Article • Cancer of unknown primary

CUP: in search for the smoking gun

Cancer of unknown primary (CUP) can send radiologists on a frustrating scavenger hunt: metastases were detected but the primary cancer is nowhere to be seen. On World Cancer Day (4 February), Professor Alwin Krämer, Head of the Clinical Cooperation Unit Molecular Haematology/Oncology at University Hospital Heidelberg and the German Cancer Research Center, explained strategies for dealing with CUP.

Report: Wolfgang Behrends

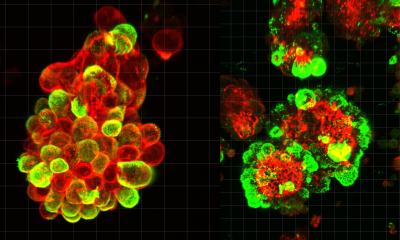

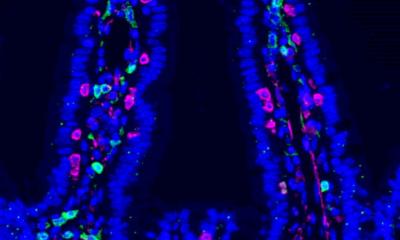

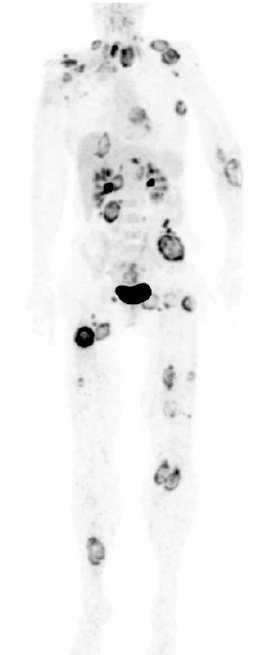

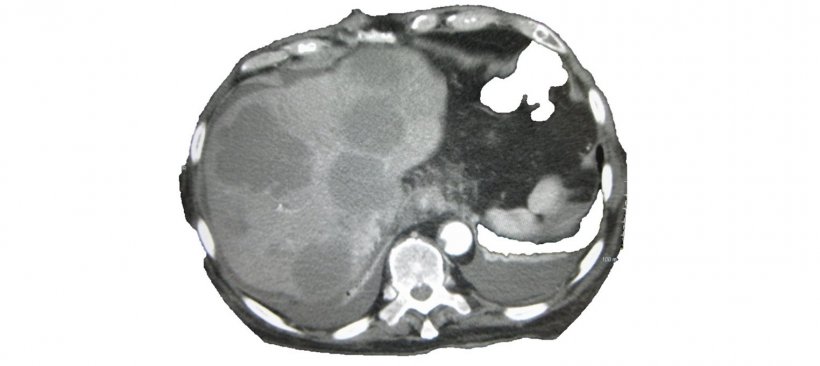

Cancer of unknown primary is a highly heterogeneous disease, says Professor Krämer: “Usually metastases of an epithelial tumour are detected in the lymph nodes, the liver, bones or the brain – but despite comprehensive diagnostic work-up no primary cancer can be identified.” 3 to 4 percent of all malignant tumours and every seventh cancer death are caused by CUP.

The primary tumour is located in only about 20 percent of all CUP patients. In many cases even an autopsy does not yield tangible results. “One possibility might be that the immune system has destroyed the primary tumour but not the metastases. The experts have long been discussing whether CUP is a specific type of cancer where metastases behave differently than in a known primary tumour.”

“There has to be something”

Paradoxically, it is the broad array of diagnostic tools available today that pose a risk for CUP patients. “Very often,” Krämer says, “clinicians try to locate the primary tumour no matter what. This takes time and by the time therapy is initiated the patient’s status has deteriorated.” Thus, the expert recommends treatment onset quickly after the standard diagnostic procedures are completed – even when no primary tumour was identified.

