Cancer tumours that fight themselves

Cancer cells producing toxins that destroy tumours – could this be a future treatment for cancer? Researchers at Lund University have achieved good results in tests on both cells and animals. The results have now been presented in the respected scientific journal Cancer Research.

“We have previously discovered that a carbohydrate, xylose, linked to a naphthalene preferentially inhibits growth of tumour cells but not normal cells” says Katrin Mani.

This is something the researchers have been aware of for around 10 years. Since then, they have been working on the mechanism of action of the drug to try to understand why the xylose compound works so well against tumour cells. Two research groups, led by Katrin Mani and Ulf Ellervik, have utilised natural biological processes and tested their ideas in animal experiments, which show up to 97% reduction in tumour growth.

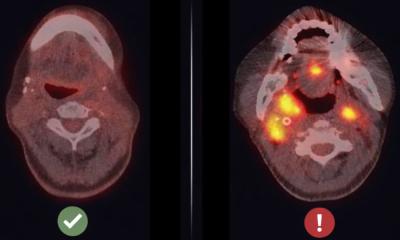

The researchers have found that when the cells are grown together with certain xylose-containing compounds, they begin to produce long carbohydrate chains called glycosaminoglycans (GAG). Different cell types produce different glycosaminoglycans, which are usually transported out of the cell. “Glycosaminoglycans from normal cells are completely inactive. However, glycosaminoglycans from cancer cells are very active. They are quickly taken up by both normal and cancer cells and transported to the cell nuclei where they affect gene transcription and induce an antiproliferative effect, accompanied by apoptosis (cell death). The specific carbohydrate chains from tumour cells are in practice toxins”, says Katrin Mani.

“Around the tumour, where there are lots of cancer cells, a high concentration of the toxin is built up. This means that the tumour produces a toxin that kills itself. When the tumour is gone, no more toxin will be produced”, says Ulf Ellervik. It takes many years to develop an anticancer drug that can be used on patients. However, this is an important step on the way.

“So far all types of tumour we have tested have reacted in the same way and we are very hopeful for the future research results.”

Article:

Attenuation of Tumor Growth by Formation of Antiproliferative Glycosaminoglycans Correlates with Low Acetylation of Histone H3.

Ulrika Nilsson, Richard Johnsson, Lars-Åke Fransson, Ulf Ellervik, Katrin Mani. Cancer Research, 2010, 70, 3771-3779. Published online before print 20 April, 2010, doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4331

30.04.2010