Clostridium difficile

Evidence supports success of fecal transplants in treatment

Research published in the open access journal Microbiome offers new evidence for the success of fecal microbial transplantation (FMT) in treating severe Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), a growing problem worldwide that leads to thousands of fatalities every year.

Research led by Michael Sadowsky, Alex Khoruts, and colleagues at the University of Minnesota in collaboration with the Rob Knight Lab at the University of Colorado, Boulder, reveals that healthy changes to a patient's microbiome are sustained for up to 21 weeks after transplant, and has implications for the regulation of the treatment. Findings also demonstrate the dynamic nature of fecal microbiota in FMT donors and recipients.

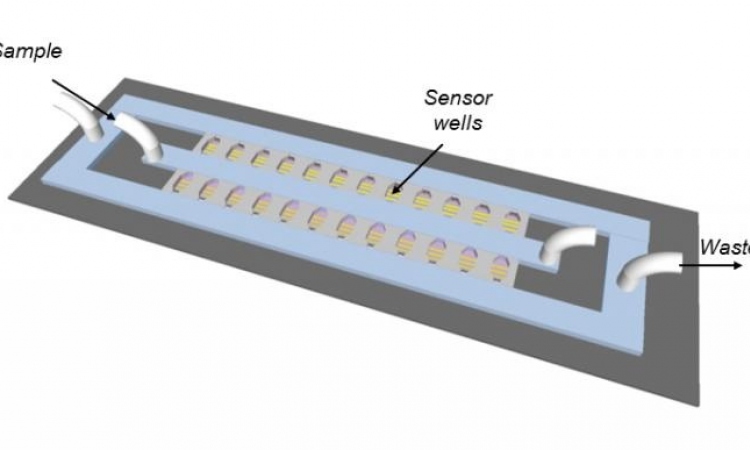

In FMT, fecal matter is collected from a donor, purified, mixed with a saline solution and placed in a patient, usually by colonoscopy. In contrast to standard antibiotic therapies, which further disrupt intestinal microflora and may contribute to the recurrence of CDI, FMT restores the intestinal microbiome and healthy gut function.

Using DNA samples of healthy individuals from the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) as a baseline, Sadowsky and his team compared changes in fecal microbial communities of recipients over time to the changes observed within samples from the donor. Significantly, the composition of gut microbes in the both donor and recipient groups varied over the course of the study, but remained within the normal range when compared to hundreds of samples collected by the HMP.

According to Sadowsky, the findings have important implications for a range of diseases associated with microbial imbalance, or dysbiosis, and could influence the regulatory regime surrounding FMT, currently treated as a drug by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (USFDA).

"The dynamic nature of fecal microbiota in both the donor and recipients suggests that the current framework of regulation, requiring consistent composition, may need to be reexamined for fecal transplantations," says Michael Sadowsky. "Change in fecal microbial composition is consistent with normal responsiveness to shifts in the diet and other environment factors. Variability should be taken into account when comparing microbial composition in normal individuals to those with dysbiosis characteristic of disease states, especially when assessing clinical interventions and outcomes.

Also discovered in the research, the performance of frozen and fresh preparations of fecal material was indistinguishable. Though the sample was limited and warrants further study with a larger cohort, it has several implications for the widespread adoption of FMT. The frozen preparation greatly simplifies the standardization and distribution of the fecal material. It also facilitates long-term storage of donor material for future study and makes FMT accessible to a greater number of physicians and patients. Finally, it offers advantages over fresh material in the testing of fecal samples for pathogens, which in some cases can take several weeks to complete.

While FMT is particularly successful in patients who suffer from recurrent CDI, University of Minnesota researchers led by Sadowsky and Dr. Alex Khoruts are currently preparing for a clinical trial using FMT to improve insulin sensitivity in pre-diabetic patients and to treat metabolic syndrome.

Source: University of Minnesota

13.04.2015