News • Cancer research

Esophageal cancer “cell of origin” identified

Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) researchers have identified cells in the upper digestive tract that can give rise to Barrett’s esophagus, a precursor to esophageal cancer. The discovery of this “cell of origin” promises to accelerate the development of more precise screening tools and therapies for Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma, the fastest growing form of cancer in the United States. The findings, made in mice and in human tissue, were published in the online edition of Nature.

In Barrett’s esophagus, some of the tissue in the tube connecting the mouth to the stomach is replaced by intestinal-like tissue, causing heartburn and difficulty swallowing. Most cases of Barrett’s stem from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)—chronic regurgitation of acid from the stomach into the lower esophagus. A small percentage of people with Barrett’s esophagus develop esophageal adenocarcinoma, the most common form of esophageal cancer. Incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma has risen by 800 percent over the past four decades. However, little progress has been made in screening and treatment over the same period. If esophageal cancer is not detected early, patients typically survive less than a year after diagnosis.

Study on mice

Researchers have proposed at least five models of Barrett’s esophagus, each based on a different cell type. “However, none of these experimental models mimics all of the characteristics of the condition,” said study leader Jianwen Que, MD, PhD, associate professor of medicine at Columbia. “This led us to believe that there must be another, yet-to-be-discovered, cell of origin for Barrett’s esophagus.”

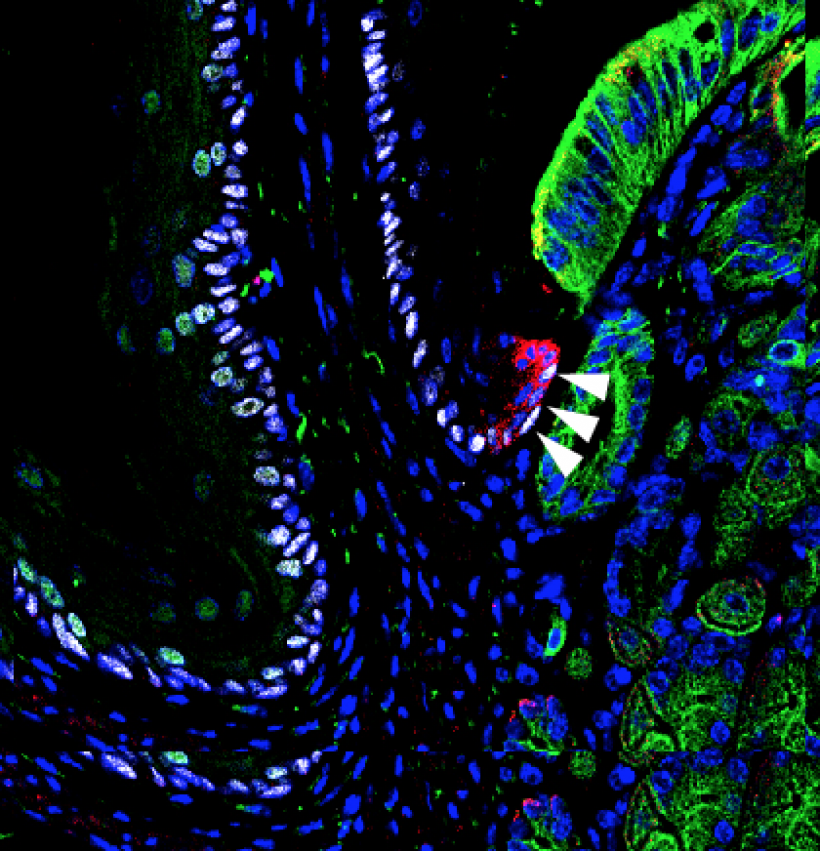

In the current study, Dr. Que and his colleague, Ming Jiang, PhD, an associate research scientist in CUMC’s Department of Medicine and first author of the paper, genetically altered mice to promote the development of Barrett’s esophagus. His team then examined the mice’s gastroesophageal junction tissue for changes. “All of the known cells in this tissue remained the same, but we found a previously unidentified zone populated by unique basal progenitor cells,” he said. Progenitor cells are early descendants of stem cells that can differentiate into one or more specific cell types.

Lineage tracing

Now that we know the cell of origin for Barrett’s esophagus, the next step is to develop therapies that target these cells or the signaling pathways that are activated by acid reflux.

Dr. Que

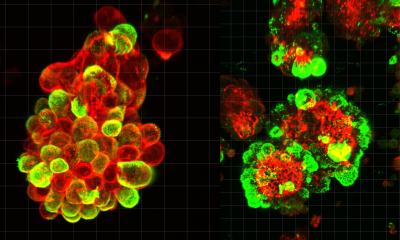

Dr. Que’s team then performed a technique called lineage tracing to determine if these unique basal progenitor cells, tagged with a fluorescent protein, can give rise to Barrett’s esophagus. In the tests, several mouse models were used to show that bile acid reflux or genetic changes promote expansion of these cells, leading to the development of Barrett’s esophagus. The same observations were made in organoids (artificially grown masses of cells that resemble an organ) created from unique basal progenitor cells that were isolated from the gastroesophageal junction in mice and humans. “Now that we know the cell of origin for Barrett’s esophagus, the next step is to develop therapies that target these cells or the signaling pathways that are activated by acid reflux,” said Dr. Que.

Source: Columbia University Medical Center

18.10.2017