From Dusseldorf around the world

The cardiotograph — Born 40 years ago in Dusseldorf

Today — A vital tool for births around the globe

This was not a quick birth. The concept began back in 1963. After finishing each day's work at the Women's Hospital, Dusseldorf, obstetrician Konrad Hammacher spent his nights at the Medical Academy, toiling over an idea.

His aim was to develop a machine that would continuously monitor the foetal heartbeat and correlate this it with the mother’s contractions.

The result was a new invention, the cardiotograph (CTG) – a piece of equipment set to revolutionise birth monitoring. The particular feature of Dr Hammacher’s idea was the ‘beat-to-beat’ measuring of cardiac sounds. This method captures the foetal heart sounds not as an average cardiac frequency but as the respective, current interval between two heart sounds, which continuously changes. This type of electronic fatal measuring established itself and is still used, because the heart rate variability brings obstetricians important conclusions about a baby’s health.

One year later, Dr Hammacher was ready to hand over his prototype to what was then still Hewlett Packard, so that the company could bring his invention to the marketplace. However, it took four more years of work before the HP8020 was finally launched.

‘Based on individual observations, we were very aware that many babies would not have been delivered healthy without this equipment,’ says Otto Gentner, who had been involved in the development of the cardiotograph at HP. Professor Sabaratnam Arulkumaran, lecturer and Head of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at St George’s Hospital London, is also convinced that there is no better way to monitor the unborn than by using cardiotography: ‘The CTG delivers such reliable data that the doctor can often detect possible diseases or birth problems at such an early stage that he can prevent them in time.’

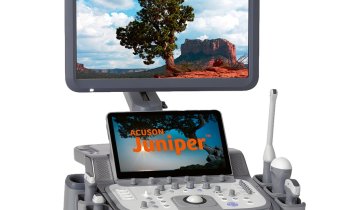

Today’s cardiotograph helps midwives and obstetricians to monitor pregnancies and births all over the world. ‘The requirements and problems vary significantly, depending on the state of development in individual countries,’ says Michael Spaeth, head of international marketing in the Philips Healthcare perinatal division. ‘In developing countries the main concern is to offer basic care, in developed countries the increasing number of multiple births, for instance, requires new and better monitoring systems.’

Before Dr Hammacher’s invention, the wooden Pinard stethoscope had been used during deliveries since 1871. Midwives, obstetricians and doctors pressed this against the pregnant woman’s abdomen to listen to fatal heartbeats. The weakness of that device was that it only captured a fraction of the heartbeats because, due to time restraints, midwives and obstetricians could not use the stethoscopic continuously. Obstetrician Hammacher knew only too well, from daily practice, that the patchy information gained was insufficient.

As with all medical technology, that first invention has continued to evolve, giving birth to generations of upgraded machines. ‘Since his prototype we have further developed each of the following generations of equipment with the respective technology available to us at the time,’ says Martin Maier, international product manager for fatal monitoring at Philips. ‘We have improved sensitivity and performance continuously and have made a significant leap forward, particularly regarding women’s level of comfort.’

For the last five years, Philips in Böbligen, Germany, has been producing cordless cardiotographs. ‘Births are experienced differently these days,’ Michael Spaeth points out. ‘Both parents want to be there and there is an increased requirement for privacy – technology must not be too prevalent.’ Giving birth is an experience which the parents — particularly the mother — want to feel comfortable about.

21.11.2008