the way forward, but that the correct and comprehensive education of women as the basis for voluntary participation in screening is very important. The involvement of GPs and gynaecologists in screening conferences is a further measure to increase the acceptance of screening. Due to the women’s increased life expectancy the gynaecologist also advocates the extension of the examination age to 75 years. ‘I consider the statistical rationale that women over the age of 70 are more likely to die from a diagnosis other than breast cancer to be problematic. The current limitation of screening only up to the age of 69 goes back to a time where the average life expectancy of women was 75 – that figure has now increased to 85 years.’

10.07.2012