Dysglycaemia

Greater glucose control in the ICU is critical for every patient Dysglycaemia

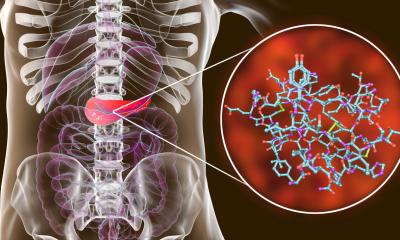

Dysglycaemia is a new term in critical care that recognises the vital importance for glucose monitoring of patients in the intensive care unit (ICU). Beyond the clinical consensus over this word for grouping critically ill patients with hyperglycaemia, hypoglycaemia or high blood sugar, there is no broad agreement on how best to manage these patients. Report: John Brosky.

In-patient glucose control was a central discussion at the 2011 International Hospital Diabetes Meeting in Barcelona this November. There is little controversy in the clash of clinical opinion. Instead, debate centres on how conservative or aggressively patients should be treated to maintain acceptable glucose levels and the quality of evidence for determining the right approach. Even when clinicians encounter diabetes in the ICU, a condition that clearly indicates a need for careful attention, there is not agreement on how to best manage these vulnerable patients, according to Ingrid Mühlhauser MD, from the University of Hamburg in Germany,

who presented ‘The Future of Guidelines for In-Hospital Care’ and then moderated a session dedicated to clinical management of diabetes in the hospital.

Most hospitals have some kind of guidance for the management of diabetes, she told European Hospital, but the effectiveness and efficiency of guidelines are poorly evaluated. The number of guidelines continues to grow with ‘a huge number of statements and recommendations dealing with diabetes care,’ she said. Yet the overall quality of guidelines is low as they are often not evidence-based, the conclusions on identical topics are often at variance, and even where specific hospital guidelines are available, adherence to and the use of these is low.

The critical importance of managing blood sugar levels for all patients in ICU, and not just diabetics, was first revealed in 2001 by Greet Van den Berghe in a study at the University Hospital Gasthuisber in Leuven, Belgium, which showed intensive insulin therapy reduced morbidity and mortality among critically ill patients. A key speaker at the Barcelona congress, Van den Berghe has emerged as a world authority in diabetes care, though his initial findings have not been confirmed despite a decade of follow up studies.

However, raising awareness of the critical role of glucose among ICU patients directly inspired more than 2,400 published articles and opened the wide debate on patients, protocols and the appropriate technologies to apply. To set the scene for discussion in Barcelona, Jean-Charles Preiser MD, from Erasme University Hospital in Brussels, Belgium, described the state-of-the-science in his presentation ‘Impact of In-Hospital Dysglycaemia,’ and then expanded the review of in-hospital diabetes technologies by including a wider patient population in a presentation on glucometrics, ‘Measuring Blood Glucose Levels in the Hospital’.

The current consensus is to keep blood glucose as constant as possible for ICU patients to avoid conditions

summarised as dysglycaemia, to avoid hyper- and hypoglycaemia and high glucose variability, he explained.

There is no difference between diabetic and non-diabetic populations because any ICU patient is vulnerable to stress-related hyperglycaemia, which he described as ‘a rapid response to metabolic stress induced by inflammatory mediators, which are sky-high during critical illness whether the patient has experienced a cardiovascular or stroke event, surgery, trauma, infection, or any kind of fever. ‘Clearly controlling glycaemia is a

priority, and we need better tools to have a closer monitoring of blood glucose,’ Dr Preiser said. Current practice calls for blood level checks six times daily in the ICU, ‘… more frequent than it was 10 years before, but we need continuous monitoring, or near-continuous monitoring,’ he said. Resistance to insulin, a reflection of the effects of inflammatory mediators, is changing from hour to hour, he said. ‘So it’s difficult to have a satisfactory insulin infusion rate without taking into account the changes in insulin resistance.’

Dr Preiser pointed out that up to five devices used for continuous monitoring of type I diabetes at home have been adapted for the ICU, and are currently undergoing evaluation and validation ahead of approval for wider use. A first concern is a quality assessment of glucose meters used for monitoring that were originally designed for diabetics and not critically ill patients, he said. Finally, new algorithms need development and testing to adapt insulin rates to maintain normal levels better.

20.12.2011