Time is of the essence since in many instances CUP carries a poor prognosis, particularly when little information is available and it thus does not even make sense to speculate about the type of cancer. Prognosis is better when the metastases can be classified. “In only 15 to 20 percent of patients the site or pathology of the metastases indicates the primary tumour type,” Krämer explains and points out that “in women lymph nodes in the axillary region indicate breast cancer. Thus, even when the primary tumour cannot be localised, the patient should receive breast cancer treatment. This will significantly improve prognosis.” The same holds true for women with peritoneal carcinomatosis which indicates ovarian cancer. When the metastases do not provide sufficient clues as to the type of primary cancer unspecific chemotherapy remains the only treatment option. This therapy often combines two active ingredients, one of them a platinum derivative. In these cases, which account for 80 to 85 percent of CUP occurrences, prognosis is very poor and median survival is at approximately 9 months. Thus, the expert summarizes, “on the one hand it is crucial not to lose too much time searching for the primary tumour. But on the other hand subgroups with better prognosis should not be neglected.”

Studies aim to explore new treatment paths

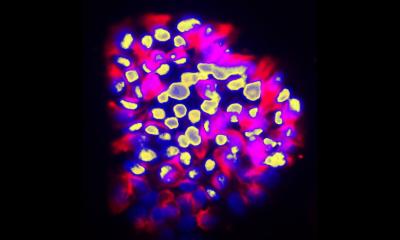

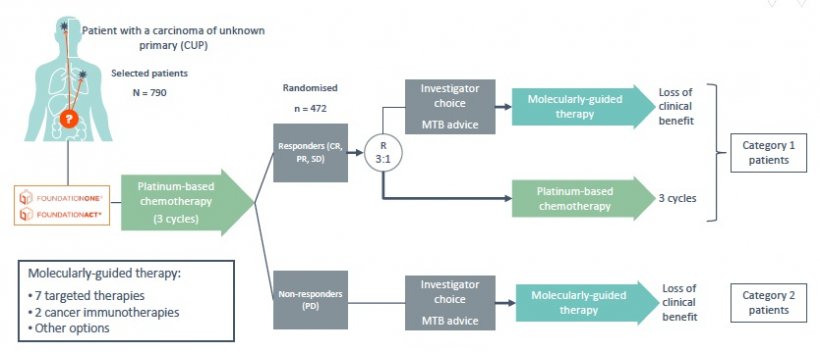

Unlike other types of cancer CUP has not been extensively researched. Now, two large studies aim to close this gap and provide insights and explore new treatments. One of these studies, CUPISCO, focuses on the mutation analysis of tumour genes in order to find targeted therapies. The researchers want to ascertain if mutation specific first-line treatments are superior to unspecific platinum chemotherapy.

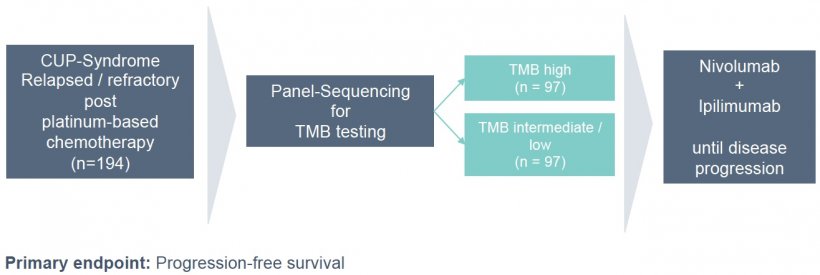

The second study, CheCUP, scheduled to start in mid-2019, looks at CUP patients in whom the metastases did not respond to chemotherapy (second line). So-called immune checkpoint inhibitors will be used to activate the patient’s immune system and attack the metastases in a targeted fashion.

A third approach being discussed is the analysis of gene expression. This might offer insights that can lead to future treatments: “The gene expression profile of tumour tissues is analysed. The profile data are then fed into large data bases to find matches with certain primary tumours. The idea behind this approach is that treatment for a certain type of cancer can be initiated even if the primary tumour itself was not found. So far however research results have been rather sobering: the results of a recently published Japanese study were negative. The results of a randomised French study will be published shortly.”

Profile:

Professor Alwin Krämer is internal medicine specialist with focus on haematology and oncology. He is Head of the Clinical Cooperation Unit Molecular Haematology/Oncology at University Hospital Heidelberg and the German Cancer Research Center. He focuses his research on the causes and consequences of genomic instability. Since 2006, Professor Krämer has been heading the Task Force “Carcinoma of Unknown Primary (CUP)” at the National Center for Tumour Diseases (NCT) at the University of Heidelberg.

11.09.2